The Endearing Colette

One hundred years ago, in the early months of World War I, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette was riding in a blacked-out train car with false papers, en route to the citadel of Verdun on the Western Front. It was a thirty-hour journey, and when she arrived in the town she had to keep herself hidden indoors, staying away from the windows and only going out clandestinely at night, like the heroine of a spy novel. It was a strange role for a writer known mainly for her expertise in love, the stage, and matters of the boudoir. But being Colette, the explanation of the intrigue was simple—a man was involved.

Her second husband, Henry de Jouvenel, was a lieutenant in the 29th Territorial Infantry, stationed at Verdun. As civilians were not allowed at the front, Colette and the other officers’ wives in Verdun lived a secret life behind closed doors. She was a willing prisoner, cooking and cleaning for Jouvenel and composing what would become the libretto for Ravel’s opera L'enfant et les Sortilèges. As she wrote in a letter to her friend Annie de Pène:

I am all in favor of life. (Why are you laughing?) I simply mean that I am passionately in favor of life. Horror of horrors, I have to live behind shutters. But I am very well. I am enjoying the calm that comes to people who have achieved their aim in life. The guns mark the seconds with a good reassuring beat. Below me, there is a very pretty garden with birds in the chestnuts and the lilacs.

Colette was forty-two at the time; she had already written the famously scandalous Claudine novels, divorced her first husband, earned her own living as a music hall actress and caused a riot by kissing her lesbian lover Mathilde de Morny on stage at the Mulon Rouge. She’d also had a daughter with Jouvenel, Bel-Gazou (currently a toddler being cared for by a nurse in southwest France), flown in an airplane, worked as a reporter, and written The Vagabond, a ground-breaking feminist novel. She had, in short, already lived a full lifetime’s worth of memories. But Colette would survive the First World War, as well as the Second, writing her most highly esteemed novel (Chéri) as well as her best-known work in English, Gigi. Her marriage to Jouvenel was not to last, but she was to remain “all in favor of life” until the end, endearing and enduring, by turns harsh and sympathetic, but always writing from the heart.

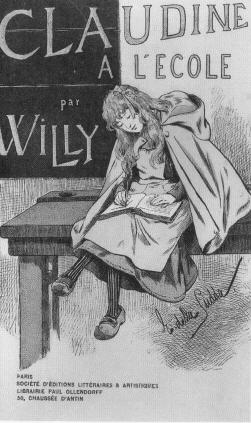

Claudine in School

Colette was of a generation that Yeats referred to as “the last romantics.” She grew up steeped in Balzac, and though her fiction is closer to Zola with its naturalistic detail and open-ended narrative style, all of her major works revolve around one chief conflict: the clash of inner emotion with outer reality. And most often, with Colette, the inner emotion is love—or, at least, lust.

Like Edna St. Vincent Millay in America, Colette was a village girl who lit up the big city with her prodigious talent and Byronic personality. In the case of Colette the village in question was Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye, in Burgundy, where she was born in 1873. Her father, a retired captain with a wooden leg who dabbled in science and the arts, and her mother, an unconventional but refined woman of mixed African and Creole ancestry, ensured that the semi-genteel Colette family were outsiders. We can vividly imagine life there in the 1880s, thanks to Colette’s first novel, Claudine in School (Claudine à l'école), which is a lightly dressed up reminiscence of her own school days.

Claudine is a pretty and precocious spitfire of fifteen in her last year of school, watched over, rather haphazardly, by her eccentric father, a naturalist with a mania for snails whose time is mostly taken up writing a monumental tome entitled Malacology of the Region of Fresnoi. At school Claudine is by far the brightest pupil—and also the most disobedient. She has a crush on the new assistant mistress, Aimée, which is returned and goes as far as kissing and cuddling before the Headmistress, Mademoiselle Sergent, ugly and cunning and probably lesbian, becomes jealous of Claudine and ends the relationship. Much of the action takes place in the classroom, where Claudine’s high-spirited irreverence is on display. After Aimée breaks off their relationship, Claudine makes her former confidante a target of disobedience:

“Claudine, to the blackboard. Extract the square root of two million, seventy-three thousand, six hundred and twenty.”

I professed an intolerable loathing for those little things you have to extract. And, as Mademoiselle Sergent wasn’t there, I suddenly decided to play a trick on my ex-friend; she had only herself to blame, the fickle wretch! I hoisted the standard of rebellion. Standing in front of the blackboard, I shook my head and said gently: “No.”

“What do you mean, no?”

“No I don’t want to extract roots today. It doesn’t appeal to me.”

“Claudine, have you gone mad?”

“I don’t know, Mademoiselle. But I feel that I shall fall ill if I extract this root or any other like it.”

“Do you want a punishment, Claudine?”

“I want anything in the world, except roots. I’m awfully sorry, I assure you.”

The class jumped for joy; Mademoiselle Aimée lost patience and raged.

Claudine in School is written in the tradition of a bildungsroman, and is similar to other coming-of-age novels such as Tom Brown’s School Days, The Catcher in the Rye, and the Harry Potter series. But while a bildungsroman typically depicts the main character attaining maturity through experience of the “real” world, Claudine in School does the reverse. Claudine’s teachers succumb to childish jealousies and petty spats; one of the masters falls in love with Claudine, while the District Superintendent attempts to feel her up in the school hallway. The adults around her, with all their pretense of seriousness and wisdom, are just as immature as Claudine—and she’s smart enough to know it and exploit their weaknesses for her own amusement. As one of the masters declares, “I believe that girl knows more about things she oughtn’t to know than she does about geography!”

In her real-life childhood, Sidonie-Gabrielle was much like Claudine. She was a bit of a hoyden, romping through the woods and fields and insisting on being called “Colette” at school, as the boys addressed each other by their last names. When her father took an interest in becoming a député she accompanied him in his politicking, getting tipsy from drinking mulled wine with the voters, until her mother put a stop to it. Colette soon grew out of her tomboyishness, but her love of the country was to remain, and become a strong element in her fiction. Claudine in School leaves the classroom for scenes of bucolic rapture when our heroine visits her friend Claire, who is out of school now and looking after twenty-five sheep (“a slightly comic-opera, slightly absurd little shepherdess...”) but mostly occupied with her rocky romances among the country swains:

While she was telling me the meagre news of the past four days, along with her misfortunes, it was I who kept an eye on the sheep and urged the bitch after them: “Fetch them, Lisette! Fetch them over there!” and I who uttered the warning “Prr ... my beauty!” to stop them from touching the oats: I’m used to it.

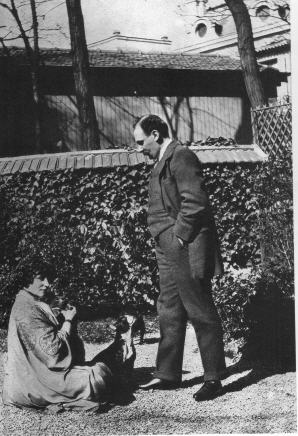

Yet in the end, it was the fashionable allure of Paris that Colette found stronger. Her ticket out of Saint-Sauveur came in the person of her first husband, the writer and critic Henry Gauthier-Villars, known to most as “Willy”. A friend of the family (his father had served with Captain Colette in the army), Colette first fell in love with him in 1891, when she was nineteen. Willy was thirteen years her senior, and already a well established man of belles-lettres in Paris, famous for his quips and his rakish lifestyle. To Colette, Willy was cultured and urbane, and, most importantly, he made her laugh. Though Willy was by no means handsome, with his beak of a nose and paunch of a stomach, Colette was swept off her feet. Willy seemed equally enthralled—with her long golden hair and deep-set almond eyes, Colette was a striking beauty. When a gossip newspaper printed an item warning “an exquisite blonde whose marvellous hair has made her famous” to “follow Mephistopheles’ advice and not to give away any kisses until she has a ring on her finger,” Willy fought a duel with the editor and wounded him. Shortly after that, in 1893, the couple were married and thereafter lived in Paris.

Together, Willy and Colette made a brilliant society couple; Paul Valéry, Claude Debussy, Toulouse-Lautrec, and José Maria de Hérédia were among their acquaintance, and Colette met a young and unknown Marcel Proust at a salon hosted by Anatole France’s mistress, Madame Arman de Caillavet. Fin de siècle Paris was enchanted with Colette’s guileless, country manners and her spontaneity (as when, for instance, she made sorbets out of jam and snow from the windowsill). She and Willy were a “modern couple”, allowing each other liberty to pursue their own relationships. For the rather dissolute Willy this included a string of mistresses (actresses, studio models, waitresses). Colette was jealous, but she had admirers of her own—and as she was bisexual, her flirtations were with both men and women. At one point Colette and Willy learned that they were both lovers of the same woman, Georgie Raoul-Duval.

Though a glamorous couple, Willy and Colette were not wealthy. Willy made most of his money writing; he’d had a collection of sonnets published, and wrote reviews for various newspapers. He also published novels, but these, though they bore the name Willy, were written by ghost writers, and only lightly edited by the “author.” Some of Willy’s “ghosts,” like Marcel Schwob, were acclaimed authors in their own right who needed some extra cash. Willy, too, ran short of funds from time to time, and in 1894 he had the idea of asking his wife to write something of her jolly school days in Saint-Sauveur. Colette, who thought of herself much more of an actress or dancer than an author, was nonetheless flattered, and took the project in hand. Willy originally dismissed her rough draft as the memoirs of a girl; but two years later, discovering them in a drawer, he started rereading them and realized what a blunder he had made. Claudine in School, lightly edited by Willy, was published in 1900 and sold forty thousand copies in four weeks.

The book’s success was mostly due to the man whose name was on the front cover. Willy got the book into stores, inserted rumors about it in newspapers, made posters and postcards, and even had a line of Claudine merchandise created (collars, hats, perfume, cigarettes and—of course—dolls). With the extra money, Colette was given a monthly allowance from her husband to buy dresses. But she also had to work, creating Claudine sequels. After taking her dogs (and sometimes her cat) for a walk in the Bois de Boulogne, Colette would be locked into her study by Willy for four hours to produce the next installment of Claudine. The result was that three additional novels were released in quick succession. Claudine in Paris (Claudine à Paris) appeared in 1901; it has Claudine’s father bringing her to Paris to publish his monumental Malacology of the Region of Fresnoi. She meets her dandified cousin, Marcel, but is more taken with Marcel’s divorced father, Renaud—a stand-in for Willy. Claudine Married (Claudine en ménage) is a thinly veiled fictionalization of the affair with Georgie Raoul-Duval—it sold seventy thousand copies in three months when it was published in 1902, the year Colette cut her famous golden locks and started the women’s fashion for short hair that was to take hold in the next decade and into the ‘20s. The fourth novel in the series, Claudine and Annie (Claudine s’en va) shifts the first person narrator from Claudine to the innocent and sheltered Annie, who is both taken aback and tempted by Claudine and Renaud’s unconventional lifestyle.

Though more sophisticated in tone, these later chapters in the Claudine saga lack the freshness and unpredictability of Claudine at School. Still, they have Colette’s charming style of writing—filled with dialogue, some quickly sketched characters and settings, plenty of emotion and almost no background (a technique Hemingway would later employ in a much more stylized way). What makes Colette’s informal, almost improvised narration piquant is her attention to naturalistic detail. Take, for instance, Claudine’s attack of homesickness in Claudine in Paris:

Once again I saw the transparent, leafless woods, the roads edged with shrivelled blue sloes and frost-bitten hips, and the village built in tiers, and the tower with the dark ivy—the only thing that remained green—and the white School in the mild, unglittering sunshine. I smelt the musky, rotten smell of the dead leaves; I smelt, too, the vitiated atmosphere of ink and paper and wet sabots in the classroom. And Papa, frantically clutching his Louis XIV nose and Mélie, anxiously fiddling with her breasts, thought I was going to be seriously ill again.

By the time Claudine and Annie appeared, it was more or less an open secret that Colette was Claudine’s creator. The first book to have her name on the cover (as “Colette Willy”) was Dialogues de Bêtes (often translated as Barks and Purrs), a slight, droll collection of dialogues between Kiki, a Maltese cat, and Toby, A French Bulldog. Colette was fond of animals, and in almost every work one can find a minor role for a cat or dog, a Fanchette and Fossette. In the case of Kiki and Toby, they were real pets who were her companions at Les Monts-Boucons, the estate Willy had bought in the south of France so that Colette could work in peace. Though she still reveled in the decadent celebrations among her and Willy’s bohemian friends (on one occasion she jumped naked out of the large cake served for desert) her patience with Willy’s endless affairs and bullying was running thin. 1905, the year Dialogues de Bêtes was published, was also the year Colette left Willy, and took to the stage.

Music Hall Days

Colette began acting in 1905 at a garden party organized by her friend Natalie Barney, with whom she had a brief affair. After taking lessons from acclaimed mime Georges Wague, she made her professional debut in 1906, in a short pantomime as a scantily-clad faun in Francis de Croisset’s Le Désir, l’Amour et la Chimère.

Willy, engrossed with a new mistress, suggested Colette go on a theatrical tour to get her out of the way. Instead she moved out altogether. “To ‘desert the domestic hearth’ was to us provincial girls of 1900 or so, a formidable and unwieldy notion, encumbered with policemen and barrel-topped trunks and thick veils, not to mention railway time-tables,” she later wrote in My Apprenticeships. But she had the assistance of her friend “Missy”—Mathilde de Morny, the Marquise de Belbeuf. Missy was a lesbian who Colette had met through Natalie Barney; she dressed like a man with boots, a cane, and top-hat, had lots of money, and was wild about Colette. The two became lovers and, in November 1906, Missy helped Colette move out from Willy’s into a flat of her own. She also followed Colette onto the stage.

In 1907 the two acted together in the mime-play Rêve d’Egypte at the Moulin Rouge, in which they exchanged a long kiss. Two women kissing in public was a heady thing in 1907, even in Paris; it started a riot in the theater and the police threatened to close the Moulin Rouge if it happened again. When Missy’s shocked family cut off her income, Colette had to make her own living—not as a writer but an actress. Willy owned the rights to the Claudine novels, and publishing new books was a shaky and uncertain way to make a living. And so Colette spent much of 1907-1911 working as a mime in the company of Georges Wague and Christine Kerf—in music halls in Paris and on tours through other major towns in France and Belgium. Their most successful production was probably La Chair, in which Colette bared a breast. Like Madonna and her younger imitator, Lady Gaga, Colette was an expert at the delicate art of fashionably shocking the public. Her famous “bared breast” was the subject scandal, praise, cartoon caricatures and humorous poems like this one from a Marseilles newspaper:

I saw La Chair! Now it might not be

Fine art, but I admit

Colette certainly has nice tits!

And anyone who likes knockers would agree!

For the women of Europe, it was a liberating moment. In her personal life, though, Colette struggled with the price of independence: loneliness, uncertainty and (for the first time in her life) the need to make ends meet. Her relations with Willy remained amicable (until 1909, when he infuriated her by selling the rights to the Claudine novels for a pittance) and she had Missy and some old friends who remained loyal, like Marcel Proust, Léon Hamel and the novelist Rachilde. Still, she had become isolated from polite society, a bête noir who wore the perfume of scandal. “I began to cry like an idiot,” she wrote Missy in a letter while on tour in Lyons, “because I have been so lonely for so long.”

Despite the rigors of acting and her supposedly lazy work habits, Colette continued to write. She published one more Claudine book, Retreat from Love (La Retraite Sentimentale, 1907), and a collection of stories, The Tendrils of the Vine (Les Vrilles de la vigne, 1908). But it was The Vagabond (La Vagabonde, 1910) that best sums up her music hall days.

Renée Néré is a recent divorcee who makes a living on the stage, acting as a mime with her mentor Brague (based on Georges Wague) at the Empyrée-Clichy music hall. She is haunted by the memories of her ex-husband, the artist Taillandy (an obvious write-in for Willy), who abused her, cheated on her, and even had her take his mistress shopping so he could make an assignation with another mistress. Now living alone in a flat with her dog Fossette, Renée leads a spartan existence; her only visitors are stage artists and her old friend Hammond (Léon Hamel), who himself is a victim of a philandering wife. Renée is, then, every inch a reproduction of Colette—she has even had novels published, though she is now too busy to write (“To write is the joy and torment of the idle”). Putting on make-up backstage, she meditates on her past and current circumstances.

Yes, this is the dangerous, lucid hour. Who will knock at the door of my dressing-room, what face will come between me and the painted mentor peering at me from the other side of the looking-glass? Chance, my master and my friend, will, I feel sure, deign once again to send me the spirits of his unruly kingdom. All my trust is now in him—and in myself. But above all in him, for when I go under he always fishes me out, seizing and shaking me like a life-saving dog whose teeth tear my skin a little every time. So now, whenever I despair, I no longer expect my end, but some bit of luck, some commonplace little miracle which, like a glittering link, will mend again the necklace of my days.

A new admirer, Monsieur Dufferein-Chautel (who Renée nicknames “the Big-Noodle”) arranges for her and Brague to perform at a private party in a sumptuous upper-class house. During the performance, the heroine finds herself looking at familiar faces in the audience.

Behind her I recognise another woman too ... and then one more. They used to come and have tea every week at my house in the days when I was married. Perhaps they slept with my husband; it does not matter if they did.

The Vagabond echoes the aftershocks of Colette’s separation from Willy (they officially divorced the year it was published). It is her most serious and, perhaps, profound novel. Written in the first person present tense—about a hundred years before it became fashionable—Colette channels Renée’s intimate thoughts and feelings as she weighs her independence against her increasing love of “the Big-Noodle”—and all the risks of another marriage. This is a far removal from the spirited and irreverent Claudine novels, solemn, meditative, and sometimes fatalistic—though there are still bright splashes of color here and there: love letters, Fossette’s lapdog antics, the painted actors talking shop before they take the stage, the jauntiness of a roving life:

All this is still my kingdom, a small portion of the splendid riches which God distributes to passers-by, to wanderers and to solitaries. The earth belongs to anyone who stops for a moment, gazes and goes on his way...

Erica Jong called The Vagabond “one of the first and best feminist novels ever written,” and if this had been Colette’s only book she might have become a feminist literary icon alongside Anaïs Nin and Virginia Woolf. But her sharp tongue (“I’ll tell you what the suffragettes deserve: the whip and the harem,” she was quoted in one interview) and the tendency of her female characters to be overpowered by their love for a man alienated her from the feminists of her own time. Their differences were perhaps irreconcilable—in order to win the vote and other rights, the suffragettes had to bury sexuality and stand up equally to men, while to Colette the only real power was in the bedroom and the fastness of the human heart, where men and women would always be different.

“Burnt child though you are, you’ll go back to the fire, you mark my words!” Margot, Taillandy’s spinster sister, warns Renée in The Vagabond. But Colette herself could not stay away from the flames. She had Missy, who nurtured her and bought her a house on the coast of Brittany near Saint-Malo, but she had by no means sworn off men. And her admirers in the music hall were many—rich young men stealing backstage to present the pretty thirty-something mime a bouquet of flowers and an invitation to a tryst or an exclusive gathering. Once, to discourage a would-be suitor who had been hanging about, Colette had the maid conduct him to her bedroom; then she got out of bed naked, ignoring her would-be lover, and, going behind her dressing screen, began farting until the shocked gentleman left.

Auguste Hériot, the rich and handsome young son of a department store magnate, was more successful. Colette was thirteen years his senior, and he followed her about like a puppy, driving her in his motor cars and staying with her in five star hotels. He took her to London, Naples, the Côte d’Azur. Though charmed by the passion and luxury in which she found herself surrounded, Colette would not marry him: Hériot’s inherent idleness and melancholy were incompatible with her own high-spirited nature. “He is a sweet child when he is alone with me,” she wrote Léon Hamel. “He will never be happy; his whole character is based upon an underlying sadness.” The two remained friends, however, and Colette would immortalize Hériot as the epicurean, pretty boy Chéri.

It was quite a different matter with Henry de Jouvenel. He was an editor-in-chief for the newspaper Le Matin. Colette’s success with The Vagabond (it was short-listed for the Prix Goncourt) meant that her writing was in demand, and she began penning columns and publishing stories in Le Matin towards the end of 1910. By the spring of 1911, Colette and Jouvenel were falling madly in love. She had to send telegrams to Auguste Hériot, forbidding him to come see her perform in Geneva, because Jouvenel would be there and she feared a duel. Colette’s life too was in some danger—from Jouvenel’s mistress, Isabelle de Comminges. Jouvenel could not marry Comminges because her husband was insane (he thought he was a dog) but the two lived as a married couple and had a son together; when Jouvenel admitted he loved another woman, Comminges swore she would kill her. In an excited letter to Léon Hamel, Colette writes that she was being guarded by a trio of Le Matin editors because “the Panther” (Comminges) “was still prowling around with a revolver and looking for me.” Then, suddenly, the Panther had gone—with, of all people, Auguste Hériot, departing on his yacht for a six weeks’ cruise “after having astonished their home port of Le Havre with their spectacular drunken parties. Isn’t that fine? Isn’t it theatrical? Really too much, don’t you think?”

After concluding her role as a femme fatale, Colette settled in comfortably with Jouvenel, and wound down her activities in the music hall in favor of working as a journalist. The couple were married in 1912, and in 1913 had a daughter named Colette, nicknamed “Bel-Gazou.” Colette’s nickname for Jouvenel was “Sidi” (“lord” in Arabic). Once more, as with Willy, she was in the fetters of love, and once more she felt jealousy and betrayal when Jouvenel, a famous womanizer, was frequently absent. Her next novel was a sequel to The Vagabond, appropriately entitled The Shackle (L’Entrave, 1913). As Natalie Barney wrote, “Torn between the desires of her two contrary natures, to have a master and not to have one, she always opted for the first solution.”

After the War

Although Colette saw little of Mathilde de Morny after 1911, Missy had deeded her Rozven, the house near Saint-Malo, as a gift, and she was there with Jouvenel and Bel-Gazou in the summer of 1914, until the guns of August ended their seaside idyll. Jouvenel was almost immediately called to active duty, and Colette followed him clandestinely to Verdun. She moved back and forth between the grimness of the front and Paris, which had become a city of women and rationing, until able to escape to Rome in 1915 as a journalist for Le Matin; Gabriele D’Annunzio, who was later one of her lovers, stayed in the room next door at her hotel.

Colette returned to Rome with Jouvenel in 1917—he on a diplomatic mission and she for the filming of La Vagabonda, an Italian adaptation of The Vagabond for which she wrote the screenplay; Colette was one of the first authors to be involved with that new medium, the motion picture. She eked out the remainder of the war in Paris and Rozven, and survived the Spanish influenza epidemic (though Annie de Pène died). But by the end of the war she and her second husband were drifting apart. Jouvenel had now become a successful diplomat and politician; he was part of the French delegation at the disarmament talks, became a senator for the Corrèze region of France, and later a delegate at the newly-formed League of Nations. Much of his spare time was devoted to liaisons with other women (one of his mistresses, Princess Marthe Bibesco of Romania, was, like Colette, a novelist). Colette meanwhile was entering her great era of literary production, starting with Chéri (1920), a short novel based on some pre-war stories modeled on the playboy Auguste Hériot.

Like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Chéri and its sequel, The End of Chéri (La Fin de Chéri, 1926), both glorify and condemn the excesses of the 1920s. The pampered son of Madame Peloux, a former ballet-dancer-turned-mistress, Chéri is dazzlingly handsome and dissolute. He has had a long ongoing affair with Léa, an old friend of Madame Peloux’s who is still a practicing member in the Parisian demimonde; but this is put in jeopardy when Chéri’s mother negotiates a match between him and Edmée, the rich young daughter of another courtesan. Sensual and cruel in the way of children, Chéri is also a victim of brooding melancholy. At one point, feeling lost without Léa, he deserts his newly wed wife and takes up residence in a hotel with a friend.

He ate and drank a lot, taking the greatest care to appear serious and blasé; but his pleasure was enhanced by the least sound of laughter, the clink of glasses, or the strains of a syrupy valse. The steely blue of the highly glazed woodwork reminded him of the Riviera, at the hour when the too blue sea grows dark around the blurred reflection of the noonday sun. He forgot that very handsome young men ought to pretend indifference; he began to scrutinize the dark girl opposite, so that she trembled all over under his expert gaze.

Like Jay Gatsby, Chéri is one of “the sad young men” of the Lost Generation who live passionately—but he lacks Gatsby’s magnanimity. Instead he is voluptuous and insatiable, delighting in the silk pajamas, pearls and baubles Léa showers him with, in the tradition of kept women and trophy wives everywhere. Indeed role reversal is a central theme in Chéri. “I devoured Chéri at a gulp,” André Gide wrote to Colette in a letter. “What a wonderful subject and with what intelligence, mastery and understanding of the least-admitted secrets of the flesh.”

Though Chéri is one of Colette’s most famous creations, the book is really told mainly from Léa’s viewpoint—and her dilemma is the same one that confronts Renée Néré in The Vagabond: choosing between the turbulent emotion of the heart and the clear wisdom of the mind. Alone in the quiet of her apartment, she knows that the better choice would be to let Chéri go and enjoy the remainder of his misspent youth:

With an effort she recovered her good sense, her pride, her lucidity. “A woman like me would never have the courage to call a halt? Nonsense, my beauty, we’ve had a good run for our money.” She surveyed the tall figure, erect, hands on hips, smiling at her from the looking glass. She was still Léa.

Perhaps this is why, when Chéri was attacked as vulgar and corrupting by the literary critics of the time, Colette responded in a letter to a friend “that I’ve never written anything as moral.” And Colette’s own morality was, about this time, being severely put to the test.

It was shortly after writing Chéri that she became close to Bertrand de Jouvenel, Henry de Jouvenel’s son from his first marriage. She was forty-seven and he was sixteen; nonetheless during summer holidays at Rozven, after Henry had gone off to Paris to meet one of his mistresses, Colette took it upon herself to indoctrinate Bertrand into the art of loving a woman. “I wrote Léa as a premonition,” she later said; years later, still feeling nostalgic about Colette, Betrand would write in his memoirs, “Perhaps she wanted to live what she had written.” Or revenge herself on Bertrand’s father for his numerous affairs. Whatever her initial motive, Colette and Bertrand held trysts whenever they could, and she even took him to Algeria with her.

When the affair became known, Henry de Jouvenel demanded a divorce, but he was not able to separate his son and his wife, and it was not until 1924 that Bertrand married Marcelle Prat (Maurice Maeterlinck’s niece) and stopped seeing Colette. He went on write political philosophy, interviewed Hitler in the ‘30s, and is now most famous for his quote “A society of sheep must in time beget a government of wolves.” Colette may not have taught him about wolves and sheep, but she did give him a thorough education in cougars.

As for Colette herself, seducing her stepson probably seemed no worse than kissing another woman or baring a breast on stage, though her novel Ripening Seed (Le Blé en herbe, 1923) suggests she did feel some culpability in the matter. Inspired by Bertrand de Jouvenel and a school girl his age who was, for a time, Colette’s rival, Ripening Seed takes place during summer holidays on the coast of Brittany. Phil and Vinca, adolescents whose families have shared a vacation home for years, are at the awkward stage of sexual awakening, still friends as they were in childhood but also becoming aware of their desire for one another. Their parents and the others who inhabit the home are “ghosts,” an element of the scenery but not really part of their world. Their intense relationship, at times broken up by play fights or quarrels, is thrown into crisis when an older woman in a neighboring estate, Madame Dallery, seduces Phil. The experience leaves him feeling emasculated, rather than manly—still he can’t resist visits to his mentor.

“Oh, she's gone away ... she's gone beyond recall. The woman who gave me ... who gave me ... How can I express what it was she gave me? There is no name for it. She just gave. She's the only person who's given me anything since my early days when Christmas used to be so wonderful. Yes, she gave me something, and now she's taken it away.”

Ripening Seed is one of Colette’s most evocative novels. Whatever happened in her real life, in the pages of the novel she places herself entirely in Phil and Vinca’s world, experiencing as they would the sea rocks and beaches, the unsettled subtleties of feeling and the way adults seem unreal and unimportant to young people of sixteen or seventeen. Her own character, Madame Dallery, is rarely seen and when she is, Colette paints her in an unflattering light.

She hastened with her charge towards the narrow confines of the shadowy realm where she, in her pride, could interpret a moan as an avowal of weakness, and where beggars for favours of her sort drink in the illusion that they are the generous donors.

Colette’s biographers are quick to contrast her unnatural closeness with her stepson to her apparent neglect of her daughter, Bel-Gazou, who was sent from nurse to boarding school for much of her childhood. In her book Colette, a Passion for Life, Geneviève Dormann describes Colette the younger:

I met Bel-Gazou when she was sixty. I am sorry that I did not get to know her better, as she was a lively, intelligent woman who had inherited her mother’s sense of humour. When anyone mentioned Colette to her, she remained strangely silent. One day, however, she told me, “I found my mother very intimidating.”

Whatever her private crimes, Colette the elder was, by the 1920s, being hailed as France’s greatest woman writer. She was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1920, and took part in Paris’ literary golden era. In 1922 she returned triumphantly to the stage, playing Léa in dramatic version of Chéri, which as a book had become a bestseller. It was also at this time that she began mythologizing her own life through a series of reminiscences and non-fiction, starting with My Mother’s House (La Maison de Claudine, 1922), a tender memoir about her mother. And her stories and newspaper articles continued to be published. “Colette was a pagan whose life and appetites were Olympian in their vitality, as was her oeuvre,” Judith Thurman writes in an introduction to the Claudine novels. If so, she mostly worshipped at Aphrodite’s altar. Reading Colette’s fiction from this era (in which, like as not, she appears in the narrative as herself) is a bit like listening to a friend whose sole topic of conversation is rehashing her failed relationships, or tuning in to Loveline. “Everything you love strips you of part of yourself,” Colette writes in “Bella-Vista”, a story about eccentric innkeepers at a seedy establishment on the French Riviera. For all that, she was not too embittered to love again, or feel things deeply. As she wrote to her friend Marguerite Moreno in 1923:

It is so strange, you successfully fight back tears and bear up well at the most difficult times. And then someone gives you a friendly wave from behind a window [...] a letter falls out of a drawer—and your whole world falls apart.

Nostalgia

It was around 1925 that Colette first met Maurice Goudeket, a dealer in precious stones who was become her third husband (though the two did not officially mary until 1935). Her last affair was by far her gentlest; she refers to Goudeket, sixteen years her junior, as “my great friend” in her meditative and autobiographical Break of Day (La Naissance du Jour, 1928).

Under Goudeket’s influence, Colette’s life reached calmer waters. She sold Rozven and they bought a house in Saint-Tropez on the Riviera, La Treille Muscate. Later she took an apartment in the Palais Royal, which was to remain her Paris residence until the end of her life. Her works from the 1930s include The Pure and Impure (Le Pur et L'Impur), a “novel” that is really a dialogue between characters about their sexual experiences and predilections (Colette thought it was one of her best books—the critics begged to disagree) and La Chatte (a man loves his cat more than his wife). Aside from a failed business selling beauty products, the Great Depression mostly spared her—though an arthritic hip began curtailing her travel.

When the Germans invaded France in 1940, Colette and Goudeket at first went to a ruined castle near Castel-Novel; it had been inherited by her daughter Bel-Gazou, who later took part in the Resistance. But boredom and privation eventually led them back to Paris. Goudeket, who was Jewish, was arrested near the end of 1941 and sent to a prison camp in Compiègne. Colette moved heaven and earth to gain his release, calling on friends such as Sacha Guitry, Coco Chanel and José Maria Sert. Sert, who was (or pretended to be) friendly to the Nazis, was able to get Goudeket released, and for the rest of the war he lived the life of a fugitive. Colette recalls the German occupation vividly in one of her last memoirs, The Evening Star (L'Étoile Vesper, 1947):

Sustained by a hunted companion, and then deprived of that same companion when in prison, I took my place in the ranks of the host of women who waited. To wait in Paris was to drink from the spring itself, however bitter.

During the last eighteen months he whom I call my best friend would leave our roof every night to go and sleep, here, there, everywhere, his peaceful sleep of the condemned.

Colette herself watched most of the war from her apartment in the Palais Royal (one of her neighbors was Jean Cocteau). Racked by pain in her hip and missing Goudeket, she withdrew into herself, and lived through her memories. Her last works have a nostalgic atmosphere, set in a pre-war France where the only worries one had were money and a broken heart. Yet even looking back into the past in her old age, Colette’s stories are filled with a lively immediacy; while her friend Marcel Proust viewed the world through refined distillations of memory, she wrote in the furnace of the moment.

Chance Acquaintances (Chambre d'hotel, 1940) is set at a resort in the Alps, where Colette meets a husband and wife whose characters are a study of contrast (the wife a decent, homely sort; her husband a besotted fool with a mistress in Paris). Her friend Lucette, from whom she is renting her chalet, is a character right out of Chéri or The Vagabond, and with her usual nuance Colette describes the precarious circumstances belonging to women of the demimonde:

From acting at the Olympia for Paul Franck, she suddenly found herself playing third-rate provincial stands in the off-season. Then, all of a sudden, one would see her driving up to the Moulin Rouge in a carriage-and-pair.

“I’m leaving for Saint-Petersburg,” she once confided to me. Then, thinking of all the risks and fatigues that lay ahead, she added, “What must be, must be.”

Julie de Carneilhan is a more ambitious work, based on Colette’s relationship with Jouvenel following their divorce, while “The Kepi” (“Le Képi”, 1943), draws on her early days with Willy, when an older friend fell in love with a young lieutenant. But her finest work from this period (and to English readers, the best-known of all her titles) is Gigi.

“Put on your hat, Gigi! I’m taking you out to tea.”

“Where?” cried Gigi.

“To the Réservoirs, at Versailles!”

“Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!” chanted Gilberte.

She turned towards the kitchen.

“Grandmamma, I’m having tea at the Réservoirs, with Tonton!”

Madame Alvarez appeared, and without stopping to untie the flowered satinette apron across her stomach, interposed her soft hand between Gilberte’s arm and that of Gaston Lachaille.

“No, Gaston,” she said simply.

“What do you mean, No?”

“Oh! Grandmamma!” wailed Gigi.

Madame Alvarez seemed not to hear her.

“Go to your room a minute, Gigi. I should like to talk to Monsieur Lachaille in private.”

Gigi (1944) is the classic story of naiveté triumphing over guile. Gigi, a girl of fifteen who still retains her childish exuberance, is hopelessly clumsy; the arts of allurement are entirely foreign to her. She lives with her mother (a theater singer who is seldom present) and her grandmother, Madame Alvarez, a retired courtesan. How the playboy Gaston Lachaille, a rich young sugar baron, is connected to the family is never explained, though it is possible Madame Alvarez was his father’s mistress:

From her former relationship, real or invented, she drew no advantage other than the close relationship of Gaston Lachaille, and the pleasure to be derived from watching a rich man enjoying the comforts of the poor when he made himself at home in her old armchair.

The era in which the story is set is also quite vague, though it seems to be closer to World War I than II. In any case wars are entirely absent from the novel, and Gaston’s spontaneous courtship of Gigi comes off as charming rather than foolish; hardly a taste of bitterness can be found in its short narrative (65 pages in my edition—most writers would need over 200). For all it’s liveliness, Gigi is a quiet novel. At the calm center of the story is the good-hearted Madame Alvarez, with her shabby but comfortable rooms and her camomile tea. Perhaps it was Colette’s way of keeping everyone’s spirits up during one of the darkest chapters of French history.

As so much of Colette’s fiction has a real-life parallel, it is tempting to read into Gigi. Is the character of Gigi based on Bel Gazou, and is Gigi’s often-absent mother a portrait of Colette herself? Is Madame Alvarez based on Colette’s much-beloved mother? Or is she the mother Colette herself wished she had been? Whatever Gigi’s antecedents, she was Colette’s last gift to her readers.

To the stage, however, she had one more treasure to bestow. In 1951, on a visit to Monte Carlo for her health (nearing 80, she was in almost constant pain from arthritis), Colette was in her wheelchair in the lobby of the Hôtel de Paris when she happened to see a scene from the film Monte Carlo Baby being shot. She was looking for someone to play the role of Gigi in an upcoming Broadway adaptation, and when she saw an unknown actress named Audrey Hepburn, who had a small part in the film, walking across the hotel lobby, Colette whispered to a friend, “Voila, there's my Gigi!” She lived to see Hepburn in the Broadway production, though not the Learner and Lowe film version.

Upon her death in 1954 Colette was given a state funeral—the first woman in French history to have one—and buried in Père Lachaise. She shares a cemetery with Édith Piaf, an artist whose life (and taste in younger men) resembled her own. Colette wrote about heartbreak, and Piaf sang about it, but neither woman was able to turn away from love for long. As Gigi put it to Gaston: “I’ve been thinking I would rather be miserable with you than without you. So...”

The quotes give above were from the following translations: Claudine at School and Claudine in Paris: Antonia White; The Vagabond: Enid McLeod; Cheri, Ripening Seed and Gigi: Roger Senhouse; The Evening Star: David Le Vey; Chance Acquaintances: Patrick Leigh Fermor;

For further reading: I would highly recommend Geneviève Dormann's opinionated but lively and highly accurate biography: Colette, A Passion for Life, from which the above letter excerpts are taken.