Those who talk about the future are scoundrels. It is the present that matters. To evoke one's posterity is to make a speech to maggots.

- Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Journey to the End of the Night

On a spring afternoon, walking along avenue Mac-Mahon near the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, a friend reminded me of the location's literary history. In Louis-Ferdinand Céline's 1936 novel Death on the Installment Plan, the narrator Bardamu lies on the same street, spotted by police on roller skates before he is transported home in an ambulance following a hallucinatory rage. In frenzied language, he recalls a flight from hecklers in the Bois de Boulogne and a desperate race to the Arc, where he witnessed "a frenzy, a fury" of teeming cars and bloodied figures. Flames rained from the sky. "It was hell," he remarks.

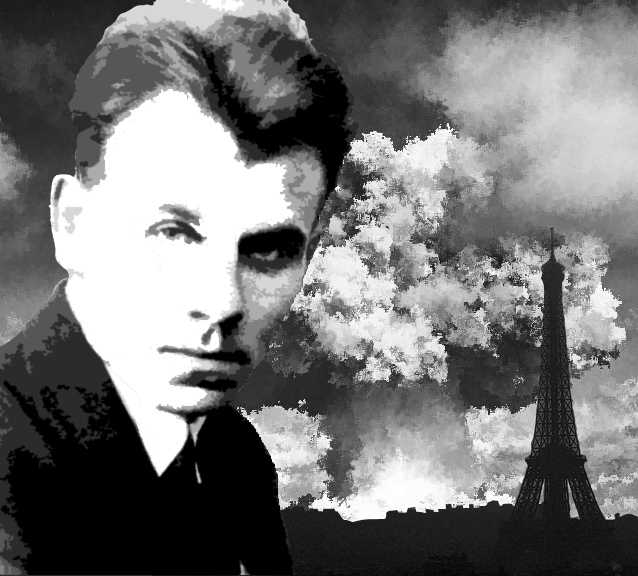

I had read the novel recently, but I could not connect the scene to the moment. On the day of my visit, there was little evidence of bedlam, or any suggestion of life at all beyond the blocks radiating elegant but silent uniformity. In the distance, a group of children mischievously chanted Queen's "We Will Rock You" in uncomprehending accents as we moved further into one of the city's most opulent neighborhoods. The memory of Céline, who both chronicled and despised the subterranean life of Paris, was a bracing corrective to the elegant sterility of the moment. Paris' historical memory is less a palimpsest than a selective erasure. Unlike the fire that destroyed medieval London in the apocalyptic year of 1666, Paris excised and buried its ancient past more methodically, in a brazen program of urban renewal. Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann's city planning of 1852-1870 demolished a large part of the medieval city center, reworking its image into the mannered, iconic elegance that survives as a received, unquestioned ideal of la vie Parisienne. Inevitably, the project has failed to shore up all signs of urban decay. The day before, I passed a mound of dead pigeons, all clearly executed by a human hand, decomposing in front of a stylish kiosk advertising perfume.

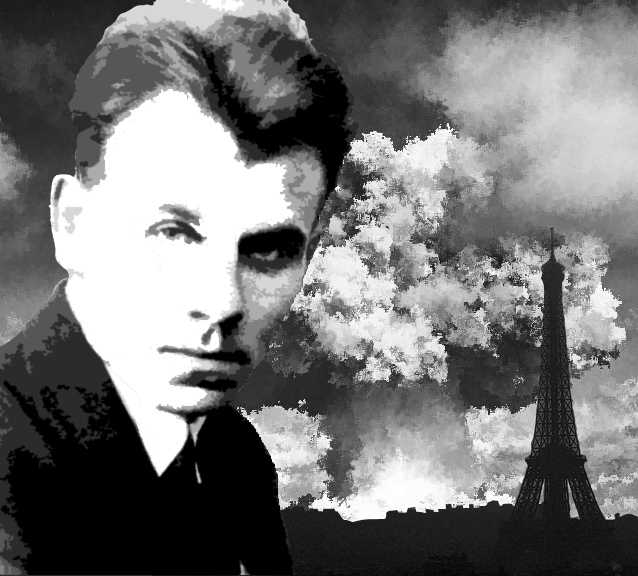

Céline's novels, published between 1932 and his death in 1961, explore an alternate landscape, a project that he imagined as a "métro émotif" or "emotional subway," in which raw experience is mediated by a brilliant observational mind and occasionally leavened by bleak humor. His work is celebrated by counterculture authors, mostly American, that he would not likely have read: Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, and Charles Bukowski, who described Céline's debut The Journey to the End of the Night as the "best book written in the last two thousand years." In France, Michel Houellebecq's misanthropic novels closely mirror Céline's combination of aphoristic observation, black humor and outrageous misadventure. Like Houellebecq, Céline was a brazen provocateur, challenging the conventions of his day; unlike his modern acolyte, a libertarian casually prodding much looser boundaries of respectability, Céline suffered greatly for his missteps and ended his life a cultural pariah.

Céline was born Louis-Ferdinand Destouches in 1894 in the lower-class Paris suburb of Courbevoie; the avenue Mac-Mahon extends vaguely north in its direction from the more prosperous locus of the 17th Arrondissement. Today, Courbevoie is a modern commercial district adjacent to La Défense, a circumscribed financial quarter similar to London's City, where tall buildings contrast uneasily with the lower structures of Baron Haussmann's era. Céline lived his early life in the Passage Choiseul, a roofed shopping area similar to those researched by the philosopher and journalist Walter Benjamin in the Arcades Project. Among its thousands of short notes on modernity and 19th century Paris, he describes the role of the flâneur, a solitary and peripatetic observer of urban life: "The street becomes a dwelling for the flâneur; he is as much at home among the facades of houses as a citizen is in his four walls. To him the shiny, enameled signs of businesses are at least as good a wall ornament as an oil painting is to the bourgeois in his salon."

On the page, Céline serves as a kind of literary flâneur: nomadic, observational, astute and engaged with the quotidian, witnessing life from the literal and figurative vantage of the street. His work reflects his lower middle class roots in its authentic detail and replication of everyday speech, yet it maintains an anxious, discontented impassiveness. Journey to the end of the Night (Voyage a la bout de la nuit), begins on the verge of the First World War, as the narrator Bardamu materializes abruptly, an avatar of the street's energies:

Here's how it started. I'd never said a word. Not one word. It was Arthur Ganate that made me speak up. Arthur was a friend from med school. So we went to the Place Clichy. It was after breakfast. He wants to talk to me. I listen. `Not out here,' he says. `Let's go in.' We go in. And there we were. `This terrace,' he says, `is for jerks.'

Céline then punctuates the action with one of a series of near-aphoristic observations that define his technique:

The people in Paris always look busy, when all they do is roam around from morning to night; it's obvious, because when the weather isn't right for walking around, when it's too cold or too hot, you don't see them anymore; they're all indoors, drinking their cafés crèmes or their beers. And that's the truth. The century of speed! they call it. Where? Great changes! they say. For instance? Nothing has changed. They go on admiring themselves, that's all.

The novel follows a propulsive mixture of bizarre mishaps and observational maxims, its general outline following Céline's own experiences: service and wounding in World War I, his recovery and medical studies, work in colonial Cameroon, and travel to the United States, where he briefly worked as a physician in a Ford plant in Detroit, all expressed with humor and an austere, solipsistic pessimism. During a period of employment at an insane asylum, he observes "I cannot refrain from doubting that there exist any genuine realizations of our deepest character except war and illness, those two infinities of nightmare." Any comedic elements are bittersweet and enigmatic: Bardamu is pursued by a mysterious, affable doppelganger, Léon Robinson, who initially appears to offer a blithely innocent vision of experience, but is finally carried along on the hapless current of misfortune that indiscriminately touches all of the novel's characters. Céline's Journey is often little more than a tragicomic confluence of human entanglements and bitter resignation; implacable forces generate unending chaos.

Céline's misanthropy attracts the reader's sympathy through its introspection and honest complicity with life's accidents; he discouragingly, but honestly, places himself at the center of his hell, which unsurprisingly evokes a wounded cross-current of sentimentality. In later chapters, Bardamu lives and serves the poor as a doctor in the neighborhood of Rancy, often despising his patients' lives while lapsing into sympathetic, nearly maudlin reflection. He obsessively cares for Bébert, a young boy fatally ill with typhus, and is haunted by his death, finally surrendering to bleak acceptance: "I had no luck with Bébert, dead or alive. It seemed to me that there was nothing there for him on earth, not even in Montaigne. Maybe, come to think of it, it's the same for everybody, nothingness." Faced with such a powerful undercurrent of cynicism and grim acquiescence, it is difficult to describe Journey without underplaying its literary charisma. Profoundly readable and entertaining, it was an immediate popular success in France and a failed candidate for the Prix Goncourt, an award that infamously favored academic authors. Céline handled his rejection with predictable outrage, writing in a letter, "except for the War, I know of nothing so horribly unpleasant."

Céline's 1936 follow-up Death on the Installment Plan (Mort à crédit) effectively serves as a prequel to his debut, returning to the adolescent experiences of Bardamu. The lengthy novel employs a more radical narrative technique, fragmenting sentences in imitation of spoken language. Frequent ellipses define verbal rhythms, capturing the aura of a brilliant, if prolix, conversationalist who vaults from impressive verbal summit to summit. Céline follows this general approach more or less regularly throughout his remaining novels, which frequently begin with a digressive autobiographical preamble capturing the improvised thoughts of the moment before returning to a longer ongoing narrative. The "emotional subway" of Céline's fictionalized autobiography rolls on, an epic and verbally inclusive monologue that modulates with the thoughts of the writer, sometimes an outrageous screed interrupted by narrative, other times a more measured description of surrounding events. The language is heightened, climactically charged, as in his descriptions of a stormy passage across the English Channel:

My mother's snarled up in the ropes ... she comes crawling after her vomit ... the little dog is caught in her skirts. We're all tangled up with this brute's wife... They tug at me ferociously... He starts peppering my ass with his boot to get me away from her... He was a regular bruiser... My father tries to mollify him ... he hadn't said two words when the other guy rams him in the breadbasket with his head and sends him sprawling across the winch... And that wasn't the end of it!

The dark, expansive observations of Journey are now frequently rendered as pure effects; Céline writes in the service of brute impact and immediacy, but remains a storyteller of enormous energy. In its cadences of pure, elliptical speech, the novel brims with artless spontaneity, a pure and unpretentious entertainment. The story is classically picaresque. Bardamu endures a hellish home life under a troubled father and a hard-working mother who quixotically attempts to earn a living selling lace to wealthy Parisians. He moves from job to unsuccessful job, tries an education in England, and finally works for Courtial, an eccentric inventor with a utopian vision of pastoral life. All of Céline's characters expend unusual vigor against inevitable defeat, yet Courtial is the novel's most tragicomic spirit. He finally attempts to enhance vegetable growth with "radiotellurism," an infusion of magnetic energy, founding a commune around the project, but neither his vegetables nor utopian dreams reach fruition.

Céline's next missteps were like Courtial's fictitious inventions, tragically misguided and tainted by pseudo-intellectualism. His general misanthropy fused dangerously with a contemporary current of anti-Semitism, and between 1937 and 1941, he composed three anti-Jewish pamphlets: Bagatelles pour un massacre (Trifles for a Massacre) (1937), L'École des cadavres (School of Corpses) (1938) and Les Beaux draps (The Fine Mess) (1941). Céline's racist attitudes are unmistakable, but his connection to the distinct tenets of Nazi philosophy is uncertain. He maintained tangential relationships to collaborators Pierre Constantini and Henri Poulain, who expressed admiration for his pamphlets, but Céline's apocalyptic laments and hallucinatory denunciations of Western culture were less expressions of specific dogma than explosions of a broader nihilism.

Fleeing France as the Vichy regime fell, Céline, his wife Lucette (cast as Lili in his novels), cat Bébert and the actor Robert Le Vigan, travelled to Sigmaringen in Germany, where he worked as a physician to a retreating colony of French collaborationists that included the Vichy Chief of State, Phillipe Pétain. Ultimately, Céline, Lucette and Bébert reached Denmark in 1945, where they remained until 1950. In his absence from France, Céline had been sentenced to one year imprisonment, but had also been the victim of a more damaging, extra-judicial sentence; his property was largely plundered, he was marked for death by avenging members of the resistance movement, and his publisher was shot to death on the streets of Paris. He returned to France under amnesty in 1951 and lived in relative exile with his wife, Bébert, and a larger menagerie of pets in the suburb of Meudon.

In a 1960 Paris Review interview, Céline remarked: "I've become a chronicler, a tragic chronicler. Most writers look for tragedy but they don't find it...hell, it's not every day you get a chance to ring up the gods." Céline's final sequence of novels, from Fable for Another Time, through the trilogy Castle to Castle, North, and Rigadoon, serves as an extended narrative of his life during the war, both in its literal events and also as a record of his increasingly agitated subjective state. Bardamu is now fully Céline, although the irreducible name Destouches occasionally resurfaces, as if by accident. The final trilogy uncomfortably fuses past and present; Céline muses bitterly, often in incomprehensibly personal terms, on his informal death sentence, his cultural exile, his loss of property, and his general state of despair. His technique remains fixed since the apotheosis of Death of the Installment Plan, but he proceeds with increasing disregard for his audience. Already implacable and distant as a narrator, Céline retreats further and further into a world of unmediated personal obsessions.

Readers will question whether the anti-Semitism of Céline's pamphlets taints his work as a whole. Milton Hindus, a Jewish critic who visited Céline during his Danish exile, forgivingly remarked in a 1954 review of Guignol's Band, "Americans might profitably learn from the French their ability to separate a man from his work." Hindus may have overestimated France's capacity for forgiveness, but it is a worthy exercise. In Céline's novels, his most infamous political ideas and prejudices never surface directly; their outré, outlaw qualities come from more predictable quarters, such as their rage, chaos, indignation, and mystification at life, literary sentiments that have long since become quaintly de rigueur. Inevitably, a lingering discomfort surrounds his work, similar to the infamy shared with the work of another notable exile of Meudon, Richard Wagner, whose operas directly resist anti-Semitic interpretations in spite of their author's personal ideals. With sensitive reading, but perhaps not absolute forgiveness, both artists' works can live with deserved independence from the polemical hatred of their eras.

Céline died on July 1, 1961 from the lingering effects of a head wound sustained as a cavalry officer in World War I. His widow, who feared a violent public reaction, initially kept the news secret. Ernest Hemingway, a chronicler of the same conflicts, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on the same date, a self-proclaimed man of action counterpoised in death against Céline's genuine victim of war. Céline had little doubt that his work offered the most authentic expression of his era's tragedies, and imagined that literature itself had died with the ideals of the century. In his final work, Rigadoon, he offers an unrepentant, weary reflection on his ideals and relevance, a fictional interchange with a troublesome interviewer. The journalist opens the dialog:

"Maître, oh dear Maître! Your opinion! Two words!"

"Hell's bells, I haven't got any!"

"Oh, but you have, Maître."

"About what, dammit?"

"Our new literature!"

"That obscene antique? Zounds, it doesn't exist! Fetal stammering, that's what it is!"

The same writer dedicated his final novel "To the Animals," a more benign order that he hoped would inherit the earth.

© 2007 by Sten Johnson.