Across the evening sky, all the birds are leaving.

But how can they know it's time for them to go?

Before the winter fire, I will still be dreaming,

I have no thought of time.

Show the above lines to your English Lit prof, and the old man might guess Katharine Tynan, Sara Teasdale, or perhaps a translation of Verlaine. They are in fact the opening lines to the song “Who Knows Where the Time Goes”, written by folk singer Sandy Denny when she was all of twenty years old. Denny later recorded the song as lead singer of Fairport Convention, alongside classic ballads such as “Tam Lin” and “Matty Groves”. Those ballads arose from an oral tradition that saw music and poetry as different facets of the same art; most of antiquity had the same view, up to and after the invention of the printing press. When poets like John Donne or William Congreve wrote lyrics with the title “Song”, it wasn’t a conceit—they really did envision the poem being sung. Likewise Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty” and most of the famous poems by Robert Burns and Thomas Moore were written as lyrics, to be sung to one tune or another.

Following the free verse revolution (1910 and all that), poets distanced themselves from meter and rhyme, the lyrical structure demanded by most songs. Thus Berryman’s “dream songs” are all but unsingable, and any band attempting to make music out of Mary Oliver or W. S. Merwin will have a hard time of it. Musicians, however, not easily deterred, continue to embrace poets, if not sing their actual words. Robert Zimmerman took his stage name from Dylan Thomas, Peter Gabriel’s “Mercy Street” is based on a poem by Anne Sexton, and Andrew Lloyd Webber seized on a book of light verse by T. S. Eliot to create Cats.

Popular song lyrics have also changed, of course. Since the days of Nirvana lyrics seem to have become more oblique and informal, the lines taking on meaning only as an atmosphere of vague emotion, as in Haley Bonar’s “Daisy Girls”—

Maybe some bright morning

I'll comb my hair

And I won't want nothing

When I get to Camelot

Literary scholars have managed to more or less ignore song lyrics—at least until they are over a hundred years old. True, even the best lyrics, when set down on paper and divorced from their music, tend to look simplistic or even trite; yet for the vast majority of Americans, these are the “poems” we are most intimately acquainted with, and we love them on their own terms—the apt metaphors of “Stormy Weather”, the powerful narrative of “The Boxer”, the beautiful imagery in “Landslide”, the off-the-cuff bravado of “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction”, the sheer degradation of “The Old Main Drag”. Perhaps poetry isn’t dead after all—it’s simply hiding in a song.

- Joel Van Valin

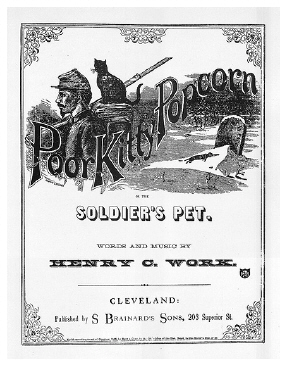

Lyrics by Henry Clay Work

The popular Civil War-era songs of ardent abolitionist Henry Clay Work (1832-1884) celebrate the Union cause with the frank sentimentality of their era, and his bold emotionalism can be strangely unsettling to the modern listener. Blunt, brazenly expressive stories of soldiers’ dying words, doomed waifs, and violent shipwrecks transcend their sensational milieu and read as authentic cries of pain from a catastrophic era.

Work’s most disquieting song is “Poor Kitty Popcorn, or the Soldier’s Pet”, the grim ballad of a Union infantryman who adopts a cat on the march. The southern feline joins a column of Union soldiers in fresh loyalty to the northern cause, or perhaps in the wake of disastrous Confederate attrition. One can easily imagine a hungry or lonely cat abandoning the ruined south for a new allegiance:

Did you ever hear the story of the loyal cat? Meyow!

Who was faithful to the flag, and ever follow'd that? Meyow!

Oh, she had a happy home beneath a southern sky

But she pack'd her goods and left it when our troops came nigh

And she fell into the column with a low glad cry, Meyow!

Beneath the fanciful tale, there’s a touching specificity that suggests a real cat, or at least a recognizable one, supplying steadfast if capricious, companionship:

Round her neck she wore a ribbon, she was black as jet, Meyow!

And at once a gallant claimed her for a soldier's pet, Meyow!

All the perils of the battle and the march she bore

Climbing on her master's shoulder when her feet were sore

Whisp'ring in his ear with wonder at the cannon's roar, Meyow!

In the worst of all ironies, the end of the war marks the demise of Popcorn’s master. Having survived combat, the “gallant” dies in the midst of a snowstorm:

Now the "cruel war" is over and the troops disband, Meyow!

Kitty follows as a pilgrim to the northern land, Meyow!

Ah! But sorrow overtakes her, and her master dies

While she sadly sits a-gazing in his dim blue eyes

‘Til by strangers rudely driven from the door she cries, Meyow!

Rejected, Popcorn follows her master’s body as it’s borne to a perfunctory burial on the plains, steadfast until the end:

So she wanders on the prairie till she sees his form—Meyow!

Carried forth and buried roughly 'mid the driving storm—Meyow!

Oh! Her slender frame, it shivers in the northern blast

As she seeks the sandy mound on which the snow falls fast

And alone amid the darkness there she breathes her last Meyow!

But then the grim finale of the tale has already been revealed in the chorus:

Poor Kitty Popcorn!

Buried in a snow drift now

Never more shall ring the music of your charming song, Meyow!

Never more shall ring the music of your charming song, Meyow!

The song first appears to be a conventionally sentimental gloss on war, but finally approaches something more devastating—an authentic evocation of combat’s grim wake. There is no redemption in the cheerless ending, no apparent reunion beyond the grave in the tradition of The Dog of Flanders and other bleak 19th century animal tales that leaven tragedy with promises of heaven. The whole narrative is a ruthlessly existential journey from hardship to death, redeemed only by small moments of companionship.

A 1974 recording by soprano Joan Morris and pianist William Bolcom, long out of print, captures the song as it was intended to be performed, with a spry solo vocal navigating Work’s torrent of lyrics against a major-key piano accompaniment. The music unfolds with the grim, quotidian certainty of a Mathew Brady photograph, made more painful by the “meyow” chorus and its counterposition of whimsy and disaster. For a moment, the sentimental songcraft of another era is unmasked as neither affectation nor camp, but a heartfelt expression of unfathomable loss.

The listener can look closer, but the details are excruciating: On the agonizing before and after artwork of the original sheet music, the prostrate and lifeless Popcorn appears next to a tombstone bearing the inscription REQUIES CAT IN PACE.

- Sten Johnson

Heartbreak Hotel

Lyrics by Tommy Durden and Mae Boren Axton

The 1950s. Boys and girls cruise into drive-thrus with the radio on. They're teenagers with wheels and places to go, and a record store just around the corner where they can spin vinyl: Pat Boone, Frank Sinatra and the Fontaine Sisters.

But that music is so 1955. This is '56, after all, and the new cat swinging his hips, hugging the mic to his chest like a girl he wants desperately, the man whose music blares from AM stereos, is Elvis Presley.

A date: February 21, 1956. Elvis is another Memphis boy with a guitar and a head of hair. But advance one day to February 22 and he is something more. That song of his—what's its name?—sets fire to the charts.

Well, since my baby left me

I found a new place to dwell

It's down at the end of Lonely Street at…

Well, you know the rest. History records the address. America's teenagers—the teeny-bopping, drive-in movie generation with their ducktails, fin-tails and transistor radios—find Elvis Presley at "Heartbreak Hotel".

Before Sgt. Pepper’s and the Summer of Love, there was Elvis Presley, born 1935 in Mississippi, and destined to be a blue-collar nobody until he found music. Sam Phillips, impresario at Memphis' Sun Records, discovered Elvis's voice. He chiseled away the fluff in an all-night recording session with guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black.

This was 1954 and Elvis was just

a guy off the street who'd been bugging Phillips for months to give him

a break. So Phillips did. But during that all-nighter, the record producer

nearly gave up. Elvis wanted to croon like his idol Dean Martin. He wanted

to warble and sigh into his microphone. But Phillips mined his performers

for country blues that put grit in your teeth. During a break in recording,

when Elvis was noodling with Moore and Black, just guys messing with the

blues, Phillips heard that unmistakable grit.

Daddy done told me too,

"Son that girl you're fooling with

She ain't no good for you."

What came out of the late-night session was "That's All Right", Elvis's first hit single with Sun Records. Yet his reach would remain limited to the South, until he signed with RCA in 1956 and recorded "Hound Dog", "Don't Be Cruel" and "Heartbreak Hotel". The latter was penned by Tommy Durden and Mae Axton and inspired by a newspaper article about a suicide who left behind a note with the haunting words, "I walk a lonely street."

That was the magic year for Elvis. Artistically, he never reached those heights again. Many blamed his service in the army. But the songs of '56 remained special, most of all, because they defined the sound and look of rock. The outsider menace. The handsome drawling simplicity, which artists like The Beatles and Led Zeppelin synthesized and elaborated for their generation. Yet even these artists, in composing their fresh, of-the-moment tunes, wandered old musical paths down Lonely Street to Heartbreak Hotel.

- Britt

Waterloo Sunset

Lyrics by Ray Davies

Of all the British Invasion bands, the Kinks were the most quintessentially English in character. They arrived on the scene in 1964, announced by the bashing guitar riffs of “You Really Got Me”. Initially known for their on-stage rowdiness (it got them banned from touring America for four years in 1965) their sound quickly matured, as did lead singer Ray Davies’ song lyrics. In sketches like “Dedicated Follower of Fashion”, “Afternoon Tea” and “The Village Green Preservation Society”, Davies employs a whimsical “Englishness” that is as much indebted to Noël Coward as to Chuck Berry or The Beach Boys. These songs often poke fun at British stereotypes: the town dandy, the nasty aristocrat in his country house, the “Swinging London” fad for flamboyant dress. “Waterloo Sunset”, off the Kinks 1967 album Something Else, is something more—a song about England itself.

Dirty

old river

Must you keep rolling

Flowing into the night?

People so busy

Make my feel dizzy.

Taxi lights shine so bright.

And I don't

Need no friends.

Long as I gaze on

Waterloo Sunset

I am in paradise.

It’s a pretty tune, and it has a particularly British quietness about it, pervaded with a detached melancholy. Ostensibly it’s a song about living in the city—the view of Waterloo Station, one of the busiest of the London Underground, shining as bright as the sunset. Our human propensity for loneliness and isolation in the midst of millions (that strange irony of large urban areas) is here seen in a comfortable, almost romantic, light.

As the song continues, two other characters, Terry and Julie, are introduced. They meet at Waterloo Station every Friday night, but they soon “Cross over the river / Where they feel safe and sound.” Terry and Julie may or may not be a reference to romantically-involved stars Terence Stamp and Julie Christie; in any case they, like the narrator, need no friends. It is as if the glittering cityscape has replaced human society itself, in the same way its artificial lights have replaced the real sunset.

There is, of course, another metaphor lurking in the shadows of “Waterloo Sunset”: the famous battle of Waterloo, where Wellington finally finished off Napoleon, perhaps the crowning moment of British history. In the Britain of the ‘60s, still rebuilding their battered towns from World War II, that golden era seemed, like the British Empire itself, to be quietly floating away. And so the song can be seen on three different levels: as a lullaby to London, an ode to alienation, and an anthem to the decline of England. And it perhaps also signaled the beginning of the decline of the Kinks—although they, like the dirty old Thames, kept rolling into the night.

- Joel Van Valin

Song to the Siren

Lyrics by Tim Buckley and Larry Beckett

"Did I dream you dreamed about me?" Troubadours were never quite so brazen when addressing their lady-loves; nor did Odysseus fool himself into thinking that sirens were capable of loving thoughts, only destruction. But a romantic, unattainable vision of the siren inspires the folk ballad "Song to the Siren", as does the kind of grand fate worthy of Greek myth. First performed by Tim Buckley on the last episode of "The Monkees" in 1968, it's loftier than its pop culture origins, with one chiming guitar to offset somber lyrics:

On the floating, shapeless oceans

I did all my best to smile

'Til your singing eyes and fingers

Drew me loving into your eyes.

And you sang "Sail to me, sail to me, let me enfold you."

That verse, and the next, end with a quote that is dutifully analyzed in the subsequent verse—a pattern familiar to any unrequited lover hanging onto any acknowledgment. Whether the siren's embrace will entail divine cuddling or mythical death, the sailor is hooked, and capsized when she switches gears in the next verse: "Touch me not, touch me not, come back tomorrow."

With such spare music and bare longing, "Song to the Siren" poses a challenge to singers of all genres: Sinead O'Connor recently recorded it, and it's a favorite live song for Robert Plant. The best-known cover is nearly a capella: Elizabeth Fraser of the Cocteau Twins sung it in 1983 with the 4AD record label's house band, This Mortal Coil. Fraser's soprano-sax voice sustains this "Song to the Siren" over the years, appearing frequently in pop culture as a shortcut to a lusty or funereal mood: from a literally incandescent sex scene in "Lost Highway" to French perfume commercials and a recent movie adaptation of Alice Sebold's grim novel The Lovely Bones, the sailor's ordeal tugs the heart in all directions.

At last, when rejected by the siren, the sailor dallies in fatalism: "Should I stand amid the breakers? / Or shall I lie with death my bride?" Many other contemporary songs dwell on such anguish, but only Buckley understands that disenchantment eventually makes a lover more confident and worldly, ready to seduce his original fixation or some new catch. Odysseus stuffed wax into the ears of his sailors—literature's first earplugs—so that they wouldn't be tempted by the siren's song. But in these lyrics, the sailor survives by willpower alone, and he is stronger for having known temptation:

Hear me sing: "Swim to me, swim to me, let me enfold you.

Here I am, here I am, waiting to hold you."

- Iris Key

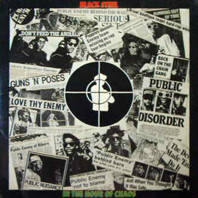

Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos

Lyrics by Carl Ridenhour (Chuck D.)

Public Enemy transcends the rap genre by blending the anti-authoritarian methodologies of the hippie and punk eras, and the influences of the Black Power and Civil Rights movements, encouraging the oppressed to drop out of the system, and if that doesn’t work, then to fight it. These messages proved extremely popular, speaking to audiences eager to re-kindle class consciousness and dismantle the crass materialism and inhumanity ‘80s economics. These conditions rocketed Public Enemy to well-deserved fame and notoriety during the apex of the pro-materialist era in which they first appeared. Along with other pioneering hip-hop artists, Public Enemy demonstrated a mastery of craft in the evolution of applied poetry, and an ability to ignite social consciousness in an effort to change the status quo.

Public Enemy proves that words are the most powerful weapon of the revolution, and that truth is both the armor and the bullets. In “Black Steel In the Hour of Chaos” (from the album It Takes A Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back, released 1988) both words and bullets fly in what amounts to a hip-hop ballad. The plot follows a first-person narrator who contemplates how he was put into prison, and then explains his planned escape while raising the political issues underlying his confinement. Throughout the album and within the crucible of this song, themes of slavery, racism, militancy and resistance are targeted and dispatched with lyrical precision and fiery moral certitude. Toward the beginning of the song, the narrator becomes a prisoner:

They could not understand that I'm a Black man

And I could never be a veteran.

The narrator is then further victimized by the system that he was already alienated from to begin with. It often seems that Public Enemy mixes pacifism and militancy in equal amounts, but its songs only celebrate militancy where reasoning has failed. Thus, after attempting to dodge the draft and being placed in prison, the narrator decides to break out. Although riot and revolution are determined to be the only alternatives, violence is still not the sole method. Once the narrator captures several corrections officers, he explains:

Six COs we got we ought to put their head out

But I'll give 'em a chance, ‘cause I'm civilized

He’s not hoping to kill anyone, but merely escape from the intolerable conditions he’s been forced to endure. In the lines that immediately follow, the narrator justifies his actions so far and offers up what must be the most succinct and poetic explanation of what it means to be a revolutionary that I have ever encountered:

As for the rest of the world, they can't realize

A cell is hell—I'm a rebel so I rebel

Between bars, got me thinkin' like an animal

One of the COs tries to get away,

prompting the narrator to shoot the officer, thus demonstrating that words

without actions are empty. This raises the question at the heart

of Public Enemy’s message: is it wrong to fight against conventional injustice

using unconventional means? Many would chuckle at the notion of

a morally acceptable prison break, but what if the situation involved

an American soldier breaking out of an overseas prison camp? Public

Enemy launches rockets at the hypocrisy of maintaining an unjust system

in the service of nationalistic ideology. Perhaps mainstream critics

would prefer that the narrator of this song write letters to Amnesty International

and quietly wait for a re-trial. Without a contextual understanding

of African American history or sympathy for their struggle for equality,

it is all too easy for the mainstream establishment to write off edgy

hip-hop artists as jumping too quickly to violent solutions or imagery.

But one must understand that the violence embodied in some rap

lyrics is metaphorical, not literal. It simultaneously provides

catharsis and represents the desire to obtain liberty and justice by other

means, after mainstream participation in the system has been vigorously

denied. Public Enemy highlights the moral ambiguities of attempting

to extract justice through violence in almost every song, and continuously

stresses the value of skepticism toward authority. Given the horrendous

violence visited upon the Black community over the years by the American

socioeconomic system, it is not surprising that any talk of payback—even

in a metaphorical sense—would send a chill up the spines of those who

have inherited the reins of that system.

One of the COs tries to get away,

prompting the narrator to shoot the officer, thus demonstrating that words

without actions are empty. This raises the question at the heart

of Public Enemy’s message: is it wrong to fight against conventional injustice

using unconventional means? Many would chuckle at the notion of

a morally acceptable prison break, but what if the situation involved

an American soldier breaking out of an overseas prison camp? Public

Enemy launches rockets at the hypocrisy of maintaining an unjust system

in the service of nationalistic ideology. Perhaps mainstream critics

would prefer that the narrator of this song write letters to Amnesty International

and quietly wait for a re-trial. Without a contextual understanding

of African American history or sympathy for their struggle for equality,

it is all too easy for the mainstream establishment to write off edgy

hip-hop artists as jumping too quickly to violent solutions or imagery.

But one must understand that the violence embodied in some rap

lyrics is metaphorical, not literal. It simultaneously provides

catharsis and represents the desire to obtain liberty and justice by other

means, after mainstream participation in the system has been vigorously

denied. Public Enemy highlights the moral ambiguities of attempting

to extract justice through violence in almost every song, and continuously

stresses the value of skepticism toward authority. Given the horrendous

violence visited upon the Black community over the years by the American

socioeconomic system, it is not surprising that any talk of payback—even

in a metaphorical sense—would send a chill up the spines of those who

have inherited the reins of that system.

While frightened, mainstream audiences hone in on violent imagery, Public Enemy’s lofty ideals and complex reasoning often go quietly unnoticed. Part of the complexity stems from the various divergent influences and personalities involved. Chuck D and Flavor Flav both attended university together while Professor Griff came on board later in the role of “Minister of Education.” Chuck D could be viewed as the heart and conscience of Public Enemy while Griff was the hip-hop band’s tie to Black identity politics and Flav was the court jester. A key feature of Public Enemy is a group of bodyguards/stage performers called the S1W (Security of the First World), which actually originated as a group of martial artists founded by Professor Griff, some of whom were philosophical followers of the Nation of Islam. They publicly dressed and featured roles in some songs as a commando unit. Unfortunately, the heady mixture of fame, militant posturing, diverse ideologies and divergent personalities could not hold together forever. Griff later alienated audiences by making anti-Semitic comments, and Flavor Flav experienced drug problems. Public Enemy reached their zenith by 1989 and by the end of the ‘90s their star had fallen even as their legend arose. Through the powerful medium of Chuck D’s commanding oratory, Public Enemy left its mark on thousands of artists and audiences by daring to make Black identity politics and class consciousness their primary themes at a time when mainstream American culture cared little about either.

- Justin Teerlinck

Hello My Name Is Your TV

Lyrics by Andrew Volpe

“Hello My Name Is Your TV” is off of the first album recorded by Ludo, a band that clearly has a great interest in love. Many songs of love can be found on this self-titled CD: girl that got away, girl that you fantasize about, girl that you are not even sure is real … oh, and the TV!

“Hello My Name Is Your TV” is sung from the viewpoint of (you guessed it!) a TV. It is obvious that there is a relationship going on between this heart-sore sentient box of metal with wires and the young man who devotes a good amount of his time and life watching it.

Hello, my name is your TV

We’ve been together so long

So many memories

We solved so many problems

Situated comedies

The TV explains the difference between the true reality and the one that the young man wishes to belong to:

Here, see California, where pretty people dream

And the good guy gets the girl by the sunny sea

The young man, for whom we have no name or accurate age group, comes from a broken home, where his parents fought all the time while he was sitting before his old friend the TV (which he seems to have inherited). Sometimes when you have no real way of leaving your problems behind, all you can do is escape.

I’m sure that as a kid this young man was imagining himself on reruns of The Wonder Years or The Brady Bunch while listening to his mother and father yell at one another. As he gets older, he just has no luck! No romantic relationships (“All the girls, they lie and they break your heart”). And why would he bother with them if he could have his dream girl appear on screen like clockwork? Let’s hear it for Marsha, Marsha, Marsha!

I don’t think he has friends. I really think that all he’s got is that TV. Sad, isn’t it?

I have gone online to see what others think of this song. For some reason there is a popular idea that the lyric “Here, see California, where pretty people dream/ Now see that icy vacant lot where they made your nose bleed” indicates that our poor young man is dead. Aside from being a hemophiliac, I ask my peers: How the heck can a nosebleed kill you?

It is clear in the song that this guy has just had enough. The TV even says “Here take my hand, I’ll take you home. / You’ll never have to be alone.” Which is true. This kid goes home to where the heater is already on; there is a blanket or two near his couch, and he proceeds to escape from his current really substandard reality.

The lyrics have a certain mystery to them. Does he actually get pulled inside the TV? Not physically, of course, but you could wonder.

You could love your TV—but how comfortable would you be if it loved you back?

- Julia Diaz-Perrish

Vapour Trail

Lyrics by Ride (Andy Bell, Mark Gardener, Stephan Queralt, Loz Colbert)

The ability for a song to affect someone is a highly personal and possibly complex matter. This is one of the few songs that brings tears to my eyes. To me, the song is about mortality, impermanence, the brevity of life’s events and moments, both big and small. People come and go. Things don’t last. The writer here is contemplating the sublime beauty of a jet aircraft’s simple vapor trail (contrail) in a blue sky. As a metaphor this analogy applies to the fragility of all matters in life—friends dying, friends moving away, social systems shifting and collapsing, loss, the changing landscape, the changes people are forced through. The lyrics are simple, elegant, and direct—

I watched you for a

while

You are a vapor trail

In a deep blue sky

This song reminds me of all the past friends I don’t see any more, all the people who have moved on, all the places I used to go and things I used to do, and the people therein who are no longer available to me. Why they only lasted what seems now to be just a moment is beyond me. But to me these moments and people are also as beautiful, fragile, sublime, and as temporary as a jet aircraft’s simple vapor trail in a deep blue sky. Songs like these remind me to enjoy what is around me, as they don’t always last.

The song ends on a plea to take in the beauty around us and recognize what we have while we have it—

We never have enough

Time to show our love

The band’s career mirrored the sentiments of this wistful, mournful song. Ride rocketed to fame in their native England in 1990 but had faded out by the mid-Nineties. They were one of the forbearers of the “shoegaze” and “dream pop” genres, terms that were initially meant to be dismissive (as band members stared at their shoes as they droned away), but were later considered descriptive of the band’s dreamy, contemplative, slow drone and thoughtful lyrics in a wash and blur of ringing and atmospheric guitars and chugging rhythms. Their style was a mix between pastoral whir, melodic whoosh, hazy psychedelic revival, and chiming, dense Britpop of the era—a mix of slow and fast dynamics. Nowhere, the album “Vapour Trail” appears on, is considered the second-best record of the shoe-gaze era.

Ride had an initial enthusiastic core following. But as the band evolved to emulate their late ‘60s and classic tastes in an attempt to expand their music and audience, they lost their dedicated followers without gaining converts. Ride seemed to lose its direction and fragmented.

There are still droning shoe-gaze bands around, but the height of this subgenre has long since been lost as new strains and trends rise and fade. It seems some things never last, and like a vapor trail in a deep blue sky, you just have to appreciate them for the brief time they do.

- Tony Rauch

Visions of Johanna

Lyrics by Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan in his early career was a folk singer of restless, heart-felt poignancy, and his song lyrics were firmly derived from the Anglo-Irish folk tradition. “Girl from the North Country”, for example, borrows its opening from “Scarborough Fair”, and the beautiful “Boots of Spanish Leather” is chiefly a dialogue between two lovers, in the pattern of old ballads like “Barbara Allen” and “The Daemon Lover”.

Dylan became more adventurous in the mid-Sixties, and under the influence of poets like Arthur Rimbaud and Allen Ginsberg he turned out original, free-form lyrics that were by turns playful, caustic, and surreal. At the same time, however, the emotional range of his music narrowed, crystallizing in the iconic Dylan persona: detached, cynical, deadpan—a contrarian who refused be a player on anybody’s team.

Recorded in late 1965, “Visions of Johanna” would wind up on the legendary Blonde on Blonde album. It’s a song which defies a strict categorization or interpretation, yet nags at the listener, longing to be understood; the revelation of something important, perhaps even holy, can be felt in Dylan’s tired vocals and the lazy accompaniment of guitar, organ and harmonica. The opening lines paint the backdrop: it is night in a disreputable quarter of (probably) New York, a place with empty lots where “the all-night girls they whisper of escapades out on the ‘D’ train.” The singer is in a loft with “Louise and her lover so entwined” (whether that lover is the singer himself is not explained) but he is thinking of Johanna, now absent.

Louise, she’s all right, she’s just near

She’s delicate and seems like the mirror

But she just makes it all too concise and too clear

That Johanna’s not here

And then there is one of those Dylan lines that stop you dead in your tracks:

The ghost of ’lectricity howls in the bones of her face

Where these visions of Johanna have now taken my place

As with Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, the ghost-like Johanna seems to wield far more power than anyone now present on the scene. But who is she? Some have suggested that “Visions of Johanna” is an autobiographical song, and that Johanna is Joan Baez, whose romantic involvement with Dylan was coming to a close by late 1965. Most listeners seem to take it as a simple love triangle, the narrator dreaming of his glorious past with Johanna while in the presence of his tepid current lover, Louise. Yet the song is not about memories but visions, suggesting glimpses of some holy or inspired presence now departed.

After a stanza where Dylan, with typical nastiness, dismisses a “little boy lost” who “takes himself so seriously,” the scene shifts abruptly to an art museum. The usual paintings are on display: the “jelly-faced women” (including one with a mustache), the “primitive wallflowers,” and the Mona Lisa herself, who “musta had the highway blues / You can tell by the way she smiles.” Here, in the temple of art, we hear of Johanna again:

Oh, jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule

But these visions of Johanna, they make it all seem so cruel

In the last stanza, amid the usual Dylan procession of allegorical characters (“the fiddler,” “the countess,” “the peddler”) we hear of Madonna, who “still has not showed.” The song then ends with a musical reference:

The harmonicas play the skeleton keys and the rain

And these visions of Johanna are now all that remain

What could it all mean?

If we read “Visions of Johanna” not as a love song, but a lament for the loss of art and inspiration, the stanzas begin to fit together like the pieces of a stained glass window. Both the singer and Louise, and perhaps even the “little boy lost,” are artists in a dead, postmodernist world of fish trucks, country stations and surrealist painting, lifeless and void of sanctity. Art is no longer created for religious devotion or spiritual fulfillment, but merely as a commercial proposition. Johanna might represent a muse of sorts, or unattainable perfection—a passion, or inspiration that once touched the singer but has since gone, leaving “a farewell kiss to me.”

Which brings us back to the jingle-jangle morning of Dylan’s early days, and a verse from “Boots of Spanish Leather”:

Oh, but if I had the stars from the darkest night

And the diamonds from the deepest ocean

I’d forsake them all for your sweet kiss

For that’s all I’m wishin’ to be ownin’

For all its enigma and imagination, “Visions of Johanna” is somehow a lesser song—one with brilliance but no heart, left stranded in the bitterness of its own benighted cityscape.

- Joel Van Valin

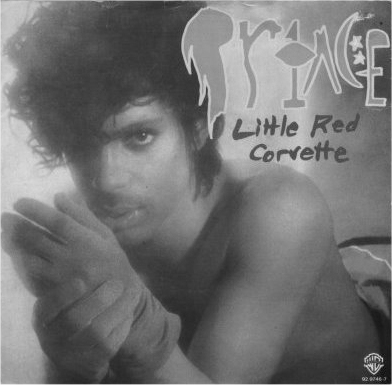

Little Red Corve tte

tte

Lyrics by Prince

I guess I shoulda closed my eyes

When you drove me to the place

Where your horses run free

In 1983, Prince released “Little Red Corvette”, his first song to reach top-ten status on Billboard. The song is based upon a metaphor in which Prince likened a sports car to a promiscuous woman. My aunts adored Prince, and so as ten-year-olds my cousin Lisa and I were lucky enough to listen to the uncensored versions of his songs. My aunts, thinking that we were young and naïve, never chased us out of the room when they were playing Prince. Little did they know, we were able to deduce the symbolic references of horses and jockeys and all the other allusions to sex. This was pivotal in breaking me out of a rigidly conservative Catholic school brainwashing. According to Prince, everyone was not abstaining from pre-marital sex, even though the nuns were telling us otherwise. Aside from his risqué lyrics, I loved his crazy hair, and his tight and flashy suits and high heels. I was fascinated with this man and indebted to him for setting the record straight.

Prince has been an influential person in the music industry for decades and has helped foster the careers of many musicians. Aside from his enormous vocal range as a singer, he is also a guitarist, pianist, song writer, dancer, actor and owner of a recording studio and record label.

Prince drifted in and out of my music attention in my teens, but when I moved to California in 1997, I decided that while driving I would play “all Prince, all the time.” During this time, “Little Red Corvette” became my favorite song. The song became part of my long distance running pre-race ritual. “Baby you’re much too fast” was the exact phrase I needed to motivate me before road races. The inspiring words, fast tempo and high-pitched yelps helped psych me up to win.

Back in Minnesota, I was fortunate enough to see several of Prince’s concerts at the Xcel Center and Paisley Palace. While he did not influence my taste in cars, he certainly had an influence in my childhood and beyond. Thanks for the ride, Prince!

- Deanna Reiter

Bomber

Lyrics by Ian Fraser “Lemmy” Kilmister

Not long ago, I chanced upon a Reader's Digest Condensed Book that contained the following unlikely bedfellows in a single volume: Ewan Clarkson’s Halic, Jack Finney’s sci-fi time-traveler Time and Again, the Janice Holt Giles western Six-Horse Hitch, William E. Barrett’s A Woman in the House, and Len Deighton’s RAF thriller Bomber. The least canonical of the group is likely Halic, the dialogue-free story of a Grey Seal. Bomber has lived into infamy as the inspiration for veteran British trio Motörhead’s 1979 LP of the same name, with a title track that serves as a much more fierce, bellicose distillation of Mr. Deighton’s work than the meek volume I held in my hands.

Formed in 1975, Motörhead is a band known for its loudly assaultive, fast-paced brand of music, described by leader and bassist/vocalist Ian Fraser “Lemmy” Kilmister as “One half punk, one half metal and one half rock and roll.” His many lyrical obsessions include military history, and viewers of the 2011 documentary “Lemmy” will recall the now-65 year-old raconteur and musical legend sitting by a World War II Skoda tank, describing its technical specifications in disturbingly academic detail.

Musically, “Bomber” is ferociously accelerated rockabilly, accompanied by Lemmy’s gruff baritone, a virtual approximation of a real ride in the gullet of a Lancaster bomber, only louder. The song commences with pre-raid braggadocio as the listener imagines a quartet of Rolls-Royce Merlin V12 engines roaring into life:

Ain't a hope in hell, nothing's gonna bring us down

The way we fly, five miles off the ground

Because we shoot to kill, and you know we always will

It's a Bomber

But then, like a bombardier’s-eye view of a Ruhr Valley target, the proceedings become more abstract and occluded, a fever dream in a fire fight:

Scream a thousand miles, feel the Black Death rising moan,

Firestorm coming closer, napalm to the bone

The bomb bay opens and a barrage is unleashed. The Dortmund metal works collapse under a 22,000-pound payload and the Axis takes it on the chin:

It's a Bomber, it’s a bomber, it’s a bomber!

Specific lyrics actually matter little in this song, which relies on vocals as a pulverizing instrumental effect, mixing Lemmy’s guttural sprechgesang and its bass/guitar/drums accompaniment into a cacophonous, midrange-bound roar. Music critics are notorious for metaphors that try, in vain, to evoke this kind of melodic mayhem: the more aggressive the band, the louder the song, the better to pummel their readers with new figurative battle-odes. I won’t go any further, except to say that the overall effect is enchanting to my ears and cruelly oppressive to others.

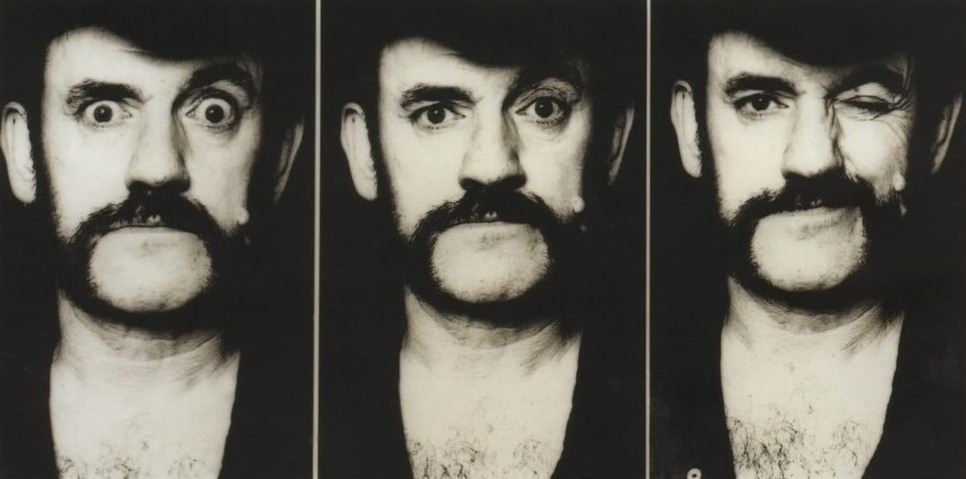

Lemmy is known for his iconic lamb chop beard-mustache

combo, a look that derives from Civil War Union general Ambrose Burnside.

But Burnside was timid in the field. Motörhead is more like William Tecumseh

Sherman, practicing a scorched earth approach that achieves elegance

in its utter bruta lity.

lity.

It's a Bomber, it’s a bomber, it’s a bomber!

- Sten Johnson![]()