|

WHISTLING SHADE |

by John-Ivan Palmer

More than any other Victorian author, Oscar Wilde has become a present day cultural franchise. He’d likely be surprised by all the gay bars that bear his name, even though some of their patrons may be less than intimate with his literary themes of cryptic identity. Given the attention he paid to his wardrobe of plumed hats, luxurious furs and lemon-colored gloves, he might regard the crass commerce in Oscar Wilde Tshirts and bikini undies as beneath his refinements. And one can only guess what he would think of the actor who assumed the name “Oscar Wilde” and starred in dozens of pornographic films like Puritan Video Magazine, Sins of the Flush and Humpmee Dumpmee, to name some of the more printable titles. Google the name and start reading eleven million hits.

All those hits might drop to a lower level of impossibility were it not for a decision he made in the lobby of the Albemarle Club in London on February 28, 1895. A hall porter handed him a small calling card. On it were written six words that would determine the playwright’s tragic fate. He should have torn it up and continued basking in fame and the arms of comely boys, but some deeper voice convinced him not to. On the card was printed the name “Marques of Queensberry.” The six words, barely legible and with one obvious misspelling, were: “For Oscar Wilde, posing as somdomite (sic).”

The Marques was a blowhard and bully known for his womanizing and gambling. He did not like the open way that Wilde, a married man with two children, was hanging all over his son, Lord Alfred Douglas, also known as “Bosie”, a spoiled snit who looks in photos like someone just let all the air let out of his head. One of his other sons, Drumlanrig, was also a Uranian, as the term was then for gay males, and died, possibly from suicide, after a sex scandal with a future prime minister. One thing for sure, the Queensberry boys had a taste for famous men. The Marques was convinced that homosexuals in general were conspiring to steal his sons’ manhood and indirectly his own. All his homophobic hatred became focused on Wilde.

The card was bait and Oscar went for it with the pluck of a mouse for a piece of cheese. It’s hard to comprehend how someone as ignorant as Queensberry could set such a lethal trap for someone as insightful as the author of The Importance of Being Earnest and The Picture of Dorian Gray, but the mechanisms of the trap had nothing to do with logic. Before the six words harpooned themselves so deeply into Wilde’s subconscious, a soirée palmist had given him an ominous warning, “Your most unusual destiny of success will be completely broken and ruined.” He was Oedipus the King ignoring Tiresias the soothsayer.

Leading up to the six words, Queensberry had been stalking Wilde and attempting to rush the stage at his plays and assassinate him with everything from vegetables to bullets. Wilde fled London with Bosie and went to Blida, Algeria, a popular cruising spot for European pederasts. They smoked copious amounts of hashish (for “peace and love”) and frolicked with Berber boys they picked up in the souk. André Gide, who was doing the same thing, happened to be staying at Oscar and Bosie’s hotel. Over dinner Wilde told Gide how he was going to sue Queensberry for libel and Gide’s response was—don’t do it, Oscar.

Wilde replied cryptically that not to do it “would be going backwards.” At this point it was clear to everyone except him that he was controlled by something very dark.

When they returned to London, Wilde’s long-suffering wife, Constance, went to the Savoy Hotel, where Oscar and Bosie were holed up in connecting rooms, and begged him to give up all this Uranian adventurism and come home. Richard Ellmann reports in his biography of Wilde that one of his sons warned, “naughty papas who made mommie cry were in for big trouble.” When Oscar told his friend, Frank Harris, author of the wicked memoir My Life and Loves, that he was going to put everything he had into squashing the 9th Marques of Queensberry in court, Harris echoed everyone else. Don’t do it. Stop before it’s too late. But Wilde would not stop. Robbie Ross, who at age fifteen first introduced the married playwright to Uranian love, suggested that he ask his lawyer, C. O. Humphreys, what would happen, hypothetically speaking of course, if Queensberry’s six words might, uh, like be true? Wasn’t it a little like a mouse libeling a cat for calling it fuzzy? Wilde’s swishy carryings on about London were so well known they were parodied in cartoons and satirized on stage. Humphreys himself took the liberty of asking him directly if he could swear as a gentleman he was not a sodomite. With a straight face he said no. At that point Oscar’s nose must have grown as long as his shirt sleeve.

In André and Oscar, The Literary Friendship of André Gide and Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Fryer writes, “the evidence seems overwhelming that Oscar’s physical relations with his ‘golden boy’ [Bosie]...remained on a schoolboy level...which means nonpenetrative sex...Douglas was an active sodomite...with rent boys...Oscar was not...[which] helps explain why Wilde was so angered by Queensberry’s allegation of ‘posing sodomite.’” Fryer does not mention what that overwhelming evidence might be, since it’s hard to prove a negative, but short of a photograph capturing the act and the face together it seems that no evidence could be “overwhelming.” It was not sophistry over sexual technicalities, but some ghastly thanatological urge that drove Wilde over the edge of his own flat earth.

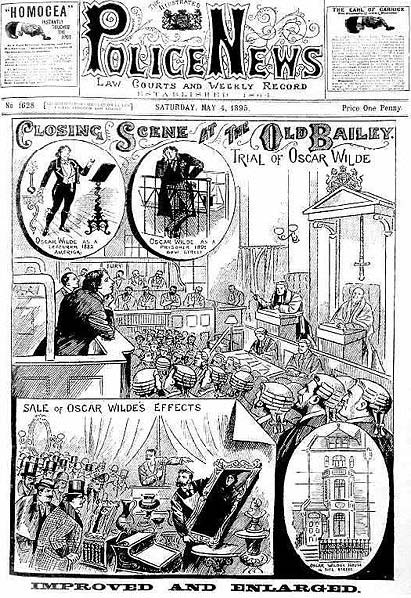

Against nearly everyone’s advice he went ahead with his libel suit. In court he was the consummate entertainer, playing to a packed courtroom and getting rollicking laughs and applause with his inimitable wit. Any performer knows the high that comes from a good performance and the ease with which one can slip into riskier material. Under questioning from Queensberry’s attorney, Wilde hubristically asserted, emphasizing his words with those gestures he was so noted for, that he would “with pleasure” pick up an Arab boy and take him to his rooms “if he interested me.” One can just see his friends looking down, pinching the bridge of their noses and saying to themselves, Oscar, please, for your own sake, for the sake of your children, stop.

Following Wilde's wild admissions, the Queensberry legal team trotted out a hooker parade of rent boys who were bribed, threatened and coerced into accusing the playwright of "gross indecency," a euphemism for doing what gay men have always done. Wilde’s case crumbled before his eyes and the Marques won.

Here was the payoff for Queensberry. Now that he was innocent of libel as he wagered he would be, that meant, legally speaking, his six words had to be true. And if they were true, the authorities had no choice in light of the publicity over the trial but to indict Wilde for sodomy under Section 11 of the Labouchere Amendment. There was nothing ebullient about the drama that followed. Wilde’s intentions of homosexual liberation only resulted in a gaybashing frenzy that swept London until there was, as Frank Harris put it, a “strange exodus” of Uranian men by the “wind of terror.”

Even at this dire point Wilde’s friends repeatedly pointed out to him that all was not lost. There was a window of time between Queensberry’s acquittal and Wilde’s trial for sodomy when he could have joined the stampeding exodus. But he did not. Even Bosie’s brother, Percy, who posted Wilde’s bail which he could not afford to lose, said get away while you can. Two of his closest gay friends, Robbie Ross and Reggie Turner, told Wilde how easy it would be to take a train to Dover, then ferry across the channel to France. He was already fluent in French and his play Salomé, which he wrote in French, was a great success in Paris. A few years earlier Lord Arthur Somerset had found himself caught up in a similar gay sex scandal and all it took for him to avoid jail was a simple side shuffle to France, where things worked out quite well. Bosie had already joined the herd of absconders and was waiting for Oscar in a Parisian hotel. Frank Harris even went so far as to arrange for a private yacht to sail him to freedom. It was docked and waiting with a stash of money. All he had to do was climb aboard. He could spend the rest of his life smoking hash in Algeria and rolling around with naked twinks. But for reasons known only to the playwright, he stayed in London where doom awaited him.

The rest of the story is well known. Wilde was found guilty and sent to Pentonville Prison where conditions were worse than in many third world prisons today. Starvation, forced insomnia from beds made only of planks and chronic diarrhea with forbidden toilet visits reduced Wilde to such a state that even hardened guards became violently ill when they entered his cell. He was transferred to Wandsworth Prison, past jeering, spitting mobs. He contracted dysentery (for which he was refused treatment) and fell from exhaustion, rupturing his eardrum. The complications would later kill him. Conditions marginally improved at his final transfer to Reading Prison where he was at least allowed writing materials. It was there that he composed De Profundis, his lament to Bosie of the dove-gray eyes and the temperament of a snake. Upon release in 1897 the injured jailbird was bullied and ridiculed on the street and when he sat in restaurants people got up and left.

One can’t take away from Oscar Wilde his distinction as martyr for the gay cause. He openly defended Uranian love at a time when it was obviously not safe to do so and lost everything. So what drove him to crucify himself when so many avenues of escape were available?

It might not be inapt to compare Oscar Wilde to another homosexual self-saboteur, Yukio Mishima, the Japanese author of a hundred books who was expected to win the Nobel Prize. At the height of his fame in 1970 he talked a sex pal into using a samurai sword to cut off his head. Both Wilde and Mishima were married, both had two kids and both were endowed with naturally weak physiques and were treated like girls by their mothers. Each found a strange homoerotic kick from crucifixion pictures and the image of St. Sebastian’s young and beautiful body pierced with arrows. Mishima was a fan of Wilde.

Barbara Belford noted in her study of the playwright that in the late 19th century “decadents and Uranians rushed into the Church of Rome” because the fleshly iconography both excited desire and condemned it, understandable in those born to love in a way “that dare not speak its name,” as Bosie (not Wilde) famously put it. Wilde flirted with Catholicism throughout his life and became a deathbed convert, baptized by his former underage lover, Robbie Ross (later his literary executor). By the time Wilde died of what was then called encephalitic meningitis as a result of his ear injury in prison, the noxious Bosie, whom Wilde said he “loved with Christ’s heart,” had become his Judas many times over, squandering what little money Wilde had and killing him with hateful words.

In the poem “Hélas!” Wilde writes that his destiny was

“...to drift with every passion till my soul / Is a stringed lute

on which all winds can play...” Few of us need more time with

that one. The enigma emerges in the next two lines: “Is it for

this that I have given away / Mine ancient wisdom, and austere

control?” In spite of warnings from so many people who said

don't do it, Wilde went ahead and did it anyway, answering his

own question in a dramatic finale, where his personal tensions

between desire and condemnation were finally resolved by

death.