If you ever come across a zettarella, make it your most prized possession, for they are quite special, and there are only a few of them left.

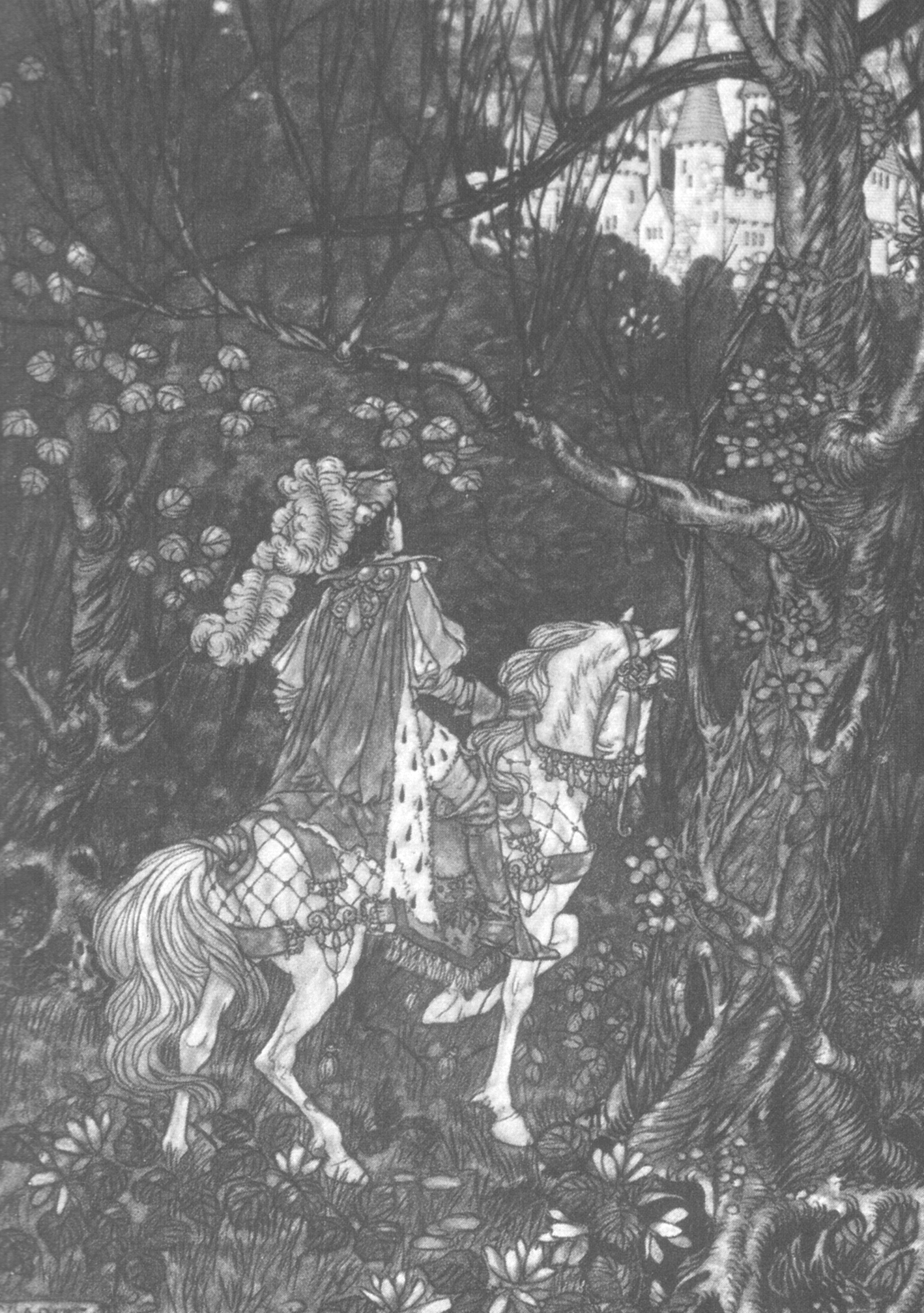

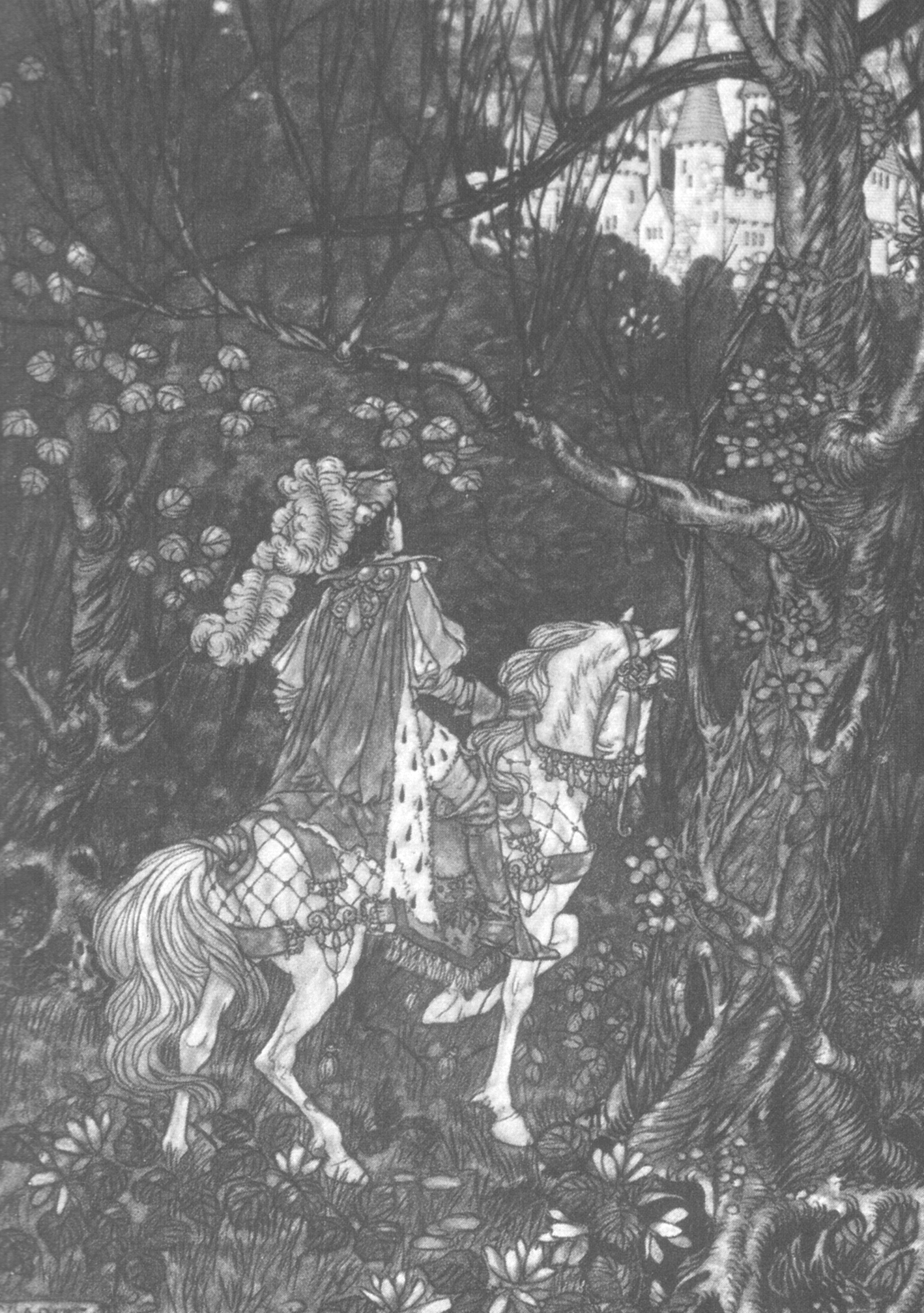

Our story takes place long ago and far away in a kingdom

near the sea. Prince Orzone ruled the land while his uncle, King

Faircloth, was away, said to be minding to matters of state in a distant

country. Prince Orzone was not a gentle ruler and the people despaired,

as the good king had been gone for years and many feared that he would

never return.

Among the prince’s subjects was a poor luthier named Jeremy Fruittree who lived in a humble cottage with his wife Ella and his son Zettar. Jeremy Fruittree eked out a meager existence building lutes, lyres, harps, violins, and zettarellas which he sold to musicians throughout the land. Jeremy’s instruments were quite fine, but being a man who loved the sound of beautiful music more than the sound of golden coins clinking together in his pocket, he remained poor. For he would give a lute, lyre, harp, violin, or even a zettarella free of charge to any poor soul who had a son or daughter who longed to play sweet music but did not have the means to pay for one.

Although the lutes, lyres, harps and violins made by Jeremy Fruittree were built with the utmost precision, care, and craftsmanship, none of those instruments could compare to his zettarellas. These zettarellas had within their wooden bodies such honeyed tones that a single note plucked on a single string could bring joy and happiness to even the most dourly-disposed person. And a sad chord strummed just once by a mere novice zettarella player could call forth such heartfelt emotions from anyone within earshot that the listener’s wails and tears were sure to follow immediately.

Now Jeremy Fruittree was indeed a craftsman who built his instruments with precision and care, but the truth of the matter was that the beauty of the music produced on his zettarellas was not entirely due to the luthier’s instrument-building skill nor to the skill of the musician playing it. The reason behind the magical music emanating from the zettarellas was due to something else entirely—it was due to a tree.

You see, some years earlier, when Jeremy Fruittree was just learning the art of luthirey, he had, one day, been out scouring the woods for proper lumber out of which to build a violin when he realized that he had wandered deep into a forest heretofore unbeknownst to him. Entering a small clearing he came upon a tree that was unlike any he’d ever seen. It was no more tall nor solid than its neighboring trees, but its leaves were something to behold, for they were of two varieties; both long, deep green needles, and flat variegated fronds in vivid autumnal colors. And as the wind blew gently through the tree’s branches, the needles brushed against the edges of the fronds and produced a unique sound that made Jeremy Fruittree’s ears tingle with pleasure. It was not a dry, rustling, crackling, leafy sound, but rather a wonderfully watery, shimmering, harmonious, singing sound, choir-like and mesmerizing.

Jeremy took up his saw and cut a stout branch from the tree, not so large that he couldn’t haul it back to his cottage, but still enough wood to yield a violin or two.

Upon reaching home, Jeremy immediately set to sawing and shaping the wood into the parts of a violin. However, his saw seemed to have a mind of its own; no matter how carefully he tried to guide it, the saw cut the wood into unusual shapes that Jeremy had never used before in building an instrument. Finally, as he failed in his attempt to correctly cut the last chunk of the wood, he became discouraged and swept all of the oddly-shaped pieces off his workbench and onto the floor. ‘Perhaps,’ he thought, ‘it will make decent firewood.’ As he stooped to gather the wood, however, he saw that the pieces had fallen all in a row. Looking more closely he noticed that the edge of the first piece was a perfect mate to the edge of the second piece. And so, on a whim, he picked up the two pieces and glued them together. As the glue was drying he inspected the next piece that lay upon the floor and saw that its edge was a perfect mate to the second piece that he had just glued to the first piece, and so he picked it up and glued it to the second piece. Jeremy worked through the night gluing perfectly matched piece to perfectly matched piece, all the while marveling at how beautifully the pieces joined together, but not paying attention to the overall shape of the structure he was creating. Jeremy attached the final piece just as the sun rose and lit the darkened workshop. He was amazed to see that the result of his labors was an instrument, one unlike any other. It was both round and square, it had bridges and fingerboards and tuning pegs and sound holes not entirely unlike those on other instruments, but not in the normal places. He fitted the thing with all the strings of a lute and a violin and a lyre and a harp. When he strummed those strings such a feeling of joy and peace and love washed over him that he immediately wanted to share the sound and the feeling with his wife and son. “Zettar, Ella,” he called out, and as he did so he knew what to name his new instrument.

Jeremy Fruittree was up early the following morning and off to the forest to chop down the tree and harvest its wood so that he could build more of the amazing zettarellas. After some time he found his way back to the clearing and to the zettarella tree. He took up his broadax and was about to bury its blade in the trunk of the tree when he noticed what looked like writing in the slab of bare wood where he had, the day before, cut away a branch. He lay down his ax and, looking more closely, saw chiseled into the tree, in the most exquisite calligraphy, the following:

If just one limb a year is all you take,

Such music we shall make,

And the magic of my wood

Will always do you good.

But if greed makes you cut more,

There’s nothing good in store,

And what might be best for me

Will be the ruin of thee.

Jeremy Fruittree knew then that the tree was magical and decided without hesitation to heed its warning.

And that is how it came to pass that once each year Jeremy Fruittree found his way back to the clearing in the woods and cut a single limb from the tree from which he produced one amazing zettarella. During the rest of the year he continued to build lyres and lutes and violins and harps. Years passed and Jeremy Fruittree was quite content with his life.

Then one day while he was hard at work shaping wood for a harp, he was startled when the door to his workshop was thrown open and Prince Orzone and five of his soldiers strode in without so much as bothering to knock at the door.

“Luthier Fruittree,” Orzone said, “I have heard that your instruments are quite….exceptional, and I wish to have one. If your instrument meets with my satisfaction I may even pay you for it,” he added with a sneer.

Being a humble man, Jeremy Fruittree bowed and said, “Perhaps Your Highness the Prince would like to try one of my violins.”

“Not a violin,” responded Orzone in a voice that was not friendly.

“Ah, I see,” said Jeremy Fruittree. “Perhaps one of my harps; I happen to have one right—”

“Not a harp,” interrupted Orzone in a voice that was dark and foreboding.

“Well then,” said Jeremy Fruittree, “a lute?...Or a lyre?”

“No and no,” responded Orzone in a voice like a clap of thunder. “You know what I want, and I shall have it…bring me a zettarella.”

“Ah, a zettarella,” sighed Jeremy Fruittree. “You see, at present I haven’t the wood for a zettarella, and even if I had the wood and could build one, I couldn’t give it to you as the next one I build has been promised to the daughter of a man whose—”

“Enough,” interrupted Orzone, and this time there was lightning in his voice. “There are forests upon forests of wood for the taking, and so tomorrow you will go into the forest and cut a tree and you will build me a zettarella.”

A small voice then interjected, saying: “He cannot get the wood because it comes from a magic tree that cannot be cut from more than once a year.” This statement came from young Zettar, who, unbeknownst to the others, had crept into the room and been listening to their conversation.

“Magic?” scoffed Orzone. “We shall see about that. Tomorrow you will bring me and my royal woodsman to your magic tree and we’ll see if it is not possible to cut wood from it more than once a year.”

“I cannot do that,” replied Jeremy Fruittree, “I cannot.”

“Ah, but you will,” replied Orzone, “if you wish to see your son again.” And with that he scooped up little Zettar, jumped onto his horse and rode off.

The following day Prince Orzone returned to Jeremy Fruittree’s cottage, without Zettar. “Come, luthier,” he said to Jeremy Fruittree, “lead us to your tree. Your son will be returned to you when the tree has been cut and the zettarella is mine. If, on the other hand, you refuse to cooperate ... well, all I can say is that there will be suffering.”

With a heavy heart, Jeremy Fruittree led the way into the forest and into the clearing where the zettarella tree stood.

Orzone gazed at the tree for a moment. “Yes,” he said, “the tree is unique. But it is made of wood and needles and leaves like any other tree and so it can be cut down and its lumber harvested for whatever use I demand. Cut the tree down…NOW,” he yelled to his royal woodsman.

The royal woodsman took a mighty swing and his ax bit deep into the trunk. Again and again the woodsman swung the ax, and with each wedge of wood chopped away from the trunk there seemed to come from deep within the tree the sound of crying or perhaps laughing. Finally, when the tree appeared ready to fall, the royal woodsman turned to the prince and in a quivering voice said, “Your highness, I dare not…”

“Oh, for pity’s sake,” yelled the prince, “give me that ax.” And, taking up the tool, he made the final chop to fell the tree. The tree swayed to and fro and began to fall away into the woods. But just as it was about to strike the ground, it suddenly snapped back to an upright position and tipped … in the direction of the prince. Orzone turned to run but was not quick enough and the tree crashed directly on top of him, striking him dead.

And then, to the amazement of Jeremy Fruittree and the various other onlookers assembled in the clearing, the felled tree began to shrink and shift in shape. The trunk became a waist and legs, the lower branches arms and the upper branches a neck and head…a royal head. And suddenly standing before them was King Faircloth, weeping and laughing and shouting for joy all at the same time. When, at last, he was able to compose himself he described how his brother, Orzone’s father, had, on his deathbed, compelled a sorcerer to cast a spell over Faircloth, turning him into a tree so that Orzone could ascend to the throne. The spell could only be broken by cutting the tree down, something that no sensible man would want to do.

King Faircloth christened Jeremy Fruittree his royal luthier and invited him and his family to live in the castle, which they did. Jeremy continued to build lyres, lutes, violins, and harps for the rest of his life. But, of course, never again a zettarella.

And that is why, if you ever come to own a zettarella, you must make it your most prized possession. For there will never be another made.