|

WHISTLING SHADE |

Man, I feel like I dodged a bullet," Max says to me as we drive home after meeting his birth mother.

"Yeah," I say. "Thank you for doing that. I know you only did it to make me happy. I appreciate it."

He raises an eyebrow, smiles at me. "Expect greatness!" he says. "I'm an athlete!" That's what he says instead of "Ah, shucks."

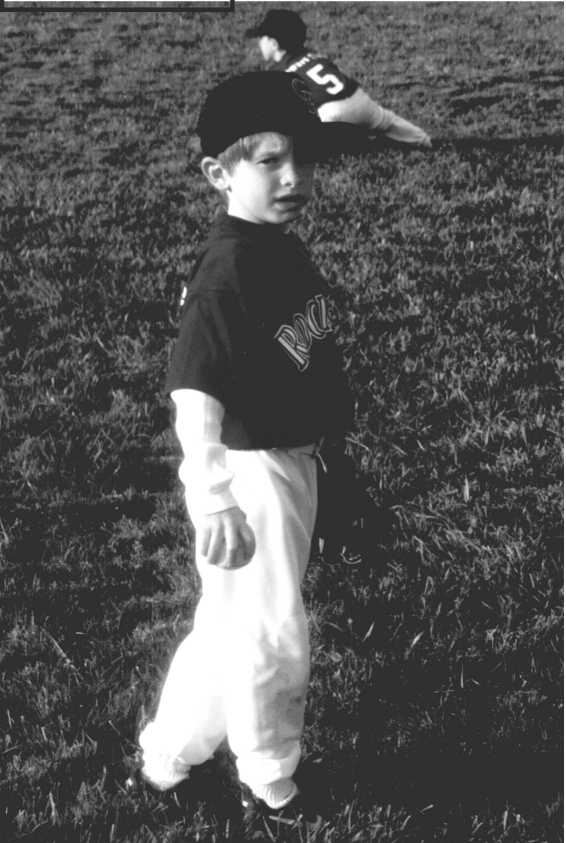

Max is my son, 18 years old and, in some ways, the hardest of all my kids to raise. I usually describe him as red-haired and freckled, like Tigger on speed, or a hyperactive chipmunk. And he was that. He still is. One doesn't outgrow ADHD. But there was more.

Max knew by the time he was two, that the world's a dangerous place. He'd been exposed to drugs and alcohol in utero, abused and neglected after he was born. Then he bounced around in foster care. When I met him, the week he turned two, he had what a lot of adoptive parents call the "foster care look." Thin scraggly hair, pale greyish skin, thrift-store cast-off clothes, too small shoes, empty eyes. Everything he owned filled a garbage bag. There was nothing worth keeping.

One night I found Max sitting in front of the refrigerator, door propped open, surrounded by food and eating raw eggs. He hoarded food, hid cookies under his pillow, crackers and juice boxes under his bed, leftovers from the refrigerator in his closet. He fed baby carrots to the VCR because, he told me, it was hungry.

Worse things than hunger had happened to Max, things that didn't show up until he was older. Max's birth parents were both methamphetamine addicts. Meth addiction means that parents are awake and paranoid and hyper-sexual for days, and then they sleep, for days. They don't wake up when babies cry. They become sexual predators, and, like malevolent magnets, they attract them, too.

Max's birth mom has AIDS and, more important, Hepatitis C. There is no cure for either, but Hep C is a surer, swifter death sentence. She's stayed clean and sober since she lost Max, and she's been working with AIDS patients. She's done well—a rare success story in the world of Childrens' Protective Services. Max isn't interested in his birth family, but I want him to meet her because I'm afraid that one day he might want to, and by then, it could be too late.

So, we set up a dinner. We meet at a nice restaurant, a steakhouse my brother owns, and Max is a little nervous—he's asked me to stay. His birth mother is very nervous. We're a little early, but she's there already. She's brought treasures for Max, a photo from when he was little, a piece of jewelry, a child's book, pictures of his brothers, things she wants Max to know about. And she tells him about his two brothers. One, only a couple of years older than Max, works at a minimum wage job he hates, and lives in low income housing with his girlfriend. She has a two-year-old boy by a different father and is 8 months pregnant. The other brother is in jail.

I see Max scan his mother. She has the acne scars of meth addicts, missing teeth, broken, cracked fingernails and she looks twenty years older than she is. She's come to dinner on her Harley. She's lost contact with Max's birth father, but tells him about her latest boyfriend, someone she met at Narcotics Anonymous.

We visit for an hour or two. Max asks polite questions and is charming and warm to his birth mom. On the way to our car, he hands me the things that she brought. "You should hang on to these for me," he says.

As we drive home, I reach out to brush his hair away from his forehead with my hand, squeeze the back of his neck, touch his hand. "Your mom was very happy to see you," I say. "Yeah," he says. Then, "I want to say something. Don't call her my mom. You're my mom. I have all the family I want already." I swallow, blink back tears. We drive in silence for a while, listening to country music on the radio.

"I love you, Max," I say, when I can finally talk.

"Love you, too, Mom," he replies, gazing out the window at cars rushing by. Then, "Expect greatness! I'm an athlete!" he says to me with a small crooked smile.