Western literature since Beowulf could be seen as an endless story of influence-the exercise of, and resistance to. Mesmerism (aka animal magnetism, hypnotism), in its practice of total subjugation, is the ultimate form of influence. And the ultimate influence is death.

Twentieth Century literary references to mesmerism / hypnotism are scattered and superficial, referring mostly to the visually arresting qualities of things like arm hair, neon lights, mounted police, an approaching boat, or a woman's lips pronouncing the letter B (actual examples). At least two modern exceptions are Madison Smart Bell's Dr. Sleep and Murakami's Coin Locker Babies, where hypnotism is connected to homicide, though thematically tangential. The stage version is almost always preceded by the word "comedy."

In the 19th Century, however, mesmerism, with its invisible vital fluids flowing between bodies and souls, was a central matter of human existence. It was a connecting cable from science to the supernatural, conflated with religion and theories of electro-magnetism. The telegraph (which eventually led to the cell phone) was originally thought to be a form of mesmerism-instantaneous influence at a distance. Edison originally invented the phonograph as an electrical device to preserve one's last words. He believed electricity formed a link with the spirit world, and some of his first microphones (eventually used in telephones) were intended to amplify the voices of departed souls. In medicine, mesmerism was the form of anesthesia, preferred even after chemical anesthesia was invented. It was life itself. And where you have life, you have death, and sometimes the motive to hurry it along.

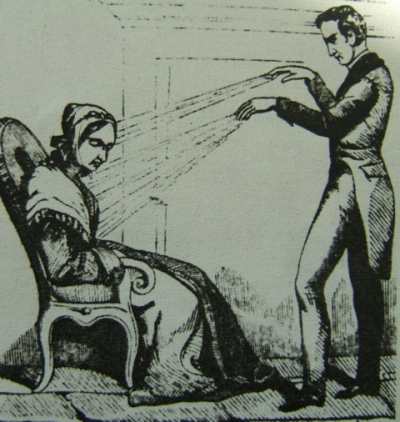

When Franz Anton Mesmer first put magnetic-mesmeric-hypnotic influence on the map at his lucrative gig in Paris (1770s), subjects went berserk and their trance was termed a "crisis." People spontaneously laughed, cried, hooted, barked, chirped, meowed and generally behaved like an unsupervised study hall. By the early 1800s, mesmeric response became as serious as a sealed coffin.

Besides appearing "as cold as death itself," subjects began to see other people as literally so. A year after Mesmer died, a well-known German trance medium predicted the death "in an uncommon manner" of a high-ranking person identified in Blackwood's Magazine only as "S.M.," and specified a time in April, 1816. A second medium moved the date to October. The effect of all this background buzz on when S.M. was going to fall off the perch is not known, but "those who are acquainted with the event do not require to be told," and "many bets were won and lost." S.M. was apparently not among the winners.

Balzac, who personally knew many of the leading mesmerists of his day, put more action into the I-can-see-you-dead theme in Ursule Mirouët (1822). Ursule is visited in a dream by her dead godfather, a former skeptic convinced by a demonstration of mesmerism. In this dream he reveals a secret plot by relatives to steal her inheritance, and predicts the death of one of them if they don't desist.

In 1827 Dr. Foissac, a French physician, hypnotized an epileptic who predicted his own seizures. According to an article by Thomas ("holds him with his glittering eye") de Quincey, Foissac's patient predicted that he would murder his own family. It might have been that certain something sensed by animals (animal magnetism) that spooked the hypnotist's horse into pulling a buggy over his subject and killing him. The prediction was correct in an Oedipal sort of way. The subject was part of his own family and did kill himself by stepping in front of the horse.

In a century where premature burial was common (evidenced by bells rigged above ground in case the stiff came alive, and scratch marks inside many coffins without them), there would naturally be a macabre interest in a technique like mesmerism that seemed to blur the life-death event horizon. In an 1817 report, a Mrs. Zimmerman in Bielefeld, Germany was dying of tuberculosis. Her husband kept her in a mesmerized state for 24 days, but she "shewed no symptoms of amendment." However, she would not die either. "Life and death struggled together." She appeared to pass away whenever her husband left the room, but when he returned, so did she. Finally the husband left and didn't come back. Neither did his wife.

In Hawthorne's House of the Seven Gables (1851), when young Gervayse Pyncheon runs to climb on his grandfather's knee, he discovers to his horror that grandpa has suddenly become a corpse, the result of a wizard's death curse from years before. George du Maurier's evil hypnotist, Svengali, from his novel Trilby (1894), sits in the audience during Trilby's final performance, and for a long time no one realizes that he is dead as a rock. In "Mesmeric Revelation" (1850) the magnetizer ("P.") has a philosophic dialogue with a subject he thinks is in a trance, but when he wakes him up, realizes he's been dead all along. A man appears to be a corpse in "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" (1845), but a mesmerist ("P." again) keeps him alive in a magnetic somnolency for 7 months. When Valdemar speaks, he says, "I am dead." When the mesmerist finally brings the subject out of his trance, he quickly turns into "a nearly liquid mass of loathsome...detestable putridity."

After the initial mosh pit of Mesmer's 1770s thrill show, and the life-death osmosis of the years that followed, both real and fictional mesmerists settled down to the business of using their talents to cause death itself.

Balzac's serial killer, The Centenarian (1822), uses mesmeric influence to immobilize his victims for the final snuff, especially women. Tullius arrives at the Centenarian's house just in time to see the killer carrying Marianine, in a catatonic spell, down to the chamber of death, where, like a vampire, he needs her vital magnetic fluid to keep living.

In a medical demonstration in 1891, a hypnotized man was told he could not breathe. Respiration stopped for three minutes and it was "believed death could be caused unless the spell was removed," which it was just in time. The New York Times reported an experiment where a hypnotized subject obeyed the command to put arsenic in the food of a friend. In another experiment a girl in a trance pointed a revolver at her mother. The hypnotist told her it was loaded and to pull the trigger. She did. Within a year of these demonstrations, a Belgian "professor" hypnotized a man onstage and told him to kill his father, whereupon he "enjoyed killing him in cold blood," presumably with a fake weapon. Not long after these and similar stage demonstrations, the theme of murdering a family member appeared in The Mesmerist (1890), by Ernest Oliphant, where Allan Campbell is hypnotized to kill his brother, Hugh, hoping he will in turn commit suicide out of grief, at which point Hugh's fortune would go to his sister-who just happens to be the hypnotist's wife.

Proximity of the mesmerist to the subject became one of the central themes of mesmeric concern, and many experiments were conducted to see how far away the hypnotist could be and still exercise power. This went from one-on-one clairvoyant commands from an adjoining room, to influence by letter, phone, and eventually mass control by radio and beyond. While in a trance, Bedloe, in Poe's "Tale of the Ragged Mountains" (1844), walks alone in the wilderness, and stumbles upon a non-existent location, where he sees an imaginary officer killed. While still in a waking sleep, he himself is "killed" by a poisoned arrow. He tells this experience to his mesmerist, Dr. Templeton, who happened to be writing an account of the officer's death at the same time Bedloe was witnessing it. A week later Bedloe dies, not from a poisonous arrow, but a poisonous leech inadvertently applied by the overly curious-but underly cautious-doctor.

Thomas Maule, one of several mesmerists in House of the Seven Gables, hypnotizes the daughter of a shady landowner and says, "She is mine!" Then he telepathically commands her to a fatal end.

Human beings aren't the only ones felled by the hypno-zap. At a party given by Chateaubriand in 1802, a stage hypnotist named Abbé José-Custodio de Faria tried to kill a canary with his mind, but failed. More successful was the fictional stage magician Brunoni, in Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford (1851), whose "will seemed of deadly force." He kills a canary with only a word and possibly a dog named Carlo. Coincidentally, the dog's name is identical to that of the dog abused by the homicidal mesmerist in "John Barrington Cowles," by Arthur Conan Doyle. In that story Miss Northcott, a beautiful woman with hypnotic powers and a shameful, unnamed secret uses those powers to cause the deaths of three young men, after they find out what her secret is. Her statement that "every time a man misbehaved...he were lashed with a whip until he fainted" might be a clue. But mesmeric death can be a two-way street, as Doyle showed in The Parasite (1895). In this case the evil mesmerist, Miss Penclosa, almost gets her subject to throw acid in his fiancé's face. Fortunately for the fiancé, this command at a distance is short-circuited when Penclosa dies of hypnotic over-exertion.

By the end of the 19th Century, fictional hypno-murder gave way to the real thing. A Frenchman in Algeria, Henri Chambige, mesmerized his girlfriend, Madeleine Grille, presumably to prevent her resisting, then shot her in the head. In Hungary someone named Neukor hypnotized a young woman at a séance, and for entertainment purposes told her she had consumption. She shrieked and immediately fell dead. Laws and prohibitions worldwide against these kinds of stunts did not help Spurgeon Young, the professional hypnotic subject in New York, who died of "nervous exhaustion from hypnotic practices" in 1897. In a possible copycat case, a Russian with control issues, Ivan Benedich, repeatedly hypnotized the woman whose family would not let him marry. To get revenge on the family, he put her under and told her she had consumption. She began to show symptoms, but the family still said no. So Benedich let her die of a disease that was nothing more than a suggestion.

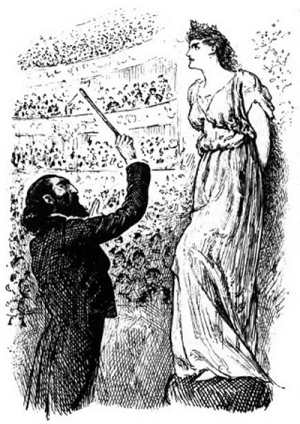

Eventually, every form of mesmeric murder, real or imagined, in life or fiction, had seemingly been tried. But Henry James (who created Dr. Tarrant, the hypnotic charlatan in The Bostonians) came up with a new twist, which he gave away to George du Maurier, who used it in Trilby, one of the most popular novels of the 19th Century. Early in the story, Trilby is warned about those no-good mesmerists: "They get you into their power, and make you...murder, steal...anything! And kill yourself...when they've done with you!" But Trilby is a teenager and we all know how they respond to warnings. So the evil hypnotist, Svengali, turns her into a virtuoso vocalist by working her 8 hours a day by hypnotic suggestion until her relatives say, "our Trilby [is] dead." In the concluding scene she looks at the deceased Svengali's photograph, whose eyes are still able to hypnotize her, and sings at her all-time best. Then she herself promptly dies, her vital essence sucked away by the mere representation of a hypnotist no longer among the living.

Killing someone through hypnosis is one thing. Getting away with it is another. One of the more ingenious devices of real-life Svengalis was to hypnotize someone else to make the hit and take the risk of getting caught. In the famous Affair of Gouffé's Trunk in 1891, 20,000 people came to the Paris morgue (the same morgue Svengali used to frighten and control Trilby) to see the trunk where the body of court bailiff Alexandre-Toussaint Gouffé was found. The young and beautiful Gabrielle Bompard used sex to lure Gouffé to a hotel room. Her middle-aged boyfriend, Michel Eyraud, then jumped out from behind a curtain and strangled him for his pocket cash. Bompard claimed she was given a post hypnotic suggestion by Eyraud to participate in the crime. Eyraud claimed he was "hypnotized" by Bompard's "insatiable appetites." The court's reaction? She got 20 years, he got the guillotine.

In Winfield, Kansas, as Thomas Patton rode his horse down the road, Thomas McDonald, hiding in a tree, shot him dead. But the murder was not McDonald's idea. He had been programmed by the hypnotist Anderson Grey. A neighbor had transferred some land into Grey's temporary possession so his wife wouldn't get it in a divorce. Grey decided he wasn't going to give it back. Patton was the only witness to this secret deal, so naturally he had to die. At first Grey tried to hypnotize Patton to kill his own cousin (who was a better shot), hoping Patton would be killed in return. That failed. So he recruited Thomas McDonald, who had just gotten married. Grey told the groom under hypnosis that Patton had the hots for his bride, which he hoped would give McDonald a motive to kill him, which he did. The scheme fell apart and the hypnotist was found guilty of murder. The trigger man was set free to rejoin his bride.

The same year that Trilby became a best-seller and a social phenomenon similar to the hoola-hoop, a spoiled rich kid named Harry Hayward became known as "the Minneapolis Svengali" for hypnotizing a janitor, Claux Blixt, to murder a dressmaker, Katherine Ging. The motive was to collect two life insurance policies he'd talked Miss Ging into taking out, with the hypnotist as beneficiary. After repeatedly putting the janitor into a trance, Hayward told him to pick up Miss Ging by horse and buggy on Hennepin Avenue near downtown. Following Haywood's hypnotic suggestion, the janitor drove her to Lake Calhoun, shot her in the head, and dumped her body on the road. Unlike the Kansas case of ten years earlier, where the shooter walked, in this case the janitor in a trance got life in prison. Haywood, whose only stated regret was not killing Blixt afterward as originally planned, went to the scaffold, where he recited a couple of stanzas by Dryden, reportedly with a Svengalian sneer. It's not known whether the sneer remained after they pulled the trap door.

You can say to the evil mesmerist, male or female, "you aren't from around here, are you?" In fiction, at least, they are foreigners and outcasts. (In real life, the homicidal ones are not much different from you and me.) Doyle's Madame Penclosa is from Trinidad; Svengali is a Jew from Germany (his deadly photo taken in "the mysterious East"). Balzac's Centenarian has no papers, was born centuries ago, lived in China, India and the New World. He's not even present where he is, but moves about in a "disembodied manner." Count Fosco in Wilkie Collins's Woman in White (1860) is a traveling magician from a foreign country, who manipulates a family with the sinister motive of stealing an inheritance. Two people die in the process. Matthew Maule in House of the Seven Gables is a social outcast and has a shaky claim on the very land on which he lives. His grandson, Thomas, doesn't go to church and holds "heretical tenets," which in his day meant total exclusion. Earlier in the story, Holgrave (note the name), the daguerreotypist and amateur mesmerist, breezes in from nowhere, and Westervelt in The Blithedale Romance is a nomad who presents himself as a foreigner in Oriental robes. Coverdale, the narrator, calls mesmerists "goblins of degraded death...outcasts, mere refuse-stuff."

They're physically different, too. The Centenarian is a giant, as is Svengali. Miss Penclosa is a "creature with a crutch...a deformed woman." Miss Northcott (in Doyle's "John Barrington Cowles") stands out with her "extreme beauty" of the "I have never seen such" variety, and Professor Westervelt, according to Coverdale, moves Centenarian-style, like an apparition, and comes off as "less appropriate" than "the savage man of antiquity." His eyes expose "something that ought not to be left prominent."

The same mouths that issue lethal suggestions also form into mocking laughs and sneers once they're carried out. Sophie de Ravendsi, the man-killer who lays an enchantment trip on Tullius in The Centenarian, dumps him with "flippancy" and a "laugh." The Centenarian himself has "a smile worthy of Satan." When Doyle's Miss Penclosa gets her hooks into Gilroy-his fiancé notwithstanding-she "only smile[s] out of amusement." And when Miss Northcott hears that her hypnotic effect upon Archibald Reeves caused him to die, she simply laughs.

What exactly is the hypnotic trick that makes someone do your bidding, like run over a cliff, throw acid in someone's face or shoot their neighbor? As with Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, you don't need to hold them with your skinny hand. Just the eye will do ("the Mariner hath his way"). Svengali's "big eyes" are "full of stern command." Light (a form of electro-magnetism) plays a part: eyes of fire, eyes with an infernal and blinding light, his flaming eyes, a thread of light from his hollow eyes, etc. When Balzac's Centenarian meets his prize victim, he focuses on her "the full beam of his eye." Doyle's Penclosa has eyes that follow people with "serene confidence" until they fall under her fatal control. His Miss Northcott has a gaze so powerful it overrides and disrupts the powers of a performing hypnotist, driving him from the stage. Hawthorne's Thomas Maule, "by the power of his eye...could draw people into his own mind" before killing them.

The eyes capture attention, but it's the voice that delivers the goods. The evil Beringheld-Sculdans in The Centurian has a voice like "the sound that issues from under an aqueduct," and when he insinuates it into the ear of Marianine, she's as good as gone. The voice of Balzac's mesmerist in Ursule Mirouët "comes from the depths of his being...charged with some magnetic fluid [and] penetrates the hearer at every pore." And Trilby, under the voiced commands of Svengali, becomes herself "the apotheosis of voice and virtuosity." Then she dies from hypnotic suggestion.

By 1899 Nietzsche and D'Annunzio had extended mesmeric power into philosophies of the primacy of human will. The rapidly-evolving radios, microphones, telephones and other forms of influence at a distance, substantiated earlier theories of electro-magnetic command and response. There was a time in the not-too-distant past when the only way to hear a person's words was to be close enough to hear them when they were spoken. Eventually, however, the voice of power, like the commands of Balzac's Centenarian killer, became disembodied, electrically amplified, and extended to mobilize huge masses, and stage the two Great Wars, resulting in 90 million deaths. Great gain was hoped for by many, and made by a few.

But now you can let all of that drift away. Sit back, push "Power" and relax. Let the screen draw you in. Deeper and deeper. Don't worry, none of the above could ever happen again.

© 2009 by John-Ivan Palmer.