Once More Around the Bloch

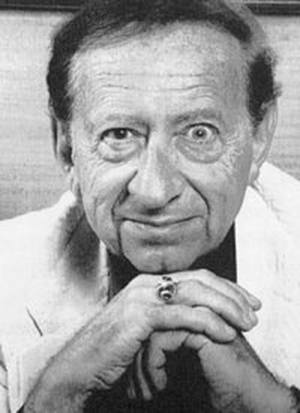

The Man Behind the Fright Mask

by Thomas R. Smith

When I was fourteen, in October, 1962, I wrote a fan letter to Robert Bloch, the author of, among many other pieces of horror, suspense, and science fiction, the novel that soon became known as “Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.” Bloch, who had recently relocated from Wisconsin to Hollywood, generously and kindly obliged me with a reply, opening the door to an almost monthly correspondence for the next year and a half. Because of his encouragement--and that of another sometime-horror writer, August Derleth, incidentally also the publisher who resurrected H. P. Lovecraft from pulp magazine oblivion--I received validation for thinking of myself as a budding writer at a formative age.

Those encouragements are a story I must tell elsewhere, but they lie in the background of this essay, which is a late attempt to see my old mentor beyond the blinders of my adolescent hero-worship and in the light of what has endured to become a life-long gratitude. More and more I am interested in that provocative question: Who exactly was this man who customarily donned the fright mask when he sat down to write?

In his “unauthorized autobiography” (what a kidder!), Once Around the Bloch (1993), Robert Bloch confessed that, despite an abundance of psychiatrist characters in his fiction, he himself had never undergone psychotherapy.

It’s true that Bloch had little inclination, at least in print, for self-analysis. No doubt he found it odious, though perhaps unintentionally comic, when others yielded to the temptation to psychoanalyze him. While I’m loathe to cross that line myself, I feel a strangely delayed urgency, more than five decades after the fact of our correspondence, to focus more clearly on who exactly this writer was, as a person, who so influenced me at an impressionable age.

In addressing this question, I must first acknowledge the core of his popular appeal as a writer of horror fiction. A glance at the titles of some of his books in the early Sixties, his heyday as “author of Psycho,” tells the story with admirable economy: Terror, Tales in a Jugular Vein, Blood Runs Cold, Bogey Men, Atoms and Evil, and Horror-7, to name a few. From his first published stories in the legendary Weird Tales at the age of 17, this is the territory Bloch staked out: murder, grue, suspense, shock, fear. On the face of it, Bloch’s opus constitutes a remarkably consistent assault on socially accepted mores or what we could call our “day-side” values. Bloch, it would seem, belongs to that group of writers whose principal aim is to project into their fiction the “night side” of human personality. In this, of course, he was hardly alone: the whole field of mystery, suspense and horror writing is a virtual exploration, sometimes a covert celebration, of what C. G. Jung calls the “shadow,” his term for the repository of those undesirable qualities in ourselves at odds with the dominant (though often hypocritically unacted) values of society.

Young people, who often perceive more sharply than compromised adults the contradictions of society, gravitate instinctively toward writers such as Bloch who expose the darkness, cruelty and destructiveness our convenient lies conceal. Bloch was sympathetic to this desire on the part of youth to penetrate the veil of comforting untruths, for deep at the heart of the apparently nihilistic horror writer, and his long, gory romp through the pulps, lay a seriousness of purpose easy to miss in the dark dazzle of his Grand Guignol theatrics. An outraged moralism was in fact the secret engine driving Bloch’s more truly horrific fictional machinations.

A glance at Bloch’s family life and childhood may be helpful here. One of the most touchingly persistent notes sounded in his autobiography is his love for his parents, Raphael and Stella Loeb Bloch, who fought for dignity and economic survival in Depression-era Chicago. Of German-Jewish extraction, Ray worked in banking and Stella was a teacher and social worker. Contrary to what Robert Bloch’s many unhealthily mother-fixated creations (of whom Norman Bates, the twisted amateur taxidermist of Psycho, is the most notorious) might lead us to expect, Bloch doesn’t appear especially mother-obsessed in his memoir. Still one notices an unmistakable change in tone when he writes of his parents; the genial, otherwise omnipresent punning humor drops away and a sober and serious filial piety dominates these passages, hinting at depths of feeling Bloch doesn’t ordinarily reveal.

Bloch’s mother dedicated much of her life to social services and charity, for many years assisting newly arrived Eastern European immigrants at Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln House. She is one likely source for the outspoken passion for equality and justice often detectable in even Bloch’s more frivolous entertainments. His portrait of the aftermath of nuclear disaster, “Daybroke” (1958), for instance, stands as an acid indictment of the self-defeating stupidity of war. “The Funnel of God” (1960), one of his most powerful tales, serves in part as a vehicle for his condemnation of South Africa’s apartheid. “The Warm Farewell” (1970) reserves some of Bloch’s most concentrated venom for a Klan-like white supremacist group called the White Hopes. And even in a sensational thrill ride like the neo-Lovecraftian “Terror in Cutthroat Cove” (1958), the narrator obviously speaks for the author when he sharply rebukes another character’s reflexive racism.

In fact, Bloch’s work as a whole is laced with a more or less audible outcry against the inhumanity and violence the mordantly witty writer witnessed in the world around him. Bloch clearly loathed and feared the human capacity for evil he anatomized in his fiction, often with the insightfulness of a psychotherapist. Fear, he once wrote, “forms the basis of all my work...” Yet reading even his most calculating chillers, one understands that the terrors of which Bloch writes are not the ones he fears most. Indeed, Bloch makes clear in the introduction to his collection The Living Demons (1967) that the reader is not intended to be traumatized by his nightmares: “...these creatures have no power to harm you. On the contrary, they were dug up only for your entertainment.”

So what did Robert Bloch truly fear? In his memoir, he is frank: he fears the ordinary terrors that haunt us all--disease, old age, death, the loss of those dear to us. He possessed an extraordinary degree of self-awareness even in childhood. This sensitivity registers poignantly Bloch’s dawning consciousness of mortality:

The hardest thing to realize, let alone accept, was the fact that someday Mama and Daddy would die too, leaving me and my sister alone. What could we do without them? When directly confronted with the possibility, they admitted that this would happen someday, though by then I’d be a grown-up myself and able to cope. But I didn’t want to cope, and I didn’t even want to imagine a world without my parents. Death was something that happened to other people, not to my loved ones.

Bloch despised the violence and cruelty of which human beings are capable, yet his chief adversary is not human: it is the universe. In the tale of terror, whether of human or supernatural agency, Bloch discovered the ideal medium for venting and to some extent exorcising his existential dread, not of death only, but also of the ordinary terrors of living. In this, we can draw a clear kinship with his mentor Lovecraft, who elevated his distrust of life to heights of cosmic paranoia in his grandiose fictions.

It’s not surprising that an acutely sensitive and intelligent youth should turn to the horror tale as a means for keeping under control a deeply and personally felt fear of mortal loss. As I discovered as a teenager, what worked for Robert Bloch worked, though on a much more limited basis, for me as well: symbolic confrontation with fear through stories--especially those I wrote myself--crucially eased or diminished those fears and allowed me to flourish despite them.

The reader who has not had the pleasure of experiencing Bloch, who may know him only by reputation, may be surprised to learn that Bloch is by no means a grim and cheerless character. Earlier I alluded to Bloch’s irrepressible sense of humor, a force to be reckoned with in his work. In fact, as a young man, Bloch aspired to become a stand-up comic. Those who heard him speak at science fiction conventions, at which he was a frequent and popular guest, have amply testified to his wit and sense of timing. That wit seasons even his darkest stories. As a comedian, he naturally drove toward the punch line, and often he did the same in his fiction, a practice he admits marred some of his efforts with overly contrived endings. Humor and horror are mutually obsessed with endings. Old-time fans still revere a series of stories Bloch wrote in the Forties featuring a wise-cracking, zoot-suited character named Lefty Feep. Unlike anything else in his body of work, the Feep stories are built around shaggy-dog puns and hilarious situations. They’re more marvelous for having been written in an unhappy period in Bloch’s life, marked by financial insecurity and family medical worries.

On the down side, in Bloch’s memoir we witness a tendency to retreat from strong emotion, especially of the more tender sort. Of the death of his beloved mentor H. P. Lovecraft, he says only: “There were no words to acknowledge my grief then and there are none now.” Bloch sounds this note of dumb-struck finality with some frequency. Perhaps he found it too painful to plumb those profound griefs in public. “Profundity was never my province,” he wrote in 1977, though profundity was undoubtedly in him.

He remains, for me, two decades after his death, a sometimes enigmatically contradictory figure. Recently I re-read nearly a hundred of his stories, and noticed especially his penchant for revenge fantasy. In nearly every one of his more earnest efforts, a morally unsavory or downright evil character meets with a poetically just doom. One can only surmise as to the enduring appeal of this approach to the author over the span of his writing career. Does it bespeak a persistent sense of powerlessness that required frequent symbolic redress by way of his fiction? Was there an element of the powerless “little man” in Bloch’s psychological make-up that demanded a continual purging via fantasy? Was it for this passive, perhaps “feminine” part of Bloch’s own personality that justice must be won over and over again, in one revenge scenario after another?

Though such questions may be unanswerable, I believe that an introduction he wrote for his first book, The Opener of the Way (1945), offers at least a clue. Elaborating on a long-standing fascination with the psychic duality represented in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the 28-year-old Bloch posits as explanation (apparently not tongue-in-cheek) for his preoccupation with dark matters, a Jekyll/Hyde split in himself. The mild-mannered Jekyll, he says, supplies the speaking voice and niceties of style in his work, but the content comes courtesy of Mr. Hyde.

...Mr. Hyde is definitely responsible for the basic theme underlying the stories as a whole ... the logical insistence that unpleasant consequences await anyone who meddles in affairs best left undisturbed.

... I can only submit that this is a matter beyond my control. If, some time, I can write a tale dictated entirely by the conscious personality of Dr. Jekyll, the result may be entirely different from any effort presented here. But, barring this possibility, the works published under my name will continue to exhibit the hideous handiwork of Hyde.

Ranging again through my prolific old mentor’s work, I’ve become increasingly interested in those scattered instances in which Bloch allows the humane and compassionate Dr. Jekyll to speak. Though in his earlier Lovecraft-dominated output Bloch is firmly under Hyde’s direction, his inner Jekyll becomes most audible in his stories set in the Hollywood motion picture milieu, which he loved. “The Movie People” (1969) is as close to a straightforward love story as we’ll find in his sprawling bibliography.

I consider it a matter of some regret that the Dr. Jekyll voice in Bloch never enjoyed full expression in the course of a productive and varied writing career. Though it’s tempting to blame the marketplace’s greater appetite for Hyde’s shadow-antics, I suspect the answer lies elsewhere. Bloch’s professed inability to balance Jekyll and Hyde in his writing (though apparently not in his life) indicates a wounding, perhaps manifested also in Bloch’s tendency toward self-deprecation. His writings provide ample if sporadic evidence that he could have become a more literary writer, but despite his erudition and intelligence, Bloch seems to have suffered an inferiority complex in respect to more “serious” writers.

Having come up against the limits of my ignorance, I’ll not speculate further, in hopes that Robert Bloch’s shade will forgive this brief, probably fruitless excursion into analysis. It seems inarguable that his demons were more formidable than his temperate manner betrayed, and that he wrestled with them honorably, in the process giving scary pleasure to millions and also putting food on the table for his family. In a sense, his entire oeuvre is a fascinatingly dark and always entertaining self-analysis, in which the alert reader is occasionally privileged a glimpse of the essentially vulnerable, generous and kind man behind the fright mask.