Encountering Walt Whitman's Illegitimate Great-Grandson

On January 16 1968, I entered the famous Shakespeare & Co. bookstore at 37 rue de la Bucherie in Paris for the express purpose of introducing myself to the owner, George Whitman, self-proclaimed illegitimate great-grandson of Walt Whitman. I’d read about him in Paris Magazine, the literary journal he edited. I was almost twenty-one and came from a family of entrepreneurs who believed that success was a matter of knowing the right people. You approach them with confidence and say, “Here is what I have. You need it.” I was certain that the editor of a magazine that published the likes of Sartre, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg and Marguerite Duras would be impressed with Coins Rolling in a Dark Room, my collection of unpublished poems.

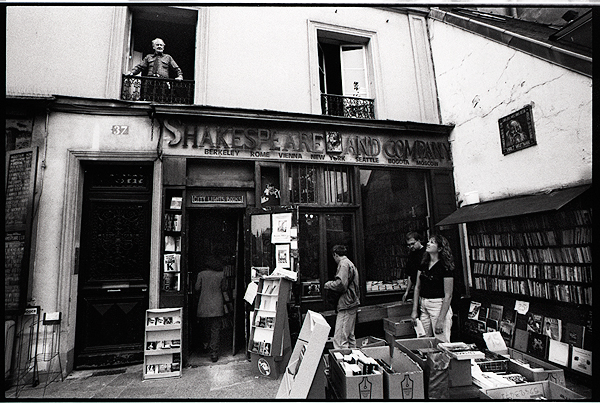

Whitman’s bookstore opened in 1951 as Le Mistral, and took its name from the previous Shakespeare & Co. established in 1919 at another location by Sylvia Beach, the original publisher of Ulysses. Her shop was the gathering place for famous authors like Hemingway, Joyce, Gide, Veléry, Beckett and others of similar stature. When she closed the store she bequeathed its legendary name to Whitman.

I walked through the door and encountered a scene that reminded me of busy elves in Santa’s workshop. It was “salon night” for insiders only when aspiring authors hopeful of fame cleaned windows, dusted counters, arranged books and washed the floor in exchange for free lodging on one of several beds available throughout the building. The man recognized by the New York Times as “a cultural beacon” was not one to sit back and let his elves do all the work, so he too was down on all fours with a bucket. As I noted in my journal he resembled Ho Chi Minh, with parched skin stretched over a skeletal face like papier-mâché. The only tooth I noticed was one barely surviving incisor protruding from his lower gum line. He had a grey Mephistophelian goatee.

I stood above him like I was the patron and he was the colonial minion. Sparing no effort to make an impression, I dressed for the occasion in a white shirt of Egyptian cotton (hand-me-down from my father), a silk tie (the same) and a Bogart trench coat. I waited for the outstretched hand and immediate interest in who I was and especially in what I clutched under my arm. In preparation for my entrance into Paris I had studied French for two years and rehearsed in my mind a repertoire of bon mots for every situation I could anticipate but, as it turned out, I had failed to anticipate them all.

“Got something? Just set it down,” he said quickly as if it were one polysyllabic word. “I hope it’s an article.” He went back to scrubbing the floor. No handshake.

House policy as outlined in one of his Paris Magazine editorials was that one should come into Shakespeare & Co. and make oneself at home. So I set my poems on his desk and began looking around. I asked a couple of stock arrangers where I might find English translations of Auguste Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, but they were no more welcoming than Whitman. After all, I could be competition for their free bed. On the second floor I met a man about my age in a sweater that looked like it had been clawed apart by a cat. He was standing beside a desk on a slightly elevated platform and wielded a feather duster. On the desktop sat a typewriter and a stack of manuscript pages like a museum tableau. Each of us were too self-conscious to inquire about the other, so I never knew if he was a poet, a novelist or someone who would later become successful like the journalist James Campbell, one of Whitman’s overnighters. He told me the desk was the honored workspace of the current writer in residence, whose name he expected me to recognize but I did not. I thought if I played my cards right perhaps that desk could be mine.

I returned to the main floor where Whitman had finally gotten around to sitting at his own desk to read my poems. Once more I stood over him, this time like a cuisinier awaiting for praise of a delicately prepared chef-d’oeuvre. He began with “Psycho Rapture” (“all is calm / I’m a ship of fire / plunging over the edge / of my flat earth”), and set the page aside face down with a look of annoyance. “Compulsive Travel” (“wasting secrets like money / in a sandstorm of laughter”) got a mere glance-over and “Massage Parlor Honeymoon” (“move over drummers / atomic workers and guys who live in grease”) was dispatched with a long and disgusted sigh. He hardly began “Face Focus Burnhole” when he added it to the others and pushed it all away like a plate of awful food.

“Interesting little scraps of writing,” was all he could come up with by way of a compliment. “Why don’t you write something about Samuel Beckett?” With that he left the room.

I backed away and sank down on a bench where people had put their coats and purses. I leaned against a backdrop of burlap fabric that covered the wall and tried to look, if not feel, significant by removing a pack of Gauloises cigarettes. I did not smoke, or at least not very much, but aspired to imitate the way Jean-Paul Belmondo talked with a cigarette bobbing from his lips in Breathless. To scrubbers and wipers I stood out not only as overdressed for the occasion but the only one in the store not working. For all they knew I could already have been famous, perhaps the illegitimate great-grandson of Villiers de L’Isle-Adam. I removed a small box of wooden matches and lit one. It broke in half, propelling the ignited head over my shoulder where it immediately set the fuzzy burlap on fire. I desperately pounded out the creeping flames then sat back down, the unlit Gauloises still in my mouth.

It happened so fast I don’t think anyone noticed except perhaps one cleaner who eyed me askance. When I took out the matchbox to give it another try I noticed between my feet a billow of smoke rising up from under the bench, which I pulled away from the wall, knocking the purses to the floor and spilling their contents. The lit match head had evidently dropped to the base of the burlap and ignited it from the bottom. As anyone knows who has fought an out-of-control fire, the body is seized with the same panic as if attacked by a wild beast. The situation was now very much noticed and literati dropped their rags and brushes and rushed over to join me in fighting aggressive flames rising to engulf the wall. A would-be Irène Némirovsky threw a cup of tea at the conflagration and a putative Ezra Pound, who had at least created a nice facsimilé beard, smothered out the rest with a woman’s coat. Whitman arrived on the scene with grave concern.

“What happened?” he asked

“Someone tipped over an ashtray,” said Young Ez.

I had nothing to add as Whitman and the others stood looking at me and judging me. Now the only thing burning was my face and ears.

I finally lit the Gauloises and let it hang from my lips. It did not bob up and down. Not wanting to look like I was running away, I edged casually toward the door and picked up what looked like a discarded copy of the Herald Tribune. With my head down pretending to read it, I made my way out, hopefully unnoticed. But then I heard Whitman’s voice behind me.

“You mean you’re going to sneak out of here with a paper?”

Besides being a dilettante and an arsonist I was now a shoplifter. Confusedly, I gave him back the paper and left. I heard him say behind me as I headed down the Rue de la Bucherie that I should “stop acting like a tourist.”

Had I stubbed my ego, removed my trench coat and tie and gotten down and scrubbed his floor, I might have insinuated my way into one of Shakespeare & Co.’s free beds, maybe worked my way up to that hallowed desk on the second floor, had the honor of prying Ginsberg’s lecherous fingers off my twenty-year-old body or even sleeping with the ageing Marguerite Duras. But instead I came dangerously close to burning to the ground one of the great landmarks of twentieth century literature along with all its priceless artifacts and maybe a poet or two who couldn’t get to the door fast enough. My name would have been associated with Herostratus, who immolated the Temple of Artemis, or Hayoshi Yoken who burned down the Temple of the Golden Pavilion. I would have had to spend the rest of my life arguing it was an accident, that it had nothing to do with being snubbed by the illegitimate great-grandson of Walt Whitman (which, it turns out, he wasn’t, according to his obit in the New York Times) who dismissed my poems as “little scraps of writing.” Against such a tragedy his phony pedigree, like my trench coat and Gauloises, would pale as forgotten affectations.

Over one of the doorways was a quote Whitman falsely attributed to Yeats: “Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise.” A nice sentiment that did not apply that night to a Gaulouises-smoking donkey in a trench coat. I still consider it an honor to have made the acquaintance of someone who arranged for William Burroughs to read from Naked Lunch before it was published, was on a first name basis with Lawrence Durrell and no doubt exempted his friend James Baldwin from scrubbing the floor. Opening his doors over the years to a claimed 40,000 aspiring writers had to have had its drawbacks. Even allowing for decimal drift and the number was actually 4,000, or an even more realistic 400, he still must have been no stranger to ingratitude and undoubtedly his property had a habit of walking away. He had a right to be repulsed by me.

Shortly before I graced Shakespeare & Co. with my presence it had been shut down for a year because of “licensing violations,” possibly related to the Parisian fire code. Everyone smoked everywhere and the place was a firetrap. One time a fire did get out of control on the second floor destroying 5,000 books. That might have been why he read “Face Focus Burnhole” as more than just a ludicrous piece of apotropaic juvenilia. Neither of us could have foreseen his own misadventure with fire forty years later when he would attempt to trim his hair with a lit candle for a TV documentary and set his whole head aflame. Fortunately it was a minor incident.

Several poems that he never looked at in my hopeless collection were later published. The other “little scraps of writing” I eventually tossed to the winds where they dispersed like the cloud of alternative possibility that hangs over our smallest actions.