|

WHISTLING SHADE |

(Florida Academic Press)

A blurb on the back cover of Twice a False Messiah claims it has the “energy’’ of Raiders of the Lost Ark. In fact, Messiah aims to be a more spiritual, contemplative, Raiders. The quest in Raiders, however, was for a material object, described in the Bible in some detail. By contrast, the quest in Messiah is for a word, one that is explicitly not written anywhere, a word thought to have been heard only a few times, ages ago, by Biblical A-listers such as Abraham and Moses, that word being nothing less than the True Name of God. Based on certain Old Testament passages, Messiah’s two-man team of protagonists believes there is such a name and that they can figure out what it is.

Their conceit is that if a “righteous man’’ shouts God’s true name at the right time and place, one effect will be to heal the age-old rift between the descendants of Abraham’s two sons, Isaac (the Jews) and Ishmael (the Arabs). This, in turn, should lead to World Peace (the state of being, not the Lakers forward).

Narrator Dexter Doyle, a veteran globe-trotter at 28, has had adventures such as Bible-smuggling behind the Iron Curtain and surviving a metaphysical attack by witches, leaving him both cynical and thirsting for a greater connection to the spiritual. After a chance encounter at an Athens café with self-styled wanderer, philosopher and expert on Hebrew and Egyptian history Joachim Kline (whose usual dress is Hawaiian shirts and coveralls), Doyle agrees to be his assistant searcher for the True Name. Or was their meeting a chance encounter? Kline says—repeatedly—”There are no coincidences,” a rather broad statement.

A further premise is that Moses, adopted as a child by the Pharaoh's daughter, influenced the Egyptian royalty with his monotheism, leading eventually to Pharaoh Akhenaton’s worship of the sun as a symbol of the one true God. Akhenaton, in turn, may have left clues to the Name in tombs and statuary, but those clues have been chiseled away by later Pharaohs, making the work of Messiah’s protagonists difficult and, unfortunately, rather tedious.

One clue in the search for the Name are the letters YHWH from the Hebrew tradition that led to the substitute word Yahweh (Jehovah). Other promising leads come from a 700-year-old map, an old Coptic monk, and Doyle’s mysterious repeating dream, which features a beautiful and somehow familiar woman. After the dream recurs he realizes she resembles an Egyptian princess he’s seen in ancient carvings. Oddly, Doyle must experience the dream another time or two before realizing the dream girl/princess also looks like his old girlfriend.

Messiah sports a diverse and well-drawn cast of secondary characters, including Doyle’s old girlfriend, who turns up unexpectedly, reporting mysterious dreams of her own. There is some sleuthing through museums and ancient tombs and plenty of red herrings. But there’s little sense of danger beyond what Kline believes will be a nasty fate for the world if his quest fails.

Aside from its unlikely premise, the book’s key difficulty is that the occasional spikes of excitement over a found clue or a strange experience are separated by long sweat-stained days and uncomfortable nights waiting at tiny tea stands or grimy hotels for the next excruciating riverboat or train trip south from Cairo to Khartoum.

Ironically, describing these interregnums is where Gabriel’s writing is at its best. On one seemingly endless train ride across the desert we feel the constant baking heat, the omnipresent grit in our clothes and teeth, feel every lurch, jolt and bump, and we gag on every foul odor infesting the packed third-class carriage.

The flat pan of sand stretched off to the horizon where clumps of rocks like blackened dirt-mountains shimmered in the watery haze of mirage. The foreground’s emptiness was broken only by a brave string of telephone poles and the occasional bones and carcass of a camel long deceased. Life, such as it was, existed in the swooping shadows cast by prowling vultures.

My head bounced steadily against the pillowed sweater on my window ledge. The train rolled on.

The story is set in 1978, when “a spiritual trembling (is) abroad in the world,’’ a time of mass suicide and murder at Jonestown; the death of two popes within weeks of each other; the Shah of Iran resisting abdication; and millions waiting to see if Egypt and Israel will sign a peace accord or clash yet again. The challenge of writing suspenseful fiction about the possibility of global peace arriving at a specific point in the recent past is that we know, unfortunately, that it didn’t happen.

- Brian R. Bland

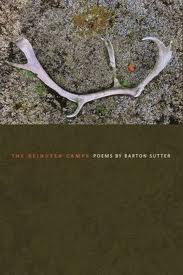

The notion that rhyme and meter are somehow old-fashioned has now itself become old-fashioned. However, these two weapons in the poet’s arsenal are still widely avoided—perhaps because they are so difficult to wield with grace. And for this alone we owe Barton Sutter thanks; he is, at least, trying.

In his latest work, The Reindeer Camps, Duluth’s Poet Laureate delivers poems in various sizes and styles, most with a form and some kind of rhyming flourish. A rustic versifier who seems only a hop-skip away from the 19th century, Sutter is nonetheless able to sidestep the soggy Victorian pablum that damned rhyme/meter in the first place. His narrative poems are objectively told, and even the melodramatic story of “The Snowlady”, about a woman leaving her abusive husband, is told with a curious, boyish detachment. Sentiment, when it does visit a poem, has an A.E. Houseman sort of obliqueness—as in the last stanza of “My Mother at Swan Lake”, a memory of a family picnic held while his mother was in cancer remission:

My mother leans against a tree.

She sighs. I hear her say

Across the half a century,

“It’s been a lovely day.”

More often, Sutter seems like Minnesota’s answer to Robert Frost, the older Frost who was blunt and good-humored and really didn’t care if he was with the times or not. He can sketch nature with the same effortless ease, only in this case the topography is northern Minnesota. From “How to Say North”:

Nothing says north like a white pine

Unless it’s a maple gone red to maroon

Except for the way cedars lean from the shoreline

Nothing says north like a white pine

But birches so bright that they shout about sunshine

But while Frost saw deeply into things, Sutter’s poems mostly skim the surface, providing quick glimpses of a variety of subjects. The seven sections of the book cover memories of childhood, nature (including pets), political poems (fans of George W. Bush—if any poetry readers are fans of George W. Bush—might want to skip that section), Minnesota culture, literature, and a section of personal poems that ends with the unexpectedly romantic “With You in Spain”. The title poem takes up the whole last section, and is not about Barton Sutter at all, or even about Minnesota. “The Reindeer Camps” is based on Piers Vitebsk’s book The Reindeer People, about the nomadic Eveny people of Siberia. Heavy in trochaic feet, the poems recalls The Song of Hiawatha, but is more anthropological than mythical:

Come, let us bell the deer,

Just our leaders, gelded males.

I think that we have several here

To hang around their necks,

Fashioned from condensed milk cans

With spoons tied in to clang

Of course, when playing tennis with a net the ball can go astray, and the perfect rhyme or phrase are sometimes lacking in Sutter’s poetry. “The Pileated Woodpecker”, for example, begins with the childish

Is black and jumbo, like a crow

Whenever I spot one, I go, ‘Oh!’

but ends with the pirouetting couplet

So it’s possible that we’re related

me and the pileated.

Truth be told, Sutter is silly as often as he is sagacious. Yet uneven though it might be, The Reindeer Camps is not a volume that seems likely to meet the fate prophesied in “The Bone Yard”:

So I would urge young poets worth their salt

To find a bookstore dim with dust and grime

And sit each week among the dumb results

Of poets, often famous in their time,

Whose work has somehow turned unreadable.

They, too, believed in metaphor and rhyme.