|

WHISTLING SHADE |

Inside the cuff of my dream, within this sluggish consciousness like a muddy river, words release into my ear: ‘What a singular moment is the first one, when you have hardly begun to recollect yourself, after starting from midnight slumber.’

The church clock strikes with heavy clangs. One, two, three …‘the dead are lying in their cold shrouds and narrow coffins’ … four, five, six … ‘yesterday has already vanished among the shadows of the past’ … seven, eight, nine… ‘tomorrow has not yet emerged from the future.’ The seconds pass into a deep quiet. How pleasant the solitude: the rise and fall of my own warm breath beneath the covers, curling me back into that soft space. A distant knock dissipates the last fragments of sleep.

“Mr. Fane? Sir, breakfast is here.”

Now I am irrevocably awake. I bolt up, focusing my thoughts on the reality of the day. I had arranged for room service to deliver my breakfast at nine o’clock, after my morning shower. I glance at my electrical equipment: cell phone, laptop, three trifield meters all charged and ready. I tie on my robe, rake down my hair, and open the door.

“Good morning, sir,” the housemaid says, dressed in a costume of long dress with a white apron and lace cap.

The Colonial Inn is famous for their authentic 19-century style and service. To me, it’s an irresistible accommodation—I guess I was born in the wrong era. From the minute I walked through the doorway of the Inn, I inhaled sweetness from the old blue-washed walls behind the Front Desk. Why it was a familiar scent (violet soap?), I can’t explain. Of course the walls were not blue at all. Modern paneling surrounded the Front Desk and entrance. I saw that clearly, but the aroma and image remained wedged in my head for hours.

The maid holds up a tray. “My name is Alice. May I set your breakfast down?”

“Thank you, Alice.” I recall now dreaming of words on a page, a singular voice, something about yesterday … tomorrow emerges. My late night readings repeated in my mind, no doubt.

The maid steps inside. “And did Mr. Fane sleep well in Room 24 last night?” She eyes me with a wink and tilt of her head. Her lace cap is now askew.

I do love it when women flirt with me. Unable to resist a smile, I put on my most formal Bostonian 1800s vernacular and say, “Most assuredly, Miss Alice. Not a single spirit disturbed my rest. No grim Mr. Emerson at the fireplace. No grayish shades of women floating on the ceiling, and not a single bump in the night. Unless of course it was the elevator.” I grin.

“You did not see Henry Thoreau scribbling away at the desk? We’ve had three guests last year report that one.”

“I slept like a babe.” I make a little gentlemen’s bow.

Alice laughs at my clumsy pose. My eyes follow her as she sets the tray on the table by the window. Steaming cornbread, a boiled egg, huckleberries and cream, and a pot of coffee. Did I order huckleberries?

“I expect, sir, such shadows held their breath last night and did not enter your bedchamber.”

Definitely flirting. “Really? And why not? Am I not worthy to be haunted?”

“Not everyone experiences Concord’s ghosts here. I suspect their apparitions are selective for each guest. Are you a believer?”

“I admit never having met a single ghost in my life, but I am certain they exist. Consciousness is energy, is it not? First Law of Thermodynamics: Energy can transform from one form to another, but it cannot die or be destroyed.”

“You are a scientist?”

I nearly laugh. “God, no.”

“Have a good day, Mr. Fane. The local weather is station 52 on cable,” she says with a little curtsey as she closes the door.

My cell phone buzzes and the ID flashes Cookie Beaumont, Institute of Perceptual Studies. The boss, and my wake-up call—30 minutes late.

“And good morning to you, Cookie. Is it 8:30 already?”

“So sorry, Edward. I overslept. It’s nine. If it wasn’t for those damn garbage trucks on First Avenue, I’d still be knocked out.”

I detect a breathy yawn as I pour myself coffee.

“So, there you are, in historic Concord. Are you loving it?”

“I am. And grateful that you didn’t book me in that dreadful B&B in Lexington, like last year.”

“I’m still learning about your tastes. Did you arrive terribly late? You’re not exhausted are you? I want you chipper for this investigation today.”

“I’m fine. Actually I sat up reading for a while. Familiarizing myself with the subject, so I get sturdy impressions. I don’t want any mishaps, like last time.”

“Familiarizing yourself with what exactly?”

“I want a stronger sense of Nathaniel Hawthorne before testing at the Old Manse. I sat by the fireplace and read his short stories. It was nearly midnight when I read The Haunted Mind, which I thought was about the hauntings he’d experienced. You know, Reverend Ripley at the Manse and Dr. Harris at the Atheneum Library?”

“It wasn’t?”

“Not at all. It’s more an exploration of being awake in the dream world. Pretty cool, actually.” I paused to gulp coffee. “Do you think Hawthorne is aware when we read his stories?”

“Is that a rhetorical question?”

“I suppose. Anyway, I couldn’t stop. Found myself paging to Night Sketches, Beneath an Umbrella about a man walking in the rain at night. And guess what? It’s raining this morning! How appropriate.”

“Oh my stars, you must be psychic.” She yawns again through the words.

The fact that Cookie thinks of me as a psychic and can joke about it is a bit unsettling. I don’t predict future events or hear voices from the dead, thankfully. And I prefer the title Assistant Investigator. My intuition isn’t more than a useful oddity in her world of technology. “Psychic? You’re hilarious, Cookie.”

“Yes, that’s why I’m the director. What time are you doing the Old Manse tour?”

“First tour is at 10:30.”

“Remember to be extra careful not to let the Manse tour guides see that you’re testing ley lines with the Gauss meter. They’ll toss you out on your ass before you get past the front parlor. Call me as soon as you get back and send the meter readings ASAP. George arrives in Concord tonight. He wants you to go with him tomorrow to Cape Cod. Did he call?”

George! The quintessential ley line hunter of the world—a know-it-all beyond endurance who is ridiculously skilled at tracking these invisible energy highways. “You want to investigate ley lines at Cape Cod?”

“We’re thinking if you get solid electromagnetic field readings at the Manse and can track them to the Cape, we’ll have the first leg of the Northeast magnetic energy grid. You know George found evidence of a ley line node in South Yarmouth, right?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Well, it’s not exactly the quality of the Great Pyramid ley lines, or the lines of force at Stonehenge, but, a small point on Long Pond scored above 4 milligauss for magnetic activity.”

“Four? That’s off the chart.”

“It’s a triumph! Why do you think I packed you off to Concord in such a rush? The Institute is counting on you to match George’s readings on the Cape to Concord’s. If those nodes hook up, we’ll track the line northwest to intersect at what is likely the vortex at Mt. Greylock. I’ll be sitting on the edge of my chair all day.”

“I know I’m still new to this, Cookie, and the Institute is only in Phase 1, but if or when we can confirm ley lines in Massachusetts, and even if we can track the energy highways to a triangular grid, what happens next?”

“Assuming my donations keep up, we’ll investigate to prove ley lines carry the imprints of past and future realms. And, that we can communicate and even transport within them.”

Prove? I shake my head. Cookie maintains these magnetic lines of past and future can be technologically verified. Nicola Tesla’s spin theories, subatomic particles, and quantum fields might as well be Chinese to me. I failed physics twice, so I take her word for it.

“And then, Edward, we attempt to test the vortex. But that would be Phase 2 and 3. You are planning on staying with us for the full program, right?”

She keeps testing me about quitting because my resume reveals I’ve been a quitter; my life runs somewhere between misfit and wanderer. “You mean stay on to investigate the vortex?”

“I recognize Gaussian beams and wave frequencies are not your strong suit. But your … sensitivities to magnetic fields, your brain surges, are highly useful for the Institute. You’re a living drowsing rod, Edward. That little trap door inside your head, I just love it.”

She may love it. I’m not so sure. “One thing still scares me.”

“Vile vortices? Relax, Edward. There are no negative time warps in Massachusetts. Not even a single dark energy sink that George could verify.”

“You don’t think Lizzie Borden’s house in Fall River is a vile vortex? That foul smell and the downward counter-clockwise spiral I felt? I could barely stand up. I shudder to think what would have happened if I had to be there for any length of time.”

“Yes, that field was disturbing, but hardly the Bermuda Triangle. No one has disappeared into a void in Fall River and no compasses have stopped working. The EMF activity present there is more likely a pocket of conscious spirits. If it connects to a ley line, we have yet to discover it. Right now there’s no evidence it’s part of the planetary grid system.”

Officially there are ten known vile vortices across the earth. All places where people, ships, and planes have disappeared. All ten are at equidistant geometric points, yet none found in the Northeast corridor. But there are always new discoveries, or so says Cookie.

“Get going with your day. And, Edward? Don’t forget your umbrella.”

I dive into my breakfast just as the cornbread fully absorbs the butter. While eating, I read over my notes on Hawthorne.

Hawthorne’s supernatural sensibilities showed up in so many of his stories. He claimed to see ghosts too (especially at the Old Manse in 1842). Because I had experienced a brain surge while standing inside the Old Manse last year on one of Cookie’s scouting expeditions of spiritual domains, she concluded that investigating magnetic fields in Massachusetts might prove worthy to determine ley lines there.

While my event at the Old Manse was significant, I lost the node of energy and could not locate it again to test further. Full of doubt and ready to quit these expeditions, I discussed my resignation with her. She refused. Little did I know she was planning to train me as a ley line hunter—known in the pseudoscientific world as earth grid travelers. Not a bad profession given my propensity for feeling energy flows inside the left side of my skull. More than a few times a Gauss meter verified my peculiar headaches, measuring the earth’s electromagnetic field around me at 2 or 3 milligauss. Discovering the vortices and tracking where these ley lines extend and intersect across the earth is the ultimate adventure. I just wasn’t sure it was truly my adventure.

‘Pleasant is a rainy winter’s day, within doors!’ Hawthorne writes in Under the Umbrella. This is July, but I agree anyway as I walk through hissing and sputtering rain the half a mile up Monument Street. With my hoisted umbrella, the black dome over my head is like my own dark cloud. Traffic noises fade away with every footstep on the dreary road. The raindrops are conspiring with puffs of wind against my face. I beat back a sense of shivering reluctance.

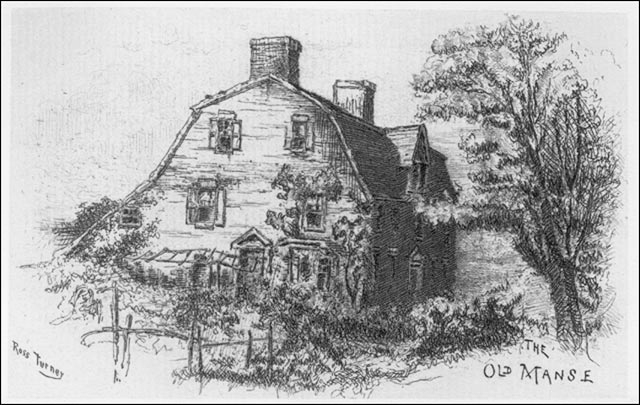

At the sight of the old parsonage, silent and grey among the black-ash trees, I get the slightest shift inside my skull. The trap door opening? The Manse’s dull facade looks as if some everlasting sadness has taken possession there. I press on.

My raincoat conceals my three trifield Gauss meters in the front pockets. No cell phone to interfere, no wristwatch to skew the EMF readings. I check the dials, settings, and battery levels. For a baseline, I pause beneath a power line and raise each meter up to confirm they are registering.

Leaving my umbrella at the side door of the Old Manse, I enter and purchase my ticket along with four other visitors. Darn, I was hoping for a bigger crowd. I didn’t want to get caught pointing the meters inside the house. Our tour guide is a venerable old dame with her hair in a bun, curly around the temples, and dressed in a full-length hoop skirt with a tattered, blue embroidered shawl. She might have doubled for Old Esther Dudley (gold cane and all), one of Hawthorne’s characters who believes she possesses talents to call forth the dead from a haunted mirror.

“I’m Ellen, and I’ve been doing tours here all my life,” she says in a quivering voice. “The Old Manse property, all this land has been inhabited for some 4000 years. Native Americans to the first English settler on the property, James Blood.” Here she grins with a sparkle in her blue eyes. “And I am the last living descendant of Master James Blood.”

Everyone ohhs and ahhs. She reminds me of winter with her withered white hair, parched skin, and ivory beads. I half expect cobwebs to gather under her chin. But there resides a faded magnificence in her manner as she displays her strait-laced, “whale-boned” bodice that women wore “in those days.” She refers to it as the cage, which gets me laughing. Two women in the group frown at me; clearly they do not think the cage is so amusing.

Ellen totters into the front parlor. Without losing a beat, she glides into her speech on the history of the Manse: the Emerson family to Reverend Ripley to the Hawthornes (doesn’t everybody know this stuff?). I hang at the back of the group to point each meter as we walk and pause. All three record zero EMFs on the dials. Above the piano is a portrait of Reverend Ezra Ripley, the reported resident ghost. Zero EMFs there, too.

Old Esther climbs the staircase, pausing at the half point. Between her dim eyesight and weary legs, we move slowly. But here comes my big moment—inside Hawthorne’s study at the back of the house. We pause at a stunning portrait of Hawthorne and I get that shift in my head again. Meter number one registers between zero and one. Meters two and three verify.

Most ley lines run five to six feet wide, but this weak energy field tells me this spot in the house might be a stray edge of a ley line.

“Emerson wrote his essay Nature in this room,” Old Esther says and points to the desk. Yeah, yeah, I move discreetly to the back window on the same spot where I experienced my previous brain surge. I position myself to anticipate a wave of dizziness.

Old Esther is chatting on about Hawthorne’s writing his Mosses from an Old Manse. The needle on meter one is at zero. My head is still clear. Not a single throb surfaces. Meters two and three undeniably verify no EMFs.

The view out the window is wavy from the rain. Odd I don’t feel anything. Maybe my position is off a few degrees. I move left, then right. Here comes Old Esther, so I stash the meter in my pocket. What is that look she’s giving me? Relax, smile it up. “Esther? Oh, sorry. I mean Ellen. Is it true that Emerson didn’t think much of Hawthorne’s writing?”

She takes the bait, going into a spiel about how Emerson didn’t appreciate Mr. Hawthorne’s talents as she leads us up the attic stairs to the garret. That’ll take ten minutes or so. I stay behind in the study. The rain is softer now. I stand in what I think is the ley line or node, directly by the window, and gaze out as I had done on my first visit. I recall scanning the back lawn. I focus on the beaten-down grass and dripping trees. My gaze follows the winding path to the Concord River and the Old North Bridge. Snap.

The room spins. The left side of my scalp begins to throb. Yikes, a devil’s hammer is striking my temple. Struggling, I check all three meters. Between zero and one.

“Young man,” Old Esther squeaks, “I insist you stay with the tour.”

I lean against the wall for a moment, hiding the meter in the fold of my raincoat, breathing through my mouth.

“Oh dear. I’m so sorry. Are you ill? I’ll call Security.”

“Just need some air.” In seconds, I’m stumbling down the staircase and out the door. My stomach cramps and I know this is the signal that relief is imminent. Once I’m out of range, the energy drains out of my head, the trap door closes, and I’m good as new.

Needing a breather, I sit on a wet bench beneath a black ash tree, umbrella opened, staring at the rivulets of water in the soil. Why didn’t the meters surge, like my head did? The probability of all three meters malfunctioning at the same moment is … not probable.

There’s a ley line here, a node or vein of magnetic energy; my body knows it!

Thinking hard, I review: I stood at the back window, saw the trees, lawn, river. My head surged. What had I experienced in the study that the meters had barely picked up? A split second passes. I want to hit myself in the head: I wasn’t standing in the ley line. I saw the ley line. Not literally, maybe, but did my brain somehow receive the magnetic frequencies from the visual? Maybe that’s what occurred on my first visit to Hawthorne’s study last year—I witnessed the ley line from the window, but lost the brain surge and couldn’t locate the energy again because I wasn’t looking at it.

Now what? I can’t go back to Cookie with this failure; she wants meter readings. She would advise me to walk the property to localize the disturbance within me. I take a minute to rest. I’m going to need it, especially if I have to endure another brain surge. I wonder if this trap door in my brain gets bigger with every event.

Near the bench is a garden full of blooms hanging with rain, which has now diminished to a steady drizzle. One of the roses lies broken on the grass. A bud actually, faintly red. I’m not sure why but I pick it up. I secure it in the buttonhole of my shirt and begin my walk to the back of the old parsonage property.

Hair dripping, shoes and socks soggy, I pace myself using meter number one. I observe Hawthorne’s boathouse and a replica of his Pond Lily tied at the dock. I walk the lawn, making angled tracks in hopes that I might catch a stray edge somewhere. My sense of drama takes over, and I imagine I’m following the gray footprints of the Reverends Emerson and Ripley, Hawthorne and his wife Sophia. Wasn’t there an apple orchard here once?

When I walk the riverbank, meter one is reading between zero and one, barely a hair to track. I test beneath the solemn boughs of the oaks and elms, their rustling leaves making sighs in my brain.

The stone walls remind me of musketry and battle smoke. Above the sleepy Concord River, I watch volleys of steam blow toward the Old North Bridge. Close by is a footpath along the eastern bank, and here the meter needle rises toward 1 milligauss.

The second I place my foot on the muddy path, I spy a woman standing on the bridge. In Manhattan, women are often caught in the rain without umbrellas, and there isn’t a finer way for a guy to meet a damsel in distress than offering her shelter under his umbrella. These chance encounters often turn into a date for a drink or coffee—or more intimate athletics. I hurry up the path with my trusty umbrella. The meter dial rises toward 2 milligauss. I feel another shift, that trap door opening wider now. I’m just a tad dizzy. Some kind of energy is floating in. No pain yet.

“Hello,” I yell, stumbling through the puddles. Finally I step onto the bridge entrance near the obelisk monument. She is standing dead center on the bridge.

What a thin little thing she is, her tiny waist so appealing. Her small hands neatly clasp the rail, almost child-like. Her head hangs low over her chest, so I can barely see her face for the wet hair stringing on her cheeks. I see she’s strait-laced and whale-boned like Old Esther, but her long white dress clings to her slim hips.

“Good afternoon. You must be one of the tour guides,” I say and extend my umbrella to cover her head, but I leave a respectable space between us. The woman lifts her face. Never in my life have I ever seen such heartsick eyes. The dark orbs resonate so deeply, I can hardly keep from looking away. Stifling a gasp, I attempt to smile. “Are you on your way to the old parsonage? I’m happy to escort you.” Her hands grip the rail as if a sudden wind might suddenly blow her over the side.

She returns her vision to the water below.

Is she shy or have I rudely intruded? My attraction to shy women is practically legendary—something about the challenge of engaging them in conversation; it’s such a win to make them laugh. “Well, it’s certainly a miserable day, but surely a cup of coffee and indulgent dessert will help. I love chocolate cake on rainy days. Would you like to join me?”

She is transfixed on the river. The current moves remarkably slow as if trying to delay time. My temples are drumming. Her silence is clearly a no. So, I watch the river with her for a moment, my arm tipping the umbrella to protect her more than me. I wonder if the rain soothes her like it does me: the tapping, the rhythms, the soft puckering of the tiny waves.

“The water at the bottom is murky,” she offers. “There is slime there.”

“I suppose. I don’t really know, I’m a visitor here working on an investi—project. What do you do?”

“Teacher.”

“Oh, a fine profession. I dropped out of college some years ago. I’m experimenting with different jobs. I’ll bet you’re a wonderful teacher.”

“Not at all.”

“Oh come on. Your students probably adore you.”

“Doubtful. Children require a teacher with a cheerful nature to inspire them. I have no such gift.”

I’m at a loss for words. Her hands still grip the rail so tightly her fingers look like veined marble. A lace hanky is stuffed into the cuff of her sleeve. No rings. No jewelry at all. “Do you live around here?”

“My family lives on the farm on Punkatasset Hill.”

Despite the sad eyes, this woman is a timid beauty. If her dark hair were dry, it would spread down to the small of her back. And I’ll bet she has small ankles and toes painted pink. “Please, may I escort you home? You’re soaked to the bone.”

Bravely, she fights off tears. “I cannot go home.”

Her touching reserve wins me over. I have this reckless desire to sweep her off the bridge, carry her into the Old Manse and place her before warm firelight. Absurd! Then I remember the rosebud. I remove it from my shirt’s buttonhole.

“I found this in the grass. I think it would look lovely in your hair.” If I had the courage I might have placed it at the side of her head, but that would be too bold. I offer it from my palm.

She does not take it.

I place it on the rail. After a moment she releases her left hand, takes the flower, and presses it to her mouth. “Oh, what a strong scent for such a young bud. You are most kind, sir, most kind. I thank you.”

“The pleasure is all mine. Oh, where are my manners? We haven’t properly met, have we? Edward Fane, from New York.” I put my hand out for a shake.

Still holding the rosebud in her left hand, she lets go of the rail with her right and a hint of a smile tries to emerge. “Martha Hunt.” She slips her hand into mine.

Wham! The sky flips. I gasp for air. My head is a jack hammer. I feel a cold burning penetrate my skull, and I’m tumbling out of control. The air is a screeching whistle inside my body. A black cowl takes me down, down, down, rolling me across the planks of the bridge.

I struggle to see through the dark gauze over me. My head is pounding. My throat and neck swell; even my stomach shakes. The wet planks scrape my face. I can hear the river and make out vague light as I focus my eyes. Half a moon breaks through the clouds and I stand up, using the rail to support my wobbly legs. Inhaling slowly, I calm myself. Below the bridge, on the grassy bank, I see a pair of old shoes and bonnet. Is that Martha’s hanky stuck in the mud?

Some cleavage in my brain urges me to dive into the river to find her, but just at that moment a flame on the river alerts me. I watch the light come closer through the night. No, this is not a flame but a boat lantern. The moon lights the hull and I recognize Hawthorne’s Pond Lily.

The earth slows its vibration inside my head; I am grateful. A bird calls from a tree in the predawn haze. I watch Nathaniel Hawthorne steer his boat to the bridge and he disembarks.

The author does not see me. He is taking watch of his footing as he digs his muddy boots up the steep bank. At the crest, he picks up the bonnet and shoes. I hear a deep sigh. Then with great effort he fumbles down the bank and places them into the boat. As the sun rises on the river, he climbs up the bank.

At last, Hawthorne steps onto the bridge, dragging his feet to the center of the platform only a few feet from me. With hands clasped together as if in prayer, eyes cast to the water, shoulders slumped, he leans over the rail. There is a terrible hunger in his face, something rawboned, mouth grim, legs stiff. He seems to be speaking, but his whispers are too weak to hear. I cannot see tears. I can hear stifled sobs.

“Nathaniel!” A woman calls from the lawn. Skirt lifted, she runs fiercely to the bridge and nearly throws herself into his arms.

“Sophia,” he pets her hair.

“Oh my dearest. How long have you been standing here on this bridge? Watching the river will not bring Martha back.”

“This night will strangle me yet. I can be no other place.”

“Hold me, Nathaniel. Tighter.”

She wraps her arms around his waist, then lifts her face to his. “Was it just you and Mr. Channing who found her?”

“General Butterick and his friend joined the search.”

“When Mr. Channing came to our door to call you to help, it was after midnight. Had he been searching for Martha long?”

“One of her students saw her bonnet and shoes on the bank at mid day. Her family had been searching the woods and the village most of the daylight. By midnight, there was nowhere else to look. But the river.” Hawthorne releases his wife and turns back to the water.

“Mr. Channing went to tell the family?”

“He has more courage than I.”

Sophia rubs his arm, leaving her hand on his chest.

“We sailed up and down the river for most of the night. Finally Butterick’s pole jagged on something at the bottom. We hooked her body out of the water with the hay rakes. Sophia,” he kisses her forehead, holding his lips against her skin a long moment, “I never saw, nor could I imagine such a perfect horror.”

She looks deeply into his eyes. “Oh my dearest, do take some comfort that Martha is out of her struggle.”

“I take no comfort in any of this. What utter despair she must have suffered to have plunged herself into these brackish waters.”

“Melancholia is a terrible curse.”

“Was she so filled with gloomy thoughts, that the multitude of them can steal her very life? Sophia, Sophia! When we lay her on the river bank, her body remained so stiff. Ghastly swollen and distorted,” Hawthorne raises up his arms, bends them like hooks, and claws his fingers open. “We could not get her arms down to rest at her sides. So clenched in her death throes—”

“Please, Nathaniel, do not speak of it. Let us remember her as a lovely young woman. What a pity, only nineteen years of age.”

“A remarkable woman. An intelligent woman. Channing reported that the girl excelled at the Academy, even winning honors. Was Martha so oppressed and confused here that she drove herself to destruction?”

“She was a poor farmer’s daughter with a bleak future. She had few friends, I’m told. There are perils in such isolation.”

“I am well aware of the perils of isolation, my dear.”

“For an unmarried woman, it is far more severe than for a man. I met Martha one afternoon for tea at Lidian Emerson’s. My impressions were that Martha Hunt was a bit of a misfit in Concord. Truly, Nathaniel, what intellectual opportunities could this young woman find here after her high achievements at the Academy? To milk cows and churn butter? To drill pupils in the alphabet? This community could provide her with nothing to match her ambitions.”

“I wish I had known her. Channing said she often walked alone in the woods. I never came upon her, not even once.”

“Did you know that Martha had refused a marriage proposal?”

“Did she? Why?”

“Her opinion was quite firm. She had no desire to be slave to household, husband, and family.”

“Slave? You mistake such a word, Sophia.”

“I do not mistake. Indeed, I have no agreement with Martha’s opinion. Domestic life is not slavery, but I will confess it has many limitations for women. Mrs. Emerson concurred that home and family create high demands and do isolate women from other callings. She did what she could to help Martha, even offering to lend her some of Mr. Emerson’s books. I daresay, she had taken to some of the thinking of Margaret Fuller about equal rights for women. Martha clearly preferred independence rather than the duty of marriage.”

“But what life would Martha have as a spinster and her limited means? Death was not an answer.”

“Providence has taken her, Nathaniel. Do not torment yourself so.”

“Sophia, I can’t help but ask, was there no clergyman to counsel her at such a time? No family member to hold her hand and offer sympathy?”

“Who can say?”

“Not even a stranger to pass by the river and offer a kind word before she took her last breath?”

“We shall never know what happened in her final hours. The past is in the past. What is it you call it, shadows? Martha is at peace, Nathaniel. Let it be so in your heart.”

“What peace is this? Her shadow will forever be on this river.”

“Oh my sweet, you are exhausted. Come back to the house. I’ve set a cornbread in the oven. And the huckleberries are ripe. We shall have them with sweet cream for breakfast. Come now.”

“Soon, I will come. Grant me a minute more.” He watches his wife move gracefully toward the apple orchard, then looks back in my direction.

Time shutters open like a camera; I feel it coil at the back of my head. Hawthorne’s face aligns directly with mine. I am afraid to look at him; his will penetrates my resolve. I examine his high forehead fringed with dark hair, the mile-long eyelashes, lips that curl. Our eyes meet in a fierce lock.

“Mr. Fane, good morning.”

I nod unable to find my voice.

“May I tell you, these glimmering shadows you see, they continually slide across the inward sky here. You hunt too deeply into this phenomena. I expect you know this.”

“Sir?”

“Your endeavor here, young man, is apt to create a new substance … where there remains mere shadow.” Hawthorne offers his palm. The rose, glossy with raindrops, hangs over his fingertips.

Somewhere between the darkness and the dawn, the bud bloomed into a stunning red.

“Such is your kindness. A fine deed that endures.” Hawthorne drops the flower to float downstream beyond the Old North Bridge. We watch it until it disappears into the glittering waves. He raises his eyes. “Onward, Mr. Edward Fane, onward.”

My eyes burn for a second and I blink. I reach for my meters. All diaIs are vibrating right off the charts. I am standing dead center on the bridge. My head is pulsing an illusive beat that is quite bearable. I almost like the rhythms. This trap door hasn’t fully closed.

Breathing a purer air, I walk off the bridge to the lawn. The rain has stopped. Clouds vanish. Sunlight breaks through the trees. Shadows stream everywhere—one grey shaft feels softly wedged into the left side of my skull.

From town, I hear church bells ringing faintly. I count twelve tolls for noon. Standing on the grass, before the path that leads to Monument Street, I have this deep desire to turn around. Does yesterday truly live in the past? Will Martha Hunt remain a lingering ghost streaming the ley line over the Concord River? Or remain a shadow embedded inside my head?

If tomorrows can emerge here, I will them to be present right this moment. I want to see Martha, standing on the bridge in her white dress with her hair blowing in the breeze. Will she wear the rose at the side of her head? Will she smile?

Dare I turn around?

Author's Note: In Concord Massachusetts, Miss Martha Hunt of Punkatasset Hill was found drowned in the Concord River, not far from the Old Manse, on July 9th 1845, by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ellery Channing, and others. Her death was termed "melancholy suicide." Mr. Hawthorne fictionalized Martha's death in his novel Blithedale Romance.

Opening lines are quoted from Hawthorne's The Haunted Mind.