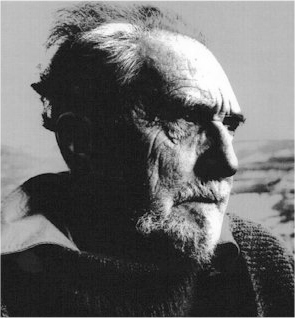

Ezra Pound, the Writing Teacher

"One Can't Criticize and Be Tactful All at Once"

by Bob Blaisdell

Ah well, you may have got a worse overhauling than you wanted, but one can't criticize and be tactful all at once.

-Pound to Iris Barry, 1916

This first page of book two is bad. I mean it is just translation of words, without your imagining the scene and event enough, and without attending to the English idiom.

-Pound to W.H.D. Rouse, on translating The Odyssey, 1935

I confess I'm no student of Pound's poetry and that The Cantos have never hooked me. I like his "Imagistic" verses and I love his translations from the 1910s. I admit that I don't know whether he became crazy or not, but I would prefer to believe he did. That he was a great writing teacher to a variety of writers, on the other hand, seems indisputable-and one with which he himself would not have argued:

Yeats used to say I was trying to provide a portable substitute for the British Museum. I think Instigations [a book of Pound's reviews and essays] WAS the university for people who were getting educated in 1920.

Let's start with a few of what I would call his maxims before we look at his tutorials with poets Iris Barry and Mary Barnard. Pound's maxims still seem fresh because he was figuring them out, or weighing them again-perhaps he would say he was simply recognizing them-as he wrote them.

Laws do not begin with the man who puts them in print; whatever "laws of imagisme" are good, have been good for some time.

A classic is classic not because it conforms to certain structural rules, or fits certain definitions (of which its author had quite probably never heard). It is classic because of a certain eternal and irrepressible freshness.

When Harriet Monroe, in Chicago with her magazine Poetry, resisted him or his suggestions, he felt called upon to educate her:

A poem is supposed to present the truth of passion, not the casuistical decision of a committee of philosophers.

Pound's most lively, sharpest statements on the art of poetry erupted in his letter-writing, and what follows, in another pedagogic letter to Monroe, is a lava-flood of maxims:

Poetry must be as well written as prose. Its language must be a fine language, departing in no way from speech save by a heightened intensity (i.e. simplicity). There must be no book words, no periphrases, no inversions. It must be as simple as De Maupassant's best prose, and as hard as Stendhal's.

There must be no interjections. No words flying off to nothing. Granted one can't get perfection every shot, this must be one's INTENTION....

There must be no cliches, set phrases, stereotyped journalese. The only escape from such is by precision, a result of concentrated attention to what is writing. The rest of a writer is his ability for such concentration AND for his power to stay concentrated till he gets to the end of his poem, whether it is two lines or two hundred.

Objectivity and again objectivity, and expression: no hindside-beforeness, no straddled adjectives (as "addled mosses dank"), no Tennysonianness of speech; nothing-nothing that you couldn't, in some circumstance, in the stress of some emotion, actually say. Every literaryism, every book word, fritters away a scrap of the reader's patience, a scrap of his sense of your sincerity. When one really feels and thinks, one stammers with simple speech; it is only in the flurry, the shallow frothy excitement of writing, or the inebriety of a metre, that one falls into the easy-oh, how easy!-speech of books and poems that one has read.

Language is made out of concrete things. General expressions in non-concrete terms are a laziness; they are talk, not art, not creation. They are the reaction of things on the writer, not a creative act by the writer.

In a review of Robert Frost's verse, he boiled down the artistic impulse into two elements: "There are only two passions in art; there are only love and hate-with endless modifications." But besides the necessary passion, he later described the need for technical know-how:

Good writers are those who keep the language efficient. That is to say, keep it accurate, keep it clear.

The best work probably does pour forth, but it does so AFTER the use of the medium has become "second nature," the writer need no more think about EVERY DETAIL, than Tilden needs to think about the position of every muscle in every stroke of his tennis....

Especially as the years passed, Pound's poetry was not always immediately fathomable, but from the start he was much more leery of symbols than some of his contemporaries:

There's a dictionary of symbols, but I think it immoral. I mean that I think a superficial acquaintance with the sort of shallow, conventional, or attributed meaning of a lot of symbols weakens-damnably, the power of receiving an energized symbol. I mean a symbol appearing in a vision has a certain richness & power of energizing joy-whereas if the supposed meaning of a symbol is familiar it has no more force, or interest of power of suggestion than any other word, or than a synonym in some other language.

Symbols-I believe that the proper and perfect symbol is the natural object, that if a man use "symbols" he must so use them that their symbolic function does not obtrude; so that a sense, and the poetic quality of the passage, is not lost to those who do not understand the symbol as such, to whom, for instance, a hawk is a hawk.

Never shy of educating his elders, he declared to one of his former college professors that art teaches: "A revelation is always didactic. Only the aesthetes since 1880 have pretended the contrary, and they aren't a very sturdy lot."

Though he didn't turn down anybody who called himself a writer, he preferred (he told his unwilling pupil Harriet Monroe) teaching the young: "I don't lay as much stock by teachin' the elder generation as by teachin' the risin', and if one gang dies without learnin' there is always the next."

When Marianne Moore, a then-unknown writer, sent her poems to him, he was surprised by how impressed he was: "Your stuff holds my eye. Most verse I merely slide off of." He guessed she was young (she was thirty-one, two years younger than Old Man Pound), but he wanted to make sure: "O what about your age; how much more youngness is there to go into the work, and how much closening can be expected?" Sports fans and coaches take for granted that there is a big difference in potential between an eighteen-year-old shortstop and one who's twenty-eight. In teaching, some of us might say the same thing about twenty-three-year-old poets and forty-three-year-old poets. Pound is clear here that he believes age matters in the education of artists: Can they still learn? Are they still alive? Though always a straight-shooting critic, he remarked, "There's no use cutting up a writer unless there is some chance of doing them some good."

Let's look at the good he tried to do twenty-one-year-old Iris Barry, who, though never becoming known as a poet, wrote books about the movies and became the librarian of the Museum of Modern Art:

Dear Miss Barry: It is rather difficult to respond to your request for criticism of your stuff. I am not quite satisfied with the things you have sent in, still many of them seem to have been done more or less in accordance with the general suggestions of imagisme, wherewith I am too much associated. The main difficulty seems to me that you have not yet made up your mind what you want to do or how you want to do it. I have introduced a number of young writers (too many, one can't be infallible); before I start I usually try to get some sense of their dynamics and to discern if possible which way they are going.

With the method of question and answer: Are you very much in earnest, have you very much intention of "going on with it," mastering the medium, etc.? Or are you doing vers libre because it is a new and attractive fashion and anyone can write a few things in vers libre? There's no use my beating about the bush with these enquiries. I get editorial notes from odd quarters blaming me that I have set off too many people....

Some of the things seem to me "just imagistic," neither better nor worse than a lot of other imagistic stuff that gets into print. If I am to hurl a new writer at the magazine with any sort of conviction I must have qualche cosa de speciale. I must have at least three or four pages of stuff which "establish the personality." At least I am not interested in the matter unless I can do that. I simply forward some mss. without comment.

In some of the "regular" stuff, you fall too flatly into the "whakty whakty whakty whakty whak," of the old pentameter. Pentameter O.K. if it is interesting, but a lot of lines with no variety won't do....

After making pointed criticisms of particular poems, he reflects:

(Of course if a thing moves one, all this minutiae is no matter, or not much matter, but a series of these minute leakages will sink a poem, or a group of poems.) . . .

He asks her:

I don't know whether any of these suggestions are any use to you, or whether you want to "have another go" at any of the poems you have sent in???? In any case I should like to see a large mass of your stuff, if there is a larger mass. (If there isn't or if there isn't going to be . . . it is not much worth my while arguing with an edittor.)

He's going to send in and recommend some of the poems for publication in Poetry, and if they're not accepted there, he has another publication in mind if she has more poems.

My present feeling is that "nothing is worth while save desire" and I am sick of verse without it. Or else there is a bitterness which shows the trace of desire, that also can make good verses, but placidity is a drug, at least for the season.

Ah well, you may have got a worse overhauling than you wanted, but one can't criticize and be tactful all at once. And at any rate, I shan't have kept you waiting six months for an answer.

The postal tutorial continues a week later with a lesson on revising. In regard to a poem called "Impression," he explains:

"Dissolve" is bad not only because it is, as I think, out of key with what goes before, but because it really means a solid going into liquid, and when you compare that to pear-petals falling, you blur your image. Conceivably, crystals suspended in liquid might dissolve quickly, but if they fell they would slip slowly through the water. At least the word bothers me. "Faster" may be the hitch; one doesn't always get the real trouble at the first shot, but one can sometimes tell about where it lies. You might say "Then we drifted apart" or forty other things; the phrase "friendship was dissolved" is I think newspaperish, and then it is passive and your comparison is active: "petals fall"; "was dissolved." . . .

It isn't so much "getting a better word" very often as doing a new line. . . .

He returns to this point (and not only in this letter):

The thing I notice in your emendations is that you stick very tight to the form or arrangement of words you have already used. Better get the trick of throwing the whole back into the melting-pot and recasting all in one piece. It is better than patching.

A new line or a new word may demand the rewriting of half a poem to make it all of a piece.

How difficult it is to teach ourselves to throw "the whole back into the melting-pot"! Texture, a continuous impression of an entire impulse, is what he's after.

That summer, the lessons continue. Citing Ernest Fenollosa, the scholar of Japanese and Chinese literature whose work brought about Pound's translations from those languages, who "inveighs against `IS,' wants transitive verbs," Pound explains to Barry a principle that writing teachers continue to preach:

"Become" is as weak as "is." Let the grime do something to the leaves. "All nouns come from verbs." To primitive man, a thing only IS what it does. That is Fenollosa, but I think the theory is a very good one for poets to go by.

Provoked by the comment of a poet friend of hers, he scolds her (and the friend) and another poet for seeming to believe that artists are sensitive plants who shouldn't expose themselves to the influence of others: "It is as bad as Cannell's being afraid to read anything for fear it would destroy his `individuality.' !!!!!!!!! . . . If a man has anything it can't be either taken from him or rubbed away." Having given her a reading program, he reviews it, with asides: "Shifting from Stendhal to Flaubert suddenly you will see how much better Flaubert writes. AND YET there is a lot in Stendhal, a sort of solidity which Flaubert hasn't. A trust in the thing more than the word. Which is the solid basis, i.e. the thing is the basis." (In ABC of Reading, he remarked: "I believe the ideal teacher would approach any masterpiece that he was presenting to his class almost as if he had never seen it before." He practiced this himself, keeping his mind open to new observations, even if they contradicted former convictions.) After various provocative, off-the-cuff statements on French, English, Latin, and Greek literature, he sums up "the whole art":

The whole art is divided into:

a. concision, or style, or saying what you mean in the fewest and clearest words.

b. the actual necessity for creating or constructing something; of presenting an image, or enough images of concrete things arranged to stir the reader.

Beyond these concrete objects named, one can make simple emotional statements of fact, such as "I am tired," or simple credos like "After death there comes no other calamity."

I think there must be more, predominantly more, objects than statements and conclusions, which later are purely optional, not essential, often superfluous and therefore bad.

Also one must have emotion or one's cadence and rhythms will be vapid and without any interest.

It is as simple as the sculptor's direction: "Take a chisel and cut away all the stone you don't want." ???? No, it is a little better than that.

After his tutorship with Iris Barry, he continued to take on other "students." Though more and more preoccupied and distracted by economic theories, he continued to be free and generous with his advice on reading and writing. In 1933, Mary Barnard, a twenty-four-year-old poet from Vancouver, Washington, applied to him for help, because, she remembers, "of all the reasons, I think the one that carried the most weight was that I was sure he would not write back, saying, `These are very good. You should keep on trying,' which was the last thing I wanted. If he liked them, I thought, he would do something." And he sure did! But before agreeing to get involved with Mary Barnard's poetic aspirations, he interviewed her via postcard:

Age? Intention? How MUCH intention? I mean how hard and for how long are you willing to work at it? . . . Nice gal, likely to marry and give up writing or what Oh?

Having persuaded him that she had enough "intention," he warned her, nonetheless: "Do understand that at yr. tender age too much criticism is possibly worse than none." In any case, "Certainly DONT try to be profound. Say what you have to say and don't worry re/ what you haven't.... Go on writing letters to me/ and when you have 20 poems that you yourself think worth printing, send me the lot. In the interim I will answer questions."

He sets her on to Greek, on to translation, and on to writing as a discipline:

Invent some form of exercise that don't depend on the state of yr. liver. Obviously an EXERCISE means something that tires some muscle.

With his usual boldness, he later tells her, "The only chance for you to get out and STAY out of what I calls `girl's stuff' is to sweat at GREEK language and metric. Don't ask me to write 400 pages of WHY. If you will learn enough GREEK you can BE."

He considers one of her poems:

"Lai" starts with something nearly a bad Sapphic line. Try writing Sapphics. And NOT persistently using a spondee like that Blighter Horrace [sic], for the second foot. If you really learn to write proper quantitative sapphics in the Amurikan langwidge I shall love and adore you all the days of my life . . . eh . . . provided you don't fill `em with trype.

Directions on how to avoid "trype": "You go on CHAWIN at them Sapphics/ with an Alcaic strophe on sundays."

In small ways and large, he helped her, a young, unknown woman he had never met. He helped her publish some poems: "I thought there were a couple of good ones but the young must be judged by the young, so I gave the best of `em to R (not Raymond) Duncan, and he thought two fit for Townsman." And then, in April 1939, Pound made a return to the U.S., and Mary Barnard, eager to leave her hometown and find work, met him in New York. He brought her to the Museum of Modern Art, where he introduced her to Iris Barry, and more or less commanded Barry to find Barnard a job. (Eventually she got one through Barry with Barry's brother-in-law at the University of Buffalo library collecting poetry manuscripts: "With one or two sentences casually spoken, Pound had made the connection between me and the one job in the country that I was best fitted to do," writes Barnard.) Though I was aware of how vital and immediate Pound's letters were, it wasn't until I read Barnard's memoir that I realized that, however interesting he was in person, he most fully lived on the page. He knew Marianne Moore, Harriet Monroe, and Mary Barnard for years before he met them, and they knew him as well. Having been in his presence for only a few hours, Barnard remembers riding a cab with him:

During the ride, he said that he did not know whether he could offer any stimulation in an interview that he couldn't give by letter, and he added, "My medium is the typewriter."

As Barnard got busy with her job, and became friends with William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore through Pound's introductions, she fell out of touch with Pound during the war, and didn't correspond with him again until he was committed to St. Elizabeth's Hospital.

This morning I got another letter [she wrote in her journal on April 5, 1946] with the copies of the poems I sent him returned all marked up, with marginal comment-the first time in all our correspondence that he has done that. I sent him four-one he didn't touch, and the others he slashed into, but with such point, that it did me a world of good. I haven't had any criticism at all for a long time, the truth being that I feel sure enough of myself now that there are few people I would take it from, or ask it from; and of the poets I respect, he's the only one, I think, whose direction is close enough to my own to criticize my poem and leave it still my poem.

She visited him at the hospital, and after an unsuccessful attempt at earning her living as a novelist, went back to Pound's lessons about Greek. In 1958 she published her great translation of Sappho, a book still in print. But Pound's response to her publication was to tell her "there is no decent translation" of Callimachus and Bion: "In other words, no pat on the head, no pat on the back, certainly no raptures, just a crack of the whip!" She didn't mind.

© 2009 by Bob Blaisdell.

Bob Blaisdell teaches and writes in New York City.