|

WHISTLING SHADE |

by Thomas R. Smith

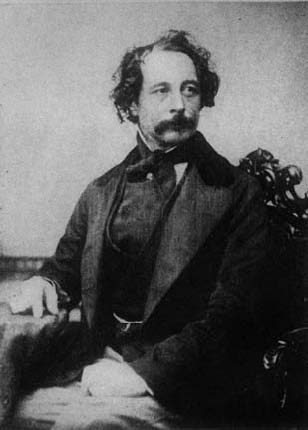

Two years ago, I embarked on the modest, extremely occasional project of filling some gaps in my literary knowledge of Charles Dickens. I did so partly under the influence of Jane Smiley’s excellent brief study of Dickens in the Penguin Lives series and partly from a conviction, rooted in my early upbringing, that the classics are a birthright and crucial component of a fulfilled human life.

I never expected to read Dickens. Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities (or at least abridged versions of them) had figured into my high school education but finally hadn’t made much of an impression on me. In fact I’ve carried through most of my adult life an unexamined, over-simplified image of who Dickens was, that is, a shameless sentimentalist, perpetrator of such culturally persistent lines as “Please, sir, can I have some more?” (Oliver Twist) and “God bless us, everyone” (A Christmas Carol).

That began to change when one Christmas, in a mood of holiday sentimentality myself, I spent a couple of evenings pleasurably rediscovering the latter story and encountered, along with the predictably heart-tugging Tiny Tim, a 19th century London chillingly harsh in a way I hadn’t remembered from my formative brushes with it.

From there it was a short distance to Jane Smiley. I’ve so far absorbed the approximately 2,000 combined pages of David Copperfield, Great Expectations, and, mostly recently, Dombey and Son (recommended by Smiley along with A Tale of Two Cities and Our Mutual Friend, and in the above order, as a remedial course in Dickens).

Now, more than halfway into my sporadic project, I can’t help noticing that Dickens is everywhere I look. Yes, last year was the 200th anniversary of Charles Dickens’s birth, but that can’t by itself account for the author’s evident ubiquity on our current cultural landscape. Movies, BBC dramatizations, magazine articles—Dickens is all over the place these days. This year even my small town’s public library has made Dickens a focus of their fall programming. What exactly in our present situation lends itself to this fresh round of Dickens appreciation? What collision of time and circumstance has occurred to make Dickens, as he indeed appears to have become, a relevant literary voice for the 21st century?

I find one clue in Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Romantic and Postromantic Poetry, edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey C. Robinson. Establishing a link between the mainly 19th century poets assembled in that volume and poets of the 21st century, the editors remark of the current historical moment:

The nineteenth century begins again: nationalism, colonialism, and imperialism, ethnic and religious violence, growing extremes of wealth and poverty, all reemerge today and with a virulence that calls up their earlier nineteenth century versions and all the physical and mental struggles against them, struggles in which poetry and poets took a sometimes central part....

The editors take a global view not contradicted by the growing turmoil and governmental dysfunction in the US Congress as well as in individual states. Everywhere in the nation, including my home state of Wisconsin, a fanatical minority bent on reversing hard-won progressive policies of the past hundred years, to quote Washington Post columnist Harold Meyerson, are “repealing the twentieth century.” Rights of women and workers, access to health care, education and a clean, livable environment are all under concerted assault. Taking advantage of our current national episode of economic uncertainty, moneyed interests attack in the name of “freedom” legislative restraints that have stood in the way of their complete control of the wealth of the nation.

In short, current efforts to annul the democratic experiment threaten to return society to conditions resembling those Dickens denounced in his novels. As Rothenberg and Robinson observe, almost every brutal and cruel social abuse of the past has been resurrected and proposed by lawmakers either ignorant or contemptuous of history. How far back have we in fact slid? Recently Attorney General Eric Holder publicly asserted that NSA leaker Edward Snowden would not be tortured if he returned to the US. The plain fact that such an assurance is less shocking to us now than it would have been twenty or thirty years ago speaks to our descent into abuses for which enlightened American democracy was supposed to be an antidote. The right-wing roll-back on union and women’s reproductive rights appear almost perversely calculated to bring back the bad old days of exploitation, labor violence and deadly backalley abortions. Some in the GOP are now pressing for repeal of the child labor laws. Dickens would have understood the human and social costs of such damaging legislative regression.

Were Dickens alive today the multi-billionaire business libertarian Koch brothers, David and Charles, who have funded so much of the regressive right-wing social and economic agenda of the Tea Party, might make convincing villains in one of his novels.

If the Koch brothers represent the present triumph of predatory capitalism over more humane guiding principles of society, then the senior Paul Dombey in Dombey and Son is Dickens’s near-definitive cautionary example of the same arrogant greed in the England of the mid-19th century (the original serialized Dombey and Son ran from 1846 to 1848).

Dombey is one of Dickens’s more unpleasant creations, not for any outright malevolent villainy, but because of his repellent coldness. Dombey’s sin is his dedication not to ostensibly evil or criminal deeds but rather to a “business as usual” ethos taken to pathological extremes. Jane Smiley identifies the theme of Dombey as “the commodification of familial relations.” Dombey views his son, who carries both the senior Dombey’s name and worldly expectations, almost strictly in terms of a future business partner. Thus the son is seen by Dombey chiefly as an asset.

Dombey’s other child, Florence, a girl and therefore by definition not a successor to the Dombey family business concern, seems less than nothing to him. Dombey’s disdain for Florence turns outright hateful following the son’s death a quarter of the way through the novel. Much of Dombey’s long mid-stretch unsparingly anatomizes the father’s progressive distancing from the daughter. The senior Dombey in fact emotionally starves the loving and devoted Florence. Effectively locked out of her father’s affections, Florence inhabits a “wilderness of a home”:

Florence lived alone in the great dreary house, and day succeeded day, and still she lived alone; and the blank walls looked down upon her with a vacant stare, as if they had a Gorgon-like mind to stare her youth and beauty into stone.

Florence lives “alone” in the great house because Dombey isolates himself, unapproachable and unassailable in his room, object of a fearful and unearned reverence. This barricaded father embodies, as though a primal force, heartless egotism unchecked by a sense of obligation to anyone except himself. Dombey finally is the only one who matters to Dombey, all others existing to buttress and glorify his grossly inflated sense of self-importance (even Dombey the younger matters only to the degree that he embodies an extension in time of the Dombey name under the aegis of the corporate entity “Dombey and Son”).

Lest Dombey surrender to soulsearching and perhaps actually question his monumental self-centeredness, sycophants are kept near to reinforce his assumption of supreme significance. The most noxiously self-aggrandizing of these, a flatulent blowhard named Major Bagstock, at one crucial moment rushes into the breach with this toxic advice: “...don’t be thoughtful. It’s a bad habit. [...] You are too great a man, Dombey, to be thoughtful. In your position, Sir, you’re far above that kind of thing.”

Such refusals of moral reflection have enabled western capitalism from its inception. We imagine all too easily such advice being given to our contemporary Dombeys, the Waltons and Kochs—“Don’t be thoughtful. You’re far above that kind of thing.” So say the shareholders and the legislative strategists of the American Legislative Exchange Council to our elected officials. (For that matter, so say the commercial TV networks to their viewers.)

Dombey inevitably gets his comeuppance. Betrayed by a trusted associate and financially ruined, Dombey comes around at last, as we knew he would. He softens toward Florence and her forgiving husband Walter, his employee (whom Dombey has separated by exiling the latter to one of the company’s far-flung posts), and becomes a kindly grandfather to her children.

A happy ending, all well and good, and certainly what Dickens’s public would have demanded after the dispiriting trek over Dombey’s emotional glacier. A happy ending that yet only slightly sweetens the author’s increasing skepticism over society’s reformability. In fact Dickens came to believe that only individuals, and not society itself, could be reformed: The system itself would remain hopelessly rotten and corrupt.

And maybe philosophically that’s where many of us now find ourselves. If the world of Dickens still doesn’t look quite like our own, we may yet recognize familiar tensions pulling us collectively, once more, toward the increasingly unregulated power of moneyed entities. Our cultural recognition of the relevance of Dickens may not be and probably isn’t entirely conscious in its nature.

Seldom has a major character in a novel of Dombey’s magnitude received so little backstory. As Jane Smiley points out, the character of Dombey is strikingly unpsychological: “...the origins of his pride and remoteness are not at all investigated.” Dombey, it may be, symbolizes a persistent force manifesting in human affairs, a potential inherent in our nature. Faith in progress would have us believe that we in the West are done with all that; enlightened 20th century legislation has ended the main abuses of the industrial era. However the figure of Dombey viewed as a persistent historical tendency uncomfortably suggests otherwise.

Since the Tea Party’s “Red Tide” election of 2010, we’ve seen what we might call the Dombey side of American politics working overtime to roll back policy and legislation that protected ordinary citizens from the greed of the plutocracy. Dickens implicitly warned us that this would happen. He has no political solutions for our present dilemma, but he can help us recognize more clearly the forces arrayed against our happiness, health and rights, just as he did with the “99 per cent” of his day.

The Kochs of this world may never

undergo Paul Dombey’s dramatic change

of heart, and only a fool would wait for

them to do so. Meanwhile we have Dickens

to help us identify and name where

we’ve been and seem to be headed again.

How to proceed effectively and creatively

from that recognition is another

matter, in which artists, writers and

poets must engage if we wish to be

remembered with the gratitude we still

feel, or feel again toward Charles Dickens,

that defining voice of the first 19th

century