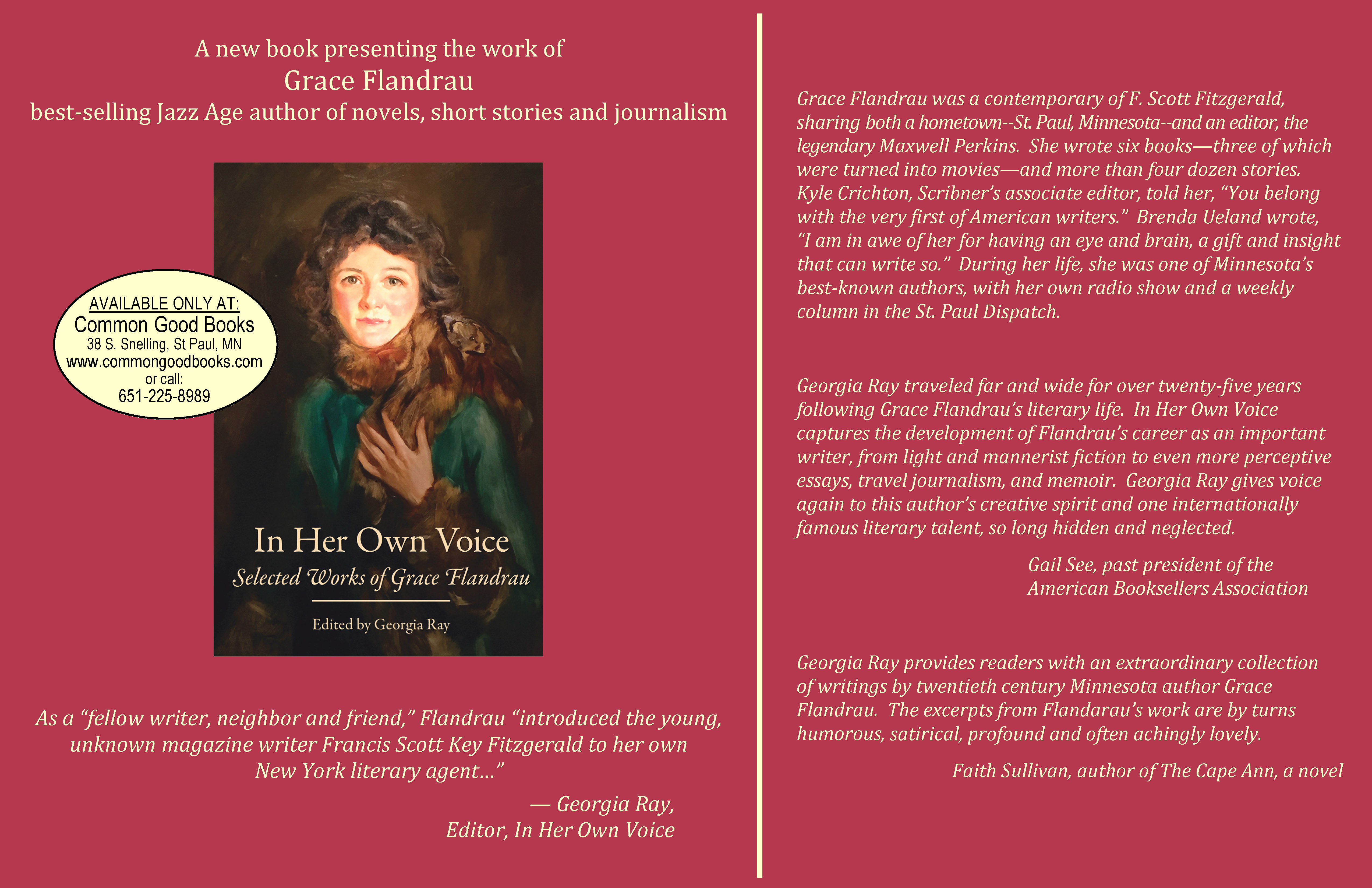

F. Scott Fitzgerald grew up in St. Paul but left at the earliest opportunity for richer cities-richer in both culture and sheer wealth-like New York and Paris. Grace Flandrau also grew up in St. Paul and wrote about the rich, but she remained here most of her life, and her rich were the steel kings and railroad barons of Summit Avenue. Yet her novel Being Respectable became a best-seller and was made into a movie, and her short fiction was published in top magazines like McClure's, The Saturday Evening Post, and Harper's Monthly. Her celebrity in the 1920s and `30s was considerable and made her a bright star in the constellation of Minnesota novelists of that era: Fitzgerald and O.E. Rolvaag, Sinclair Lewis and Maud Hart Lovelace. Why, then, is she a "lost writer"? How did she disappear so completely from literary memory?

Flandrau was born Grace Corrin Hodgson in 1886, in a house at 518 Dayton that was about a block from the house where Fitzgerald was born. She was about ten years his senior and it is plausible, even likely, that young Grace, skipping rope or playing hopscotch, was passed by young Scott being wheeled in his perambulator. The illegitimate daughter of a businessman in mortgage banking, Grace came from a family that was well connected, if not always well off, and she spent part of her childhood in Paris and New York. Her marriage in 1909 to Blair Flandrau, the younger son of an old money family, solidified her position in the leisure class and gave her ample time to write-in Mexico, where she went with Blair to run his coffee plantation, and later when they had returned to St. Paul, the plantation given up in the upheavals of the Mexican Revolution. Though not particularly unconventional, Flandrau's independent character and disdain of social orthodoxy made her a bit of a flapper, like her friend Brenda Ueland. After World War I she spent six months alone in Paris reuniting war orphans with their families.

Flandrau's major novels all take place in St. Paul and are all satires of high class society, portrayed unerringly as vapid, imprisoning, and even destructive. In Cousin Julia (1917) the title character is an ambitious matriarch who recruits poorer but more sophisticated cousins from back East to help her daughters win a coveted position in the best society:

To become a personage, a great lady of the city where she was born and that she had seen grow from a village to the large and important capital, had become her purpose. She intended her daughters to make brilliant matches, to take their place socially with and above the handful of people who had always been considered, since the early days, the aristocracy of the town. She had systematically climbed by all the approved methods, charities, church work, clubs, lectures, musicales, and lastly and most importantly, her daughters.

In Being Respectable (1923), Darius Carpenter's family is already at the top of the social milieu in Columbia (St. Paul). Charles, his son, has made an advantageous marriage to Suzanne, a pedigreed girl from the East, but he quickly finds he is more attracted to his old flame, the beautiful but fortuneless Valeria Winship. Louisa, the older daughter, fights tooth and nail to keep in the "smart set", while her husband Phil Denby strikes up a friendship with a working class girl and her mother-he feels more comfortable slumming in their "bungalette" than on Summit Avenue. Meanwhile Deborah, the younger daughter and nominal heroine of the book, mocks the self-important St. Paul aristocracy she has been brought up in and gads about with Steven, an idealistic journalist fond of getting drunk. As in John Galsworthy's earlier novel, A Man of Property, Being Respectable shows a wealthy and staunchly conservative mercantile family toppling under the ephemeral forces of beauty and love. Charles, though hidebound and simplistic, is the most revealing character. After an evening with Valeria:

"I was just alive," he thought, bewildered. And what harm had it done anybody? Really what harm? He had not given Valeria anything he could not have given Suzanne.

The Carpenters, like the Forsytes, regroup and grimly soldier on after Valeria and Steven (like Irene and Bosinney) stage a mutual betrayal. As Flandrau observed in an interview, "The spectacle of human life is very amusing and very sad."

But these years were probably happy ones for Grace-or at least flattering. She and her brother-in-law Charles Flandrau, also a noted writer, lived at the center of the St. Paul literary scene. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald stopped by Blair and Grace's brownstone at 548 Portland whenever they were in town, and Edith Wharton wrote a personal letter to Grace: "May an unknown reader write you of her very great admiration for your book Being Respectable? It's too full of good things to be adequately praised in a few words."

Yet for all the praise, the sales, the movie, Being Respectable does not stand up today next to something like The Great Gatsby, or Babbitt. It is, to be sure, a thinking novel, and is "full of good things" intellectually. But points of view change quickly, scenes are seldom vividly realized, and the narrative progresses in jumps and starts. Valeria is a defining character but we never know what she thinks, and she only has two or three lines in the whole book. Perhaps the crux of the problem is that Flandrau tried to make her characters too realistic-they do not beautifully stand for one idea but agonizingly dither between a dozen. As Deborah reflects late in the novel: "The trouble with the people she knew was that they muddled. Things were not clear to them-even the little things that some straight thinking might have made clear." This may explain why, nearly a century after her work began being published, all of Flandrau's novels are out of print and no longer read.

No longer read-but far from unreadable. Flandrau's restless, questing prose is smart, and occasionally beautiful. And St. Paul readers will discover interesting scenes at locales like Summit Avenue, Hazel Park and the State Fair. My own neighborhood is described in Entranced (1924), about an ambitious lawyer, Dick Malory, who is ashamed of his humble origins and divorcé father:

The Dodd Road, where Malory had his farm, is on the high bluffs above the Mississippi, just across the river from the main part of the city. The region is called the West Side, although just here it is south. It was, at that time, still a lovely farming country, and yet not more than an hour's walk from the center of town.

Entranced was not as successful as Being Respectable, and Flandrau began to focus on journalism. She turned out several pamphlets on early Minnesota history for the Great Northern railroad, and a trip to Africa in 1927 provided fruitful material for a travel book (Then I Saw the Congo) as well as a collection of stories (Under the Sun). As a travel writer, Flandrau was ahead of her time, exploring her exotic locale with an objective, humanistic standpoint, and challenging the notion that Europeans were the superior race.

After the stock market crash of 1929 Blair and Grace moved to Paris for several years, where they could live in style with limited means. Grace wrote one more novel, Indeed This Flesh (1934), based on the life of her father, but short fiction, speaking appearances, and a radio show on KSTP took up most of her time. She had planned an autobiographical novel in the vein of Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward Angel, but as she confided to her editor, Max Perkins at Scribner's, she had "a feeling of being doomed" and that "my heart is squeezed with a kind of despair." She battled depression much of her adult life.

Blair Flandrau, an alcoholic, died in 1939, and Grace wrote little after the early `40s, splitting her time between homes in St. Paul, Connecticut and Tuscon (Charles Flandrau died a few months before his brother, and she had inherited both of their estates). On her death in 1971, most of her fortune went to charities, including a bequest to the University of Arizona in Tuscon; with the money the university built the Grace Hodgson Flandrau Planetarium, still in operation. Astronomy buffs, respectable or otherwise, probably do not think its spectacle of stars amusingly funny or amusingly sad, but they might wonder, from time to time, whether some of them have gone missing.

© 2008 by Joel Van Valin.