WHISTLING SHADE

|

WHISTLING SHADE | |||

|

|||

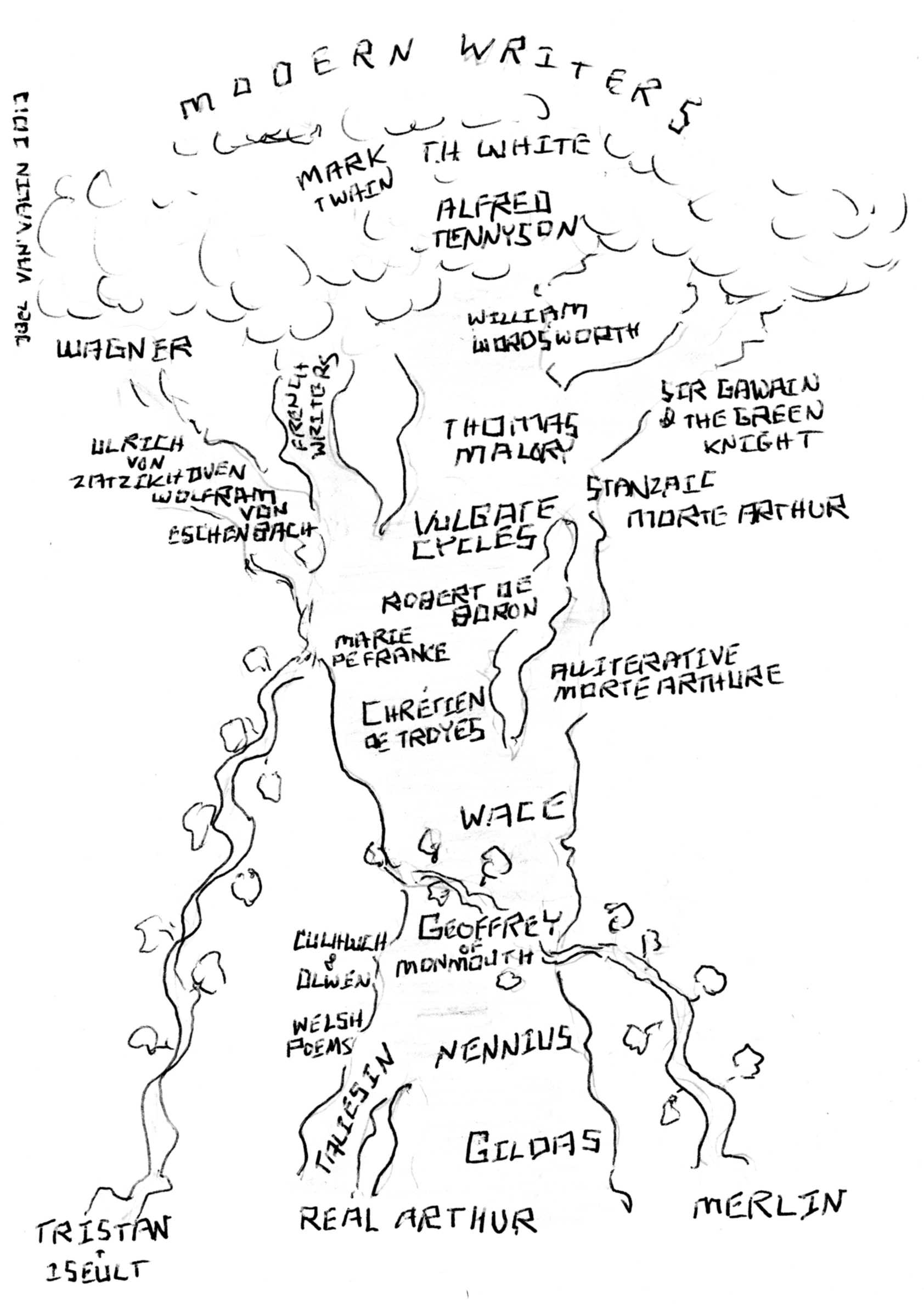

I was not born to live a man’s life, but to be the stuff of future memory,” Arthur tells Guenevere near the end of John Boorman’s 1981 film Excalibur. He adds, rather wistfully: “The fellowship was a brief beginning, a fair time that cannot be forgotten. And because it will not be forgotten, that fair time may come again.” King Arthur did not, indeed, live a man’s life; the Arthur we know is one invented by writers like Geoffrey of Monmouth and Chrétien de Troyes. And the “fair time” that was Camelot happened only in the pages of books. Nonetheless the edifice of Arthur’s legend, the “Matter of Britain” whose first stone was laid some fifteen hundred years ago, seems almost as durable as history itself. Its characters have been projected onto the vast canvas of Western mythology; its setting—the half-real, half-fantastical world of Dark Ages Britain—forms the backdrop of our cultural identity; and the tapestry of its themes is so rich that each century can trim it to fit, whether it be courtly love in the time of Eleanor of Aquitaine or the dashing idealism of the Kennedy administration.

The “real” Arthur is lost in the murk and turbulence of post-Roman Britain, his very existence a matter of debate among medieval historians.1 Because of the dearth of historical records from the era in which he supposedly lived (roughly, the early sixth century) the real-life Arthur and his court are entirely a matter of speculation. If they did once exist, suffice it to say they would not have recognized themselves in the Arthurian legend we are familiar with. That legend was shaped by dozens of writers—poets, prelates, historians and minstrels—in various countries over the centuries. Some of those authors became legends in their own right, while we do not even know the names of others. The builders of the Round Table, though not as chivalrous as its knights, deserve their own tale.

St. Gildas—the contemporary

We hear of Arthur’s greatest battle—Mons Badonicus or Badon Hill—before we hear of Arthur himself. St. Gildas, a Welsh monk of the sixth century, mentions the battle near the end of his De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (The Overthrow and Conquest of Britain). Written in Latin, this brief jeremiad is a shout of anguish from the blackest period of the Dark Ages.

Gildas was born in the old Celtic kingdom of Alt Clut, on the English-Scottish border, and was educated at the monastic college at Llantwit Major on the south coast of Wales. He seems to have been a man of high standing in the church, for he visited Rome and Ravenna and was called to Ireland to restore church order. His opinion of his native Britons was not high:

For it has always been a custom with our nation, as it is at present, to be impotent in repelling foreign foes, but bold and invincible in raising civil war, and bearing the burdens of their offences: they are impotent, I say, in following the standard of peace and truth, but bold in wickedness and falsehood.2

Nonetheless he felt his native country was important enough to write about, and the greater part of De Excidio is an outline of British history from the Roman conquest through his own era. Indeed, much of what we know of early Britain is from Gildas’s brief outline.

A part of the Roman Empire for over four hundred years, Great Britain saw its legions reduced in the fourth century to fight barbaric invasions in Gaul and elsewhere. By 410 Rome was telling the Britons to look for their own defenses against the raiding Scots and Picts. A series of local Roman tyrants filled the power vacuum; one of them, Vortigern, made the mistake of inviting the Saxons to settle in Kent to help ward off the Picts. The Saxons soon rebelled and invited other Saxons across the water to join them. The whole country was in upheaval, and pleas to Rome (in Gildas’s words, “the groans of the Britons”) went unanswered. “Thus foreign calamities were augmented by domestic feuds; so that the whole country was entirely destitute of provisions, save such as could be procured in the chase.”

Then somehow, someway, they turned the tide. Ambrosius Aurelianus led the remnant of the Roman cavalry against the Saxon infantry and succeeded.

After this, sometimes our countrymen, sometimes the enemy, won the field, to the end that our Lord might in this land try after his accustomed manner these his Israelites, whether they loved him or not, until the year of the siege of Mons Badonicus, when took place also the last almost, though not the least slaughter of our cruel foes...

Gildas informs us that he was born the same year as Badon Hill, and it is possible that he knew and even had dealings with Arthur—of whom, however, he makes no mention in his chronicle.

Perhaps we should not be surprised at the omission. Gildas explains at the beginning of De Excidio that “the subject of my complaint is the general destruction of every thing that is good, and the general growth of evil throughout the land...” He adds: “...it is my present purpose to relate the deeds of an indolent and slothful race, rather than the exploits of those who have been valiant in the field.” Arthur—or whatever war leader or high king was holding the Britons together during Gildas’s lifetime—may have seemed too recent a figure to write about, or Gildas may have bore him a grudge. A hagiography of St. Gildas written by Caradoc of Llancarfan in the 12th century tells how Gildas intervened when Guenevere was abducted by a certain King Melwas of the “Summer Country”. Caradoc also claims that two of Gildas’s brothers rose up against Arthur while the saint was in Ireland, and that Arthur killed the eldest.

One could wish that our good saint had taken up less parchment quoting Biblical passages, and devoted more time to describing the life and conditions surrounding him in this worldly realm. But we must accept him as he is—a lonely voice from Arthur’s own kingdom, cranky and fatalistic, a bleak personage from a bleak era.

Gildas eventually forsook Britain, founding a monastery on the island of Rhuys in Brittany (many Celts had fled to Brittany during the Saxon invasions). It is recorded that after his death, he was placed in a boat and allowed to drift; the boat was found in a creek three months later, with the body still intact. And so St. Gildas imitated the legendary Arthur, in death if not in life.

Nennius and Taliesin—Arthur comes to life

In the end, the Saxons did prevail. By the sixth century, the Saxons and their allies, the Angles and Jutes, had set up their kingdoms throughout most of England, though Wales remained free. It is among the Welsh that we find the earliest mention of Arthur. Whether he was indeed the war leader of Mons Badonicus, a different king, or even a minor deity from Welsh mythology, is an open question. He seems to have been a well known personage in oral tradition, for there are references to him in old Welsh poetry and prose tales such as Culhwch and Olwen. The first mention in a historical context is in the Latin text of the Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons), attributed to a ninth century monk named Nennius who lived in and around Powys, Wales.

The Historia Brittonum is probably a compilation of older material, to which Nennius added the prologue around 830. Gildas was likely his chief source, but he lists other materials as well, including monuments and “the histories of the Scots and Saxons, although our enemies.” Modest about his own talents, Nennius explains how he had taken up the pen of a chronicler:

But I bore about with me an inward wound, and I was indignant, that the name of my own people, formerly famous and distinguished, should sink into oblivion, and like smoke be dissipated.

His text covers Roman Britain and the age of the tyrants, in which Vortigern and St. Germanus figure largely. Near the end there is a brief mention of Arthur:

Then it was, that the magnanimous Arthur, with all the kings and military force of Britain, fought against the Saxons. And though there were many more noble than himself, yet he was twelve times chosen their commander, and was as often conqueror.

The Historia Brittonum goes on to list the twelve great battles that Arthur won, ending in Mons Badonicus:

The twelfth was a most severe contest, when Arthur penetrated to the hill of Badon. In this engagement, nine hundred and forty fell by his hand alone, no one but the Lord affording him assistance.

And so in the beginning there is only Arthur, standing alone—a great war leader, though not necessarily a king.

That such a commander would become the stuff of myth and legend is not surprising, and when we turn from history to Welsh poetry, we find the figure of Arthur has taken on otherworldly raiment. In the curious "Pa gur yv y porthaur?" (“What man is the porter?”) he appears at the gate of a fortress with Kai and Bedivere, and in the 60-line “Preiddeu Annwyn” (“The Spoils of Annwyn”) we find Arthur leading his warriors on a raid in the otherworld (Annwyn):

And when we went with Arthur,

dolorous visit

except seven

none rose up

from the fortress of God’s Peak3

The poem is from The Book of Taliesin, a manuscript in Middle Welsh dating from the 14th century, but which includes poems from much earlier. Some of them, such as “The Spoils of Annwyn”, are attributed to Taliesin himself, a famous bard who lived as early as the late sixth century.

Like Nennius, Taliesin is a shadowy figure. He may have been a bard in the court of King Urien of Rheged (reigned late sixth century) for a section of poems in The Book of Taliesin praises Urien. Many legends grew up around Taliesin, and both he and King Urien were eventually inducted into Arthur’s court—Taliesin as a bard, and Urien as Arthur’s brother-in-law, king of the mythical land of Gore.

Bards like Taliesin retained an echo of the memory of Arthur, and wove a myth about him. In the 12th century that myth was to be channeled by a very different type of writer—an English bishop and master propagandist named Geoffrey.

Geoffrey of Monmouth—the myth-maker

Like Gildas and Nennius before him, Geoffrey of Monmouth was a churchman from Wales. He was born around 1100, not quite 40 years after William the Conqueror and his Normans staged history’s last great invasion of England. Geoffrey himself may have been of Breton stock, his parents followers of William—for Monmouth, his likely place of birth, had been in Norman hands by then. He may have served as a monk in a Benedictine priory in Monmouth, but his later life was almost certainly spent at Oxford, probably as a secular canon at St. George’s College. This is where his masterpiece, Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), would have been written. It was first published around 1136.

It is here that Arthur and his followers become something resembling the familiar legend. Merlin, Uther, Guenevere, Gawain, Mordred, and the sword Caliburn (Excalibur) enter the story, and many of the episodes central to the saga are introduced, such as the tale of how Arthur was conceived at Tintagel:

So the King lay that night with Igerne, for as he had beguiled her by the false likeness he had taken upon him, so he beguiled her also by the feigned discourses wherewith he did full artfully entertain her... And upon that same night was the most renowned Arthur conceived, that was not only famous in after years, but was well worthy of all the fame he did achieve by his surpassing prowess.4

Here also we learn for the first time of Mordred’s treachery and Arthur’s downfall after the Battle of Camlann:

Even the renowned King Arthur himself was wounded deadly, and was borne thence unto the island of Avalon for the healing of his wounds...

Geoffrey’s obvious source for Arthur was the Historia Brittonum of Nennius. However, not content with twelve battles and victory over the Saxons, he has Arthur invade Ireland, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Gaul, and then, to crown it all, defeat the Roman Emperor Lucius. These extended campaigns take up most of the Arthur chapters, although there is some brief treatment of Guenevere:

At last, when he had re-established the state of the whole country in its ancient dignity, he took unto him a wife born of a noble Roman family, Guenevere, who, brought up and nurtured in the household of Duke Cador, did surpass in beauty all the other dames of the island.

There is even a bit of early chivalry on display:

Presently the knights engage in a game on horseback, making show of fighting a battle whilst the dames and damsels looking on from the top of the walls, for whose sake the courtly knights make believe to be fighting, do cheer them on for the sake of seeing the better sport.

It’s engaging reading—the only problem is that Historia Regum Britanniae is billed as a history, and most of it (at least the parts concerning Arthur, and the other early British monarchs such as King Leir) is pure fabrication. Even readers in Geoffrey’s own time were not fooled. “Thus to make a delectable tune to your ear, history goes masking as fable,” wrote the poet Wace. However, it was for the most part accepted by contemporaries; Robert of Torigni and Henry of Huntingdon used Geoffrey’s manuscript as authentic history, and for centuries it formed part of England’s official story.

Why would Geoffrey of Monmouth, a high-ranking and respected cleric, concoct such stories? In his “Epistle Dedicatory” to the book Geoffrey explains that “Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, a man learned not only in the art of eloquence, but in the histories of foreign lands, offered me a certain most ancient book in the British language that did set forth the doings of” the kings of Britain. Such a book, however, most likely did not exist. Geoffrey’s motives might, instead, have been political. “Early in the twelfth century,” translator Ruth Harwood Cline explains, “the Normans, established on the British throne by conquest after their victory over the Saxons in 1066, welcomed literary works that supported their position by describing the brutal Saxon conquest of the Britons in the sixth century and the Britons’ valiant struggle to deter them.” It is quite possible that someone in Henry I’s regime requested a “history” from Geoffrey that glorified the role of Arthur and his victories over the Saxons. Or he may have rallied round the Norman cause of his own accord—he seems to have had a genuine interest in Welsh mythology. A later poem by Geoffrey, Vita Merlini, portrays Merlin as separate from the court of Arthur, and much closer to the Welsh original: a madman with a gift for divination, who, after witnessing the horrors of war, had fled to the woods to live alone. At any rate, Geoffrey of Monmouth was well rewarded for his inventions—he was made the Bishop of St. Asaph in 1152, a few years before his death.

Chrétien de Troyes—the Arthurian romance

Whatever Geoffrey’s intentions in writing it, Historia Regum Britanniae was a medieval bestseller—at least two hundred manuscript copies were known to exist in English, and it was translated into other languages as well. The poet Wace, born on the island of Jersey around 1100, wrote a verse translation called the Roman de Brut in Old Norman (a dialect of Old French), adding fanciful details to Geoffrey’s story, such as the Round Table. It is probably through Wace that a trouvère in the court of Marie of Champagne named Chrétien de Troyes first learned of Arthur’s legend.

Chrétien was apparently born in Troyes and had clerical training, for his early work included verse adaptations of two tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Trouvères were an elite class of poet; they did not have to wander like lowly minstrels, but lived at a court under the patronage of one of the great nobles. Chrétien’s place in the entourage of Marie, the daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine and husband of Henry, count of Champagne, put him in one of the brightest and most literary courts in Europe. The fashionable subject of “courtly love”—a heady mix of Ovid’s playful Cupid and the Arabic love poetry coming out of Spain—was a favorite of Marie’s, and a recurring theme in Chrétien’s mature romances: Erec and Enide, Cligés, Yvain; or, The Knight with the Lion, Lancelot; or, The Knight of the Cart, and Perceval; The Story of the Grail.

All five of these poems are set in the court of King Arthur. Of particular interest are Lancelot and Perceval. In the former we find the first mention of Lancelot and his romance with Guenevere; and in the latter the first mention of Perceval and the grail, though it is not the Holy Grail. Like Ovid, Chrétien is a playful and sometimes sarcastic narrator. It is clear that his romances are not at all to be taken as serious history, but rather diversions for the court. The action typically only follows a few characters and is compact and well structured—a feature which leads some literary critics to see in Chrétien a precursor to the modern novel.

Lancelot, written around 1170, describes the abduction of Guenevere (first introduced by Caradoc’s life of St. Gildas) and her rescue from clutches of the villain Meleagant by Lancelot:

“Dwarf,” he said, “if my lady queen

passed by this place and you have seen

then for the love of Heaven, tell.”

The low-born dwarf, despicable

not wanting to give an account,

replied to him: “If you will mount

upon the cart that I am guiding,

by morning you may learn some tiding

about her and about her fate.”5

Lancelot does undergo the embarrassment of riding in the cart, his devotion to his lady triumphing over his pride. These and other tests prove that he is pure-hearted and loyal to Guenevere; in one chapter he even finds himself in bed with a naked woman (a situation the lady had ingeniously devised) but feels no desire for her.

Perceval is Chrétien’s last work, and may have been composed in the court Philip of Alsace, count of Flanders—for Marie retired from public life when her husband Henry died. He left it unfinished, and it was completed by other, less gifted poets. In Chrétien’s part, Perceval is a valiant knight who grows up in the wilderness and later comes to Arthur’s court. He rescues Blanchefleur and marries her; on a visit to his mother he meets the Fisher King, and this is where he sees the grail.

While Geoffrey and the Roman de Brut provided the background setting for Chrétien’s works, he did not seem much interested in battles, or in Arthur himself. Arthur is relegated to the role of the roi fainéant, or "do-nothing king," a beneficent but inert presence presiding over his court at Caerleon or Camelot (the first mention of Camelot, in passing, is in Lancelot). Instead, we have minor but beguiling incidents involving knights-errant and damsels in distress.

It is with Chrétien de Troyes that Arthurian legend begins to shift its balance from battles to romance, and from Arthur to his knights. He may have taken some of these from the Arthurian traditions of Brittany, brought over by Celts fleeing the Saxon invasion five centuries earlier. Others may have had no connection to Arthur at all. Lancelot, for example, may have been roughly based on Lancelin, the hero of a local folk tale.

The romans of Chrétien de Troyes were widely circulated in France and elsewhere, and other poets were quick to take up the subject of Arthurian legend. Marie de France made Arthur’s court the setting of Lanval, of one of her lais. In Germany, the minnesinger Wolfram von Eschenbach wrote a version of Perceval called Parzival, and Ulrich von Zatzikhoven's Lanzelet is based on Lancelot. French poet Robert de Boron reframed the grail story as a quest for the Holy Grail in his Josheph d’Arimathe. Even Dante, writing a century later, praised Chrétien for having made France the leading nation in narrative poetry.

Sir Thomas Malory—forging the canon

Arthurian romances in the style of Chrétien, such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, were highly popular in the 13th and 14th centuries. They even had an influence back in Wales, where, for example, Erec and Enide was the basis for the Welsh Geraint and Enid. Thus the legend of Arthur came full circle.

With all the new romances, there arose a desire to consolidate material and form it into a coherent whole. The result was the Vulgate Cycle (1210-1230), also known as the Lancelot-Grail cycle—a sprawling work in Old French prose that connected all the stories of Arthur and his court. John Conlee notes that the Vulgate Cycle “reflected two important attributes that set it apart from Chrétien and the writers influenced by him. For the sequence of works in the Vulgate Cycle were presented as being historical works, not romances, and at their center they possessed a serious religious purpose.” It also put the finishing touches on the Arthurian legend we are familiar with. Camelot has become Arthur’s main court, and a section has been added involving Arthur’s youth, including the sword in the stone episode, his receiving Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, the tale of Balan, and Morgana’s plot against Arthur. These details were mainly assembled from a now-lost work on Merlin by Robert de Boron.

The Vulgate Cycle was followed by the Post-Vulgate Cycle (1230-1240), which de-emphasizes the Lancelot-Guenevere romance and highlights the Holy Grail quest. It also incorporates the previously independent legend of Tristan and Iseult, making Tristan a knight of the Round Table.

Most of this literature was not, however, translated to English—which may explain why there are no references to Arthur in Chaucer. That work happened in the 1400s, and the translator was an English knight named Sir Thomas Malory.

Scholars are not entirely sure of his identity—there were several Thomas Malorys living in the early 1400s—but the most likely candidate is a Sir Thomas Malory of Winwick, a professional soldier and knight who saw action at Calais. An aristocrat of some standing (he served in Parliament twice) Malory nonetheless appears to have been a blackguard of the lowest character. He was in prison on several occasions, for various crimes committed by him and his lackeys. Kidnapping the Duke of Buckingham. Robbing Hugh Smyth’s house and raping his wife. Highway robbery. Stealing horses. The list goes on and on.

It was probably during one of his prison stays in the 1450s—at Marshalsea or Newgate—that Malory wrote Le Morte d’Arthur. His chief source appears to have been the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate Cycles (the “French book” he often refers to), but it seems he had also read Middle English poems such as the Alliterative Morte Arthure, based on Wace’s version of Geoffrey, and the Stanzaic Morte Arthur, treating the romance of Lancelot and Guenevere. Malory’s work is mostly a compilation, though he seems to have added some parts himself, notably the tale of Beaumains (Gareth). A stately, stoic, monumental work originally titled The Whole Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, Le Morte d’Arthur weighs in at 938 pages in my Modern Library edition.6 It lacks the playfulness and finesse of the French romances, while still trying to encompass them; the result is endless wanderings of knights-errant, and countless joustings, melees, and maidens abducted. When covering the signal points of the legend, however, Malory does possess a rough lyricism:

It befell in the days of Uther Pendragon, when he was king of all England, and so reigned, that there was a mighty duke in Cornwall that held war against him long time.

Much of Sir Thomas’s book is serious and matter-of-fact, at times even dull, and all the knights jockeying for position—Sirs Launcelot, Tristram, Palomides, Gawain, Gareth, Tor, Lamorak, Galahad and the rest—too closely resemble athletes losing their temper on the playing field.

With this came in Sir Tristram with his black shield, and anon he jousted with Sir Palomides, and there by fine force Sir Tristram smote Sir Palomides over his horse’s croup. Then King Arthur cried: Knight with the Black Shield, make thee ready to me, and in this same wise Tristram smote King Arthur.

Yet a subtle thread of fatalism runs through it, and most of the characters in Le Morte d’Arthur orchestrate their own undoing—a knight cannot serve both his lady and his lord; he cannot be true to both his family and his king. At times there is even a sense of revelation, and one can see why the book is considered a masterpiece of the late Middle Ages. Take, for instance, Lancelot’s reaction when the corpse of the Maid of Astolat is found in her death-barge on the Thames:

And when Sir Launcelot heard it word by word, he said: My lord Arthur, wit ye well I am right heavy of the death of this fair damosel ... Ye might have shewed her, said the queen, some bounty and gentleness that might have preserved her life. Madam, said Sir Launcelot, she would none other ways be answered but that she would be my wife, outher else my paramour ... For madam, said Sir Launcelot, I love not to be constrained to love; for love must arise of the heart, and not by no constraint. This is truth, said the king, and many knight’s love is free in himself, and never will be bounden, for where he is bounden he looseth himself.

In retrospect, Malory might owe his fame and his central position in the Arthurian saga simply to good timing. He was the first one to translate the Vulgate Cycles into English, and he wrote Le Morte d’Arthur just before William Caxton set up the first printing press in England. How Caxton got ahold of Malory’s copy, or if any payment was exchanged, is unknown. Caxton says in his preface to the book that he “enprised to imprint a book of the noble histories of the said King Arthur, and of certain of his knights, after a copy unto me delivered, which copy Sir Tomas Malorye did take out of certain books of French and reduced it into English.” Sir Thomas Malory died, it is thought, around 1471, and as the book was not in print until 1485 it is possible that the two men never met. Ironically Malory, the career criminal, had a grandson named Nicholas who was appointed High Sheriff in 1502.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson—Arthurian revival

In the 16th century, interest in Arthurian legend waned—1634 saw the last printing of Le Morte d’Arthur for nearly 200 years. The Renaissance and the Age of Reason had little use for dusty legends of medieval kings. Instead they drew on Classical subjects and the stories of the Bible and Greek mythology. There is nary a mention of Arthur in Shakespeare, though he did use another one of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s creations, King Leir, for a tragedy.

Arthur was not forgotten, but was employed more as allegory or satire, as in the folk tale of Tom Thumb (1621—adapted as a play by Henry Fielding in 1730), where Tom becomes a dwarf in King Arthur’s court.

With the Romantics’ rebellion against 18th century rationality and artifice, there rose a renewed interest in medievalism. The magic, sentiment and adventure of Arthurian legend lent itself to the brooding mood of the age. A new printing of Le Morte d’Arthur appeared in 1816, and Wordsworth’s “The Egyptian Maid” (1828) made use of the character Merlin and the quest for the Holy Grail. Still, Arthur and his retinue would probably have remained dim, half-remembered figures of the Middle Ages, like Roland or Piers Plowman, had it not been for the work of one man: Alfred Tennyson.

Born in 1809 to a Lincolnshire rector (he did not become a Lord until late in life, when Queen Victoria made him a peer) Tennyson began writing poetry at a young age. Sensitive and idealistic, he idolized Byron. After graduating from Cambridge in 1828, he and his friend Arthur Hallam went to Spain to join the rebellion against Ferdinand VII. But financial difficulties, the mental illness of three of his brothers (he was the fourth of 12 children) and the poor reception of his earlier poems cast a shadow over his youth. Hallam’s unexpected death in 1833 came as a further shock, but out of the tragedy he erected his masterpiece, In Memoriam. Its enthusiastic reception vaulted Tennyson to the forefront of Victorian poetry, and on Wordsworth’s death in 1850 he was made poet laureate. That same year he married Emily Sarah Selwood, and the remainder of his life went more or less smoothly.

Tennyson’s fascination with Arthurian legend is evident from his early years—“The Lady of Shalott” dates from 1832—and he even took lodgings in Caerleon, at the Hanbury Arms pub, while writing “Morte d’Arthur” in the 1830s. But it was in his years as poet laureate that he wrote most of Idylls of the King, a series of narrative poems about Arthur and his knights based on Malory. Written in Tennyson’s sonorous, elevated style in blank iambic pentameter, each of the Idylls can stand on its own; yet weaving through the whole is the character of Arthur, the grand Victorian image of a civilized king, ruling an empire with wisdom and justice:

For many a petty king ere Arthur came

Ruled in this isle and, ever waging war

Each upon other, wasted all the land;

And still from time to time the heathen host

Swarm’d over-seas, and harried what was left.

And so there grew great tracts of wilderness,

Wherein the beast was ever more and more,

But man was less and less, till Arthur came.

Taken together, Idylls of the King forms a sort of national epic. Written at the height of the British Empire, it acted as a balm to many of the anxieties of the Victorian gentleman: labor unrest, colonial turmoil, women’s suffrage, the advance of science, the crowding of cities and the decline of agrarian society. Arthur and his knights represent the sceptered race, born to rule. They have no need to earn a living and no desire to enjoy the comforts of modern life. Only by their bravery, honor and ideals is the kingdom (or empire) held together. In his epistle “To the Queen”, which finishes Idylls of the King, Tennyson seems to be speaking to his whole generation:

Is this the tone of empire? here the faith

That made us rulers? this, indeed, her voice

And meaning whom the roar of Hougoumont

Left mightiest of all peoples under heaven?

What shock has fool’d her since, that she should speak

So feebly? wealthier—wealthier—hour by hour!

The voice of Britain, or a sinking land,

Some third-rate isle half-lost among her seas?

The passing of Arthur and collapse of his kingdom paralleled what the Victorians saw as the sinking away of their England beneath the noise and commercialization of modern industry.

The first set of Idylls, published in 1859, sold 10,000 copies in the first week. Expanded editions were published in the 1870s and ‘80s, launching what became a full-scale Arthurian revival. Reworkings of the Arthur legend in novel form, such as Sidney Lanier’s The Boy’s King Arthur (1880), quickly appeared, and both Thomas Hardy and John Masefield composed Arthurian plays. Painters such as William Morris depicted scenes from Morte d’Arthur, and Wagner wrote operas around the stories of Tristan (Tristan und Isolt) and the quest for the Holy Grail (Parsifal). Unable to refrain from poking fun at the Arthurian fad, Mark Twain came out with A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court in 18897. Twain’s humor aside, the late 19th century polished the image of Camelot, highlighting the pure ideals of Arthur’s reign, and introducing a note of triste sentiment.

In 1937 a young writer named T.H. White, living in a “feral state” in a workman’s cottage, started reading Malory out of boredom. He loved it so much that he wrote a prequel of sorts to Le Morte d’Arthur, The Sword in the Stone (published 1938). Dealing with Arthur’s childhood and his tutelage by Merlin, it became a children’s classic. White subsequently wrote three other novels continuing his hero’s story, giving the whole work the title The Once and Future King. Also notable in the 20th century was novelist Mary Stewart’s Merlin trilogy, starting with The Crystal Cave in 1970, and Marion Zimmer Bradley’s revisionist The Mists of Avalon, about the women behind Arthur’s reign.

Recently there has been a trend to return to the roots of the “real” Arthur, as in Rosemary Sutcliff’s Sword at Sunset and the 2004 Clive Owen film King Arthur. Lacking his robes of myth and legend, however, the realistic Arthur seems to fall flat. More successful have been films based on Malory or his followers—Disney’s animated version of The Sword in the Stone (1963), the Lerner-Loewe musical and subsequent movie Camelot (1967), and, above all, Boorman’s dark fantasy classic Excalibur, where Wagner’s music and Nicol Williamson’s masterful portrayal of Merlin introduced Malory to a new audience. From here, it is likely that the legend will continue to grow and evolve. For if in Arthur we hear faint echoings from our past, we also glimpse the possibility of a brighter future.

1 I agree with Caxton who, in his preface to Le Morte d’Arthur, asserted that a real King Arthur had lived, but added, “...for to pass the time this book shall be pleasant to read in, but for to give faith and believe that all is true that is contained herein, ye be at your liberty...”

2 Translation of De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae and Historia Brittonum by J.A. Giles.

3 Translation by Sarah Higley.

4 Translated by Sebastian Evans.

5 Translated by Ruth Harwood Cline.

6 Malory’s Middle English is actually easier to read than Chaucer or Shakespeare, and I recommend reading him in his original. Translations into modern English, such as the one by Keith Baines, quickly become monotonous. Also avoid, at all costs, abridged versions, such as the Winchester Manuscript version published by Oxford University Press—just when an adventure becomes intriguing, it’s interrupted by a gloss.

7 The preeminent Arthurian satire of the 20th century is, of course, Monty Python and the Holy Grail.