| <- Back to main page |

(Grove Press)

The late novelist David Foster Wallace famously lamented contemporary culture’s obsession with irony. To Wallace, postmodern American literature and culture was characterized by a frenzied need to deconstruct, mock, criticize, and cut down. Although art and entertainment employing heavy irony may at times be quite funny (think Simpsons and Seinfeld), Wallace believed that irony had gone from liberating to enslaving. If all you do is mock and tear down, what is left is an empty black hole of meanness, meaninglessness, and despair.

If irony is the literary curse of postmodernism, what is the cure? For Wallace, the cure was sincerity. To see the good in things and in other people. To stop naval gazing and recognize the value of self-gift. In his 2005 Kenyon College commencement address, he distinguished the supposed freedom to be “lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the center of all creation,” with the “really important kind of freedom involv[ing] attention and awareness and discipline and being able to truly care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.”

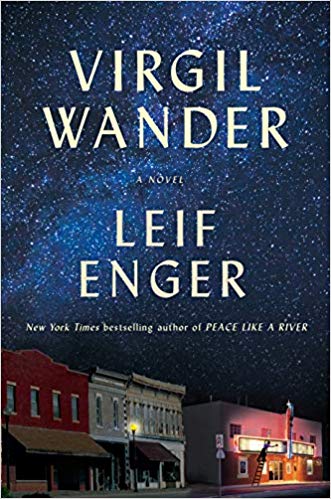

It is through the lens of this dichotomy between irony and nihilism on the one hand, and sincerity and self-gift on the other, that I propose one should read Minnesota author Leif Enger’s beautiful new novel, Virgil Wander. This is Enger’s third novel, his first, Peace Like a River, becoming a surprise bestseller in 2001. Any reader of Enger knows that he is no postmodernist writing for cheap laughs as he tears apart the sacred universe. Rather, Enger writes with a sincerity and a grace that reveals not only his depth at understanding and expressing human suffering, loss, and uncertainty, but also his faith in human goodness and redemption. To borrow a line from a Hopkins poem, Enger understands the “dearest freshness deep down things.”

At its core, Virgil Wander is a pilgrim’s story exploring the title character’s quest to rediscover meaning and direction in a life that has become aimless. The novel opens with the title narrator’s assessment of his life just prior to a car accident that plunged him and his car over a cliff and into stormy Lake Superior. We learn that Virgil lives in tiny Greenstone on the Minnesota North Shore where he operates an aging movie house, works part-time as a local bureaucrat, and for fun wanders alone photographing northern storms. While the accident has jarred him and diminished his lexicon, he acknowledges that even before the accident “the picture was unspooling all along and I just failed to notice.” Indeed, we learn later that the “accident” perhaps was no “accident,” but was likely an act of attempted suicide. What exactly caused Wander to go over the edge, so to speak, is left unclear; but what is clear is that the event served as a moment of grace. For as his physical being was resurrected out of the icy waters by a salvage man, his spiritual life likewise reawakened when he was released from the hospital and met retired Norwegian widower Rune Eliassen:

If I were to pinpoint when the world began reorganizing itself—that is, when my seeing of it began to shift—it would be the day a stranger named Rune blew into our bad luck town of Greenstone, Minnesota, like a spark from a boreal gloom. It was also the day of my release from St. Luke’s Hospital down in Duluth, so I was concussed and more than a little adrift....

I ended up at the waterfront. It’s not like there’s any other destination in Greenstone. The truth is I moved here largely because of the inland sea. I’d always felt peaceful around it—a naïve response given its fearsome temper, but who could resist that wide throw of horizon, the columns of morning steam? And the sound of a continual tectonic bass line. In a northeast gale this pounding adds a layer of friction to every conversation in town.

At the foot of the city pier stood a threadbare stranger. He had eight-day whiskers and fisherman hands, a pipe in his mouth like a mariner in a fable, and a question in his eyes. A rolled-up paper kite was tucked under his arm—I could see bold swatches of paint on it.

There was always a kite in the picture with Rune, as it turned out.

He watched me. He carried an atmosphere of dispersing confusion, as though he were coming awake. “Do you live in this place?” he inquired.

I nodded.

Rune serves as an important guide and father-figure to Virgil Wander, akin to the role a different Virgil played to Dante during his travels to Hell and Purgatory in The Divine Comedy. Both are middle-aged and midway through their life’s journeys; some event or series of life circumstances have left them wandering from truth; and they now find themselves asleep, aimless, and perhaps willing to drive off a cliff to experience death which seems “hardly more” than the suffering and banality of life. What is Dante’s road back to the straight and true? Not an isolated quest at self-discovery, a descent into the prison of a “tiny skull-sized kingdom,” but rather, a journey away from self and toward friendship, self-gift, and the communion of saints. And this journey away from lonely despair necessitates receiving and being guided from without—for Dante, being guided by Virgil and then Beatrice into the very heart of the Father’s love—and for Virgil Wander, in turn being guided by and guiding a host of lonely characters, including Rune, Rune’s daughter-in-law, Nadine, Nadine’s son, Bjorn, and local truant Galen.

Although these characters are diverse in age, personality, and life experiences, they all share one thing: a sense of aloneness. Virgil lives alone in a small apartment above his movie house, burdened by deep guilt and shame for not being with his parents when they died in a train derailment in a Mexican canyon while serving as Christian missionaries when he was 17. Rune is likewise alone, the “final post” in his family lineage. His wife is dead. His sister is dead. And he previously lived alone in Tromsø, Norway, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. Nadine’s husband, Alec Sandstrom, mysteriously disappeared more than a decade before in a solo flight over Lake Superior. Although she lives with her teenage son, Bjorn, both find it increasingly difficult to relate to one another. Because of the loss of his father, Bjorn “lost the ability to imagine the future”; and although he is “counseled, exhorted, drugged,” he is without hope and chooses to be alone much of the time. Finally, 10-year-old Galen Pea, recent orphan after his father drowned in Lake Superior, is isolated from his peers, who all own Xboxes, whereas Galen “fished alone.”

While these characters begin the story alone, at least in their minds, they do not end that way. Rune takes the part of adoptive father to Virgil, flying magical home-made kites with Virgil over Lake Superior like a father with a young child. Virgil in turn assumes a fatherly role for both Bjorn and Galen. At one point, Virgil silently observes Bjorn from a distance and suddenly has the experience of being “answerable.” What Virgil is expressing is man’s need to focus not simply on the self, but also on the responsibility owed to others; a responsibility that is both a burden and a blessing.

What Enger gives his readers in the end is a landscape of good. Certainly the book also contains death and loss and suicide; perhaps also murder and attempted suicide and evil spirits (or at least evil people) that prowl about the world seeking at least the physical death of people, if not the ruin of their souls. But it is more fundamentally about the underlying goodness of things; in particular, the underlying goodness in human connection. That the way to counter the aimless life is not to wander inward, but to gaze outward. It is also about the necessity of place; that real human community does not happen in some airy spiritual existence, but between real humans, with real flesh and bones, who live in real houses, on real streets, surrounded by real woods, and grass, and seas. He portrays a humanity that is both fallen, and yet redeemed. That is not hopeless. That does not have all the answers, yet is willing to be silent; to sit in wonder; to accept the beauty and goodness that is present; and to find rest and meaning in that beauty and goodness. Perhaps Virgil the narrator sums it up best when he looks with eagerness at Bjorn’s upcoming 18th birthday party: “What a relief, the thought of a warm kitchen, the giving of gifts, the awkward singing and generational strain. How gorgeous and lush and difficult.” Yes indeed, such is life, gorgeous and lush and difficult.

- Jeffrey Wald