| <- Back to main page |

by Steven Masterson

Although this is a true story, some names have been changed to protect the guilty, and some scenes and dialogue have been recreated.

“Hey, leave her alone; get the hell out of here!” I yelled as I leapt from my bar stool to the floor, hoping my drunken legs would not betray me. I had seen him come in; he was shorter than I but bigger. He’d burst through the door, letting that hellish sunlight in behind him. With a threatening scowl on his face, he headed straight for the corner of the bar where Maggie, the barmaid, had set up shop. That scowl was now leveled at me. He’d been arguing with Maggie, and she had been holding her own. Just a lover’s quarrel, I’d said to myself and had gone back to my world in a bottle. Then he slapped her. Even in my darkest days, I knew that wasn’t right. So there I stood, barely standing, swaying in a nonexistent breeze in a bar suddenly gone intensely quiet, fifteen feet away from, yet face to face with, a man built like a fire hydrant. His eyes were trying to burn a hole through my head. Why, I said to myself, will a drunk’s legs never act in his best interest? He didn’t blink. I tried to stand still. Abruptly he turned and went in the same straight line to the door and opened it, letting in that damn sunlight. The door closed behind him. My legs continued to wobble. “Screw you,” I said to them, shakily regaining my stool. I was sitting at the bottom of a U-shaped bar. Scattered about the two legs were five or six other guys. When that damn sunlight was blocked out for good, their silence ended.

“Are you crazy?”

“What the hell are you doing?”

“Don’t you know who that is?”

That one got my attention. I didn’t know who he was. I mean I figured he was Maggie’s boyfriend, but I’d never seen him before or heard her talk about him.

“No. Who is he?” They found this to be seriously funny. The guffaws and bar-banging made some people’s day.

“Well, who the hell is he?”

“That’s Tommy O’Rourke. He’s a hit man for Patriarca,” laughed the big guy sitting safely way up on the right-hand leg. They loved the look on my face.

If I was sober I could have felt my adrenalin draining; instead I felt Maggie’s hand on my arm. “Don’t worry, I’ll talk to Tommy; and thank you.” Worry? Why should I worry? The woman who just got slapped is going to talk to the hit man so I don’t get whacked. Cool. I finished my beer and left the bar.

A few days later Sheila, the love of my life, and I sat on adjoining bar stools and discussed, with slurred words, getting something to eat. It was a Friday and, being good Catholics, fish and chips was the preferred meal. Long gone were the days of takeout fish and chips lovingly unwrapped from greasy newspaper and eaten with fingers, so we decided on the Spinnaker Lounge, a bar that served food. It wasn’t much of a place, stuck between the freeway and the river, but the food was good; it wasn’t far and they had beer. These were the days before strict laws for drunk driving, and the weight of political correctness had not yet settled on our collective shoulders. So we jumped into the car and away we went. Fish and chips.

The Spinnaker was nobody’s family restaurant. At least nobody’s family that you would want to be part of, but Sheila and I weren’t a family yet, and it was okay for us. In previous incarnations it had been a gay bar and a discotheque, and it still had some of that same scruffy feel. We enjoyed being close to the edge, so it became our Friday night eatery. This night the edge got a little too close.

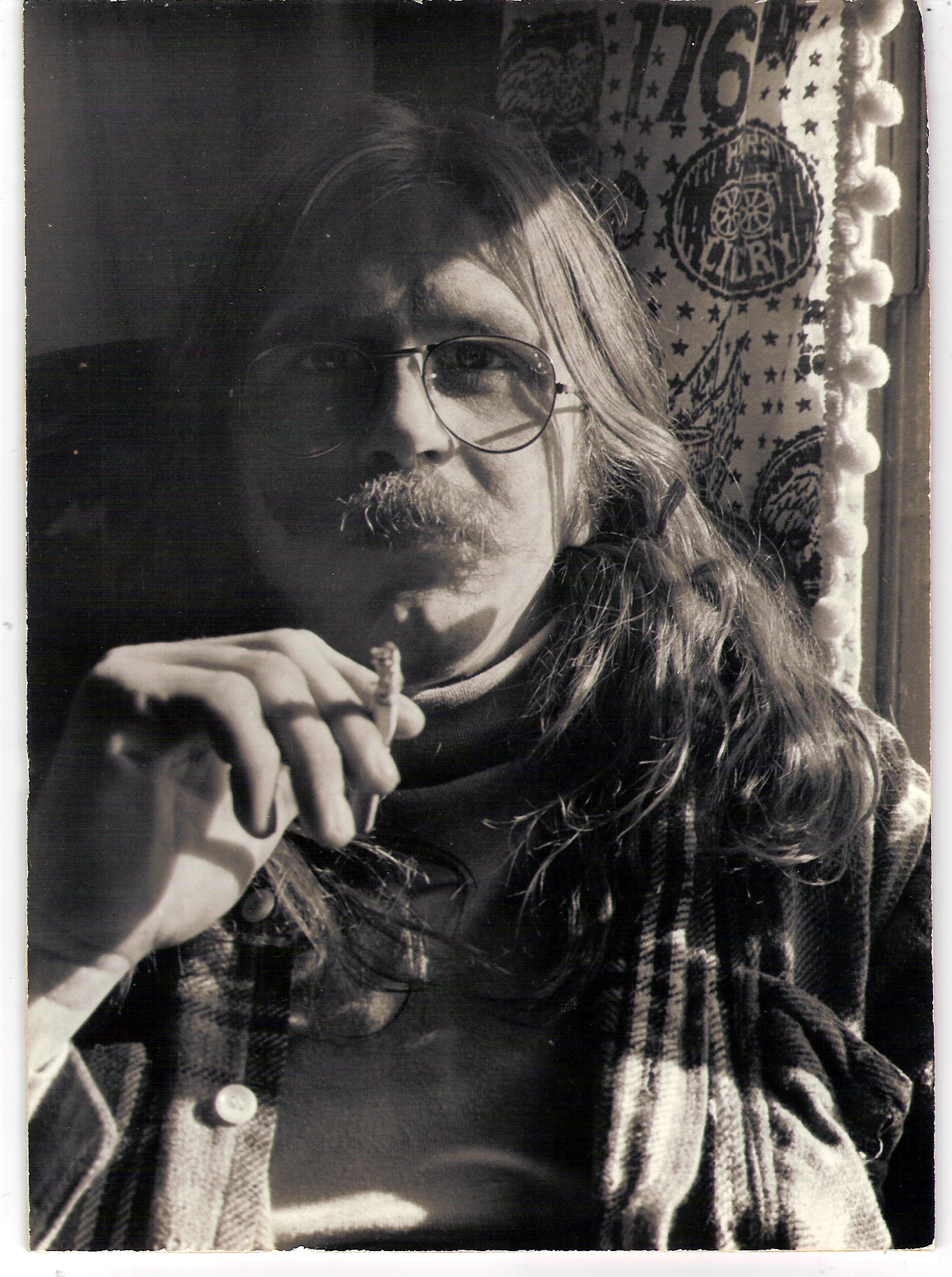

Now, I wasn’t always the well-groomed, handsome man I am today. Back then I looked closer to David Crosby than Tom Cruise, with a big, droopy handlebar mustache and a ponytail that reached halfway down my back. But I was comfortable. Tonight I was even more so with my hair down, a slight stumble in my walk, and a beautiful woman on my arm. She poked, pushed, and prodded me toward the door and those great fish and chips.

“You can’t come in,” the bouncer said.

“Why not?” snarled my never passive bride-to-be.

“You’ve got jeans on. No jeans on Friday nights.”

“Bullshit. We’ve been here every Friday night for the last two months and wore jeans every time. Everybody in the place had them on.”

“New dress code.”

“Dress code? We’re in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, between the highway and the river. Dress code? You’re out of your mind!”

I could see this was going to get ugly. Maybe already had. The fish wasn’t that good. “Come on, Sheila,” I said, grabbing her arm. “Let’s go to the Blue Bonnet.”

“No!”

“Yes.” I poked, pushed, and prodded her to the car. You have to pick your battles, and this wasn’t one I wanted to fight.

We both knew this wasn’t about jeans. It was the Seventies and the country was split. The counterculture was in full swing, and the right-wing pseudo-patriot faction was steadily losing moderates. This was about hair. About me “letting my freak flag fly” [David Crosby] and running into a dumb-as-a-stump “America: love it or leave it” patriot with a little power. I had run into it before and caught on right away, but I was surprised by Sheila. Young, tall, good-looking white women do not usually run into prejudice, except through religion, but she had caught on too.

“Steven, it’s your hair. We’ve never been here with you looking like that.”

“Thanks a lot.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Yes, I do. Let’s go to the Blue Bonnet.”

Sometimes God plays tricks with us. You could call His jokes fate or destiny, but mostly He just needs a good laugh. He chose this moment to poke us with a stick. Four short-haired guys wearing jeans walked into the Spinnaker and didn’t come out.

“Did you see that?’ she said.

“Yeah, let’s go to the Blue Bonnet.”

“No.”

“Sheila…”

“No, Steven, we can’t let them get away with it.”

Like I said, this was not a battle I wanted to fight, but there wasn’t much I wouldn’t do for this woman. So back to the door we went.

“I told you guys to get lost,” said the bouncer with a menacing look in his eyes.

“Those guys you just let in had jeans on.”

“No, they didn’t.”

Sheila was doing the talking, and I was watching the guy, ready to provide muscle. God was poking me with a stick again. My legs were behaving but my eyes never saw it coming. Damn them.

Regaining consciousness in the back of a paddy wagon is not exciting. Even if it is co-ed and you’re with the woman you love. A pounding head and a bloody face make it difficult to be romantic. Except for the flames burning in her eyes and her pure, awesome anger, Sheila was all right. She was beside herself, or was that my deceitful eyes? Closing the suckers, I asked Sheila what had happened.

“They met us up the steps just inside the door. I was blasting him about the jeans and your hair. I called him an idiot and poked him in the chest to make my point.” Her mother taught her how to emphasize. “I never saw the guy who hit you until he already had. I was shocked. You went down the steps and onto the sidewalk. They must have called the cops before we even went in; they almost caught you falling on your way out the door. Then they arrested us and hustled us into the wagon.”

There are any number of cut-and-paste charges police use to maintain control. I ran down the list in my head. Trespassing, drunk and disorderly, and disturbing the peace could all be used. These are hard charges to fight; the fine is less than the lawyer’s fee, and proving them against two people who have been drinking is a slam dunk. I didn’t think there would be a possession charge because we were clean. So it looked like a fine, a continuance without a finding, or some combination. All right; we could handle that.

We were charged with assaulting a police officer. The bouncer was an off-duty cop. That’s not good. That one doesn’t go away. That’s not God with His stick. That’s the City of Pawtucket with a two-by-four. It’s not a charge you want a cop you’re dealing with in the present to be reading about in your past. They hold a grudge. The same people who don’t believe in the thin blue line and all of its implications nod knowingly when a cop killer doesn’t make it to trial or even through the arrest. Resisting. Cut and paste. We were in trouble. It was a hard charge to beat. Sheila didn’t poke a cop. She poked a bouncer. I had assaulted no one; innocence doesn’t help.

We thought a drink would. A car accident, getting into a fight, or getting arrested can all be red badges of courage in certain environments. Our bar was one such place. Of course the severity of the accident, fight, or charges determines the quality of the badge. We wanted a judgment on ours. We wanted to tell our story. We did. Nobody was surprised by it. They, too, knew what it was about. We got pretty high marks and didn’t have to buy a drink for an hour or so. All things must pass.

A few days after the incident, Sheila and I were sitting on our bar stools, drinking, when Maggie came down the bar to talk to us. You’d forgotten her, hadn’t you? I haven’t.

“I told Tommy your fish and chips story,” she said. I hadn’t forgotten him either.

“Uh, Maggie, what’s going on about the other day? Do I have to look over my shoulder?”

“Nah. Don’t worry about it. He’s fine. He wants to talk to you, though.”

“What about?”

“The fish and chips story.”

“What? Maggie, I—”

“No. Don’t worry! He just wants to hear the story. Do me a favor, talk to him. Okay?”

“Okay. When?”

“Tomorrow after work; just come in.”

“See you then.”

“I won’t be here.”

“Oh.”

Coming from the street into the bar always stopped me cold. My eyes, those shirkers, couldn’t adjust to the darkness quick enough. This would be the perfect time to get me. I couldn’t see a thing. Nothing happened. So far, so good. As my eyes adjusted, I moved to the bar to get a drink. First things first. He was sitting alone at the corner table, and after paying for my beer, I headed over.

“Maggie said you want to talk to me?” I didn’t think Clint Eastwood or even a crazy Jack Nicholson would work on this guy, so I said it like Steven Masterson. This was real.

“I do. Sit down.”

I did.

“Tell me the fish and chips story.”

Maybe this wasn’t real. I mean here I am, having a sit-down with a man known for his violence, whom I had publicly embarrassed just days earlier, and he wants me to tell him a story about Sheila and me going out for something to eat? But I know the story isn’t about fish and chips but about power and fear and hate, and this guy knows something about them. Maybe this is real. So I tell him about the fish and chips.

“That’s it?” he asked when I was done. “That’s the whole story?”

“Yes.”

“All right. Stop worrying about it. I have something to tell you. The other day when I was in here and that thing happened?”

“Yeah?”

“There were five or six other guys in here, and you were the only one to stand up.”

“Uh…well…”

“That’s the point. You stood up to protect Maggie. I respect that. Don’t you worry about that Spinnaker thing. I’ll take care of it. Be here tomorrow night. I have someone I want you to meet.” He stood up and walked out of the bar. I stood up too. I needed a drink.

“What was that all about?” they wanted to know at the bar.

“Fish and chips.”

“Bullshit. Are you still in trouble?”

“I may have gone from the frying pan into the fire. I don’t know.”

“Good luck, buddy.”

I sat on my stool and waited for Sheila. She always got there after me. Sometimes I was still sober. This was one of those times. I wanted a serious conversation. Well, maybe I wasn’t quite sober, but I wanted to talk anyway. “Steven,” she said, after our kiss, “what happened?”

“We’re going to jail.”

“No, we’re not; our records are almost clean. What about O’Rourke? What did he want?”

“He wanted me to tell him the fish and chips story.”

“You’re drunk already. Quit fooling around. What did he want?”

“No, I’m not. Well, maybe a little. But I’m not screwing around; that’s what he wanted.”

“You’re serious. What about the thing with Maggie? What about that?”

“That’s the thing. He tied them together. As strange as it seems, he thinks he owes me one for sticking up for Maggie. He said I was the only one who did, and he respected me for it. I guess this is some kind of strange thank-you or sign of respect. The thing at the Spinnaker, he said don’t worry about it. He would take care of it.”

“What the hell does that mean?”

“We’re going to jail. Sheila, you’ve heard the stories. I believe they could be almost true. If you had seen his eyes that first night, you would too. Intimidating a witness, jury tampering, or bribing a judge could lock us up for a long time. He wants me to meet someone tomorrow night.”

“Where?”

“Here.”

“I’m coming too.”

“Sheila, I don’t know how we can get out of this without getting in deeper. We’ve got to stay cool and think. Barkeep, two more beers!”

“No, make mine a Black Russian.”

The following day was long but not long enough. Sheila and I met outside the bar and went in together. First things first: we got a beer. He wasn’t there. Maggie was.

“Maggie, where’s Tommy?”

“He’ll be here in a minute and don’t worry.” She walked away.

I said, “Sheila, everybody keeps saying don’t worry, but we’re on a first-name basis with a hit man. It’s not very comforting.”

Speak of the devil and that damn sunlight poured through the door. It wasn’t Tommy. But he came in just behind a slightly plump woman. She was professionally dressed, wearing a pants suit and low heels. Sheila and I were expecting a big guy with a bent nose. We exchanged a “what’s this?” glance. I love looking into her eyes; sorry, that’s another story. Tommy motioned us to that same corner table.

“How are you guys doing?”

“Okay,” Sheila answered. “You?”

“This is my lawyer, Teresa Rossi. You tell her the story, and she’ll take care of it. Do what she says.” He turned and walked out of the bar. Teresa, Sheila, and I, in what was certainly an awkward and strange moment, pulled out chairs and sat down. I introduced Sheila and myself and didn’t know what else to say. Teresa did.

“I’m a criminal defense attorney,” she said. “I’m an associate at Bianca, Russo and Associates, a law firm in Boston. I’m going to help you.”

I was encouraged. She didn’t say “don’t worry.” I’d also heard of her firm. And I read the newspapers. At that time organized crime in New England was run from Providence by the ageing Raymond Patriarca. There was no shortage of Mafia trials. From the big man to loan sharks and soldiers to bagmen, this firm represented them all, even the mayor. They were going to represent me and Sheila?

“Tommy said you’d tell me the fish and chips story.”

I told her the story.

“This isn’t about fish and chips,” she said when I was finished.

“We know.”

“I can help you with this. I think you’ll walk away. When is the court date?”

“The eighteenth.”

“All right. Don’t do anything. I’ll call you on the seventeenth and tell you if we’re going. We may not go to court the eighteenth; we’ll see. I gotta go.”

Like that, she was gone.

Sheila and I were quiet, each of us thinking our own way through what had just happened.

Sheila broke the silence. “Steven, what do you think?”

“The law firm is big time. She’s a criminal defense lawyer in the best firm in Boston. We’re facing criminal charges. She comes with a good reference. What is our alternative?”

“Not a plea bargain. I don’t want assault charges on our records. We didn’t do anything and I won’t plead guilty to anything. We could hire another lawyer.”

“We have to remember Tommy. Not going with Teresa and hiring someone else could be disrespecting him. I don’t know. Anyway, who would we hire that we know would be better?”

“So we do it?”

“I think so.”

“Okay.”

“Let’s have a shot and a beer.”

“Make mine a Black Russian.”

As the court date got closer, our anxiety increased. Finally, on the seventeenth, Teresa called. “Stay home tomorrow. I’ll call with the new court date.” Three weeks later she called. “The court date is tomorrow. Stay home.” I was beginning to see a pattern. We were judge-shopping. Not buying. Shopping. I hoped. Two days later the phone rang. “The date is the sixteenth. Be there.” She must have gotten the right one.

On the sixteenth we were there, standing outside the courthouse, waiting for Teresa. She didn’t show. The only time we had spoken to her was when she had given us the date. Maybe she had forgotten to call us when she wanted another “no show.” Maybe she had gotten here before us and was inside?

“Steven, it’s nine o’clock. We’d better get in there and see what’s up. If we’re on for today, we’d better make first call.” We climbed up the stone stairs and into the building. Very impressive. The police station and courthouse were in the same building. Very oppressive. There isn’t much room for the separation of powers.

We found the courtroom and went in; court hadn’t started yet. We stood inside and searched with our eyes, even my traitorous ones. No one involved with our case was there.

“Sheila,” I asked, “do you see anyone?”

“No, just that bailiff staring at us and headed this way. I don’t think it’s good, but his hand isn’t on his gun.”

He approached us. “Miss Lyons? Mr. Masterson?”

“Yes.”

“Yes.”

“Would you come with me, please? They’re all in the judge’s chambers. I was asked to bring you in as soon as you arrived.”

Sheila and I exchanged that “what’s this?” glance and followed him to the judge’s chamber, the holiest of holies, and we were being escorted there. I bet it had been a while since a defendant had been in there. When we were inside and the door closed, we stood there. Everybody had a chair but us. The bouncer was there; so was the guy who sucker-punched me. The judge was there and so was Teresa. The guy who owned the Spinnaker sulked in the corner. The bouncer and his pal didn’t look too happy either. There was another guy in the room, the prosecutor, I guessed. He had a chair too. Everybody had a chair but us. We wouldn’t need them.

Teresa spoke up. “Your Honor, this is Miss Lyons and Mr. Masterson, the defendants in this case.”

“Okay,” the judge said, looking at us, “here’s the deal.”

I didn’t like the sound of that. Sheila touched my hand to tell me she didn’t either.

“Your attorney came to court today ready to go to trial,” continued the judge. “She discussed your case with the prosecutor. She also offered him an alternative, a document prepared by her in which you agree not to sue the city or its employees.” We looked at Teresa, who slightly nodded her head. Ours turned back to the judge.

“For their part, the city will drop all charges. The prosecutor here has agreed and signed for the city. All you have to do is sign. Do you both understand this? Do you understand you will be giving up some of your rights?”

Sheila and I looked at each other. Of course we did. I may not look it but Sheila is pretty smart. Getting a head nod from Teresa, we knew what to do.

“Yes, Your Honor, I understand,” I said.

“Yes, Your Honor, I understand,” repeated Sheila.

“Would either of you like to speak to your attorney?”

“No, Your Honor, I’m ready to sign,” Sheila spoke first, making me repeat.

“No, Your Honor, I’m ready to sign.”

Just like that we had surrendered our God-given right to sue the City of Pawtucket. We, or I should say Teresa, had also solved our problem. Assaulting a police officer had gone away without a plea bargain. Well, I guess that’s not technically true; we couldn’t sue the bastards. But still it was a good day.

Once we had signed, the judge said it was over and closed the case. All the guys in chairs beat us out of chambers. We waited for Teresa while the cop ran like he was being chased by a suspect. With a nod [boy, she’s good at that], Teresa ushered us toward the door; she passed in front of me, and I was the last man out. I didn’t make it.

“Mr. Masterson,” I heard the judge say.

“Yes, Your Honor?”

“You had a good lawyer here today.”

“Thank you, sir. We think so too.”

I went through the door and hustled to catch up to Sheila and the genius attorney. They were being badgered by the Spinnaker owner: “I was left out of the deal! You have to sign a release for me!” I caught up and Teresa asked us if we wanted to sue the guy. We didn’t.

“I was left out of the deal! You have to sign a release for me!”

“No,” Teresa said to him. “Let him worry about it,” she said to us.

And then we were out of the courthouse and moving down the street. I began to feel cleaner. We put some distance between us and it and stopped. Sheila and I profusely thanked our attorney. We had been in a jam and we knew it. Teresa had beaten them and we knew that too. There were some things we didn’t know.

“What the hell just happened in there? They were afraid of us? We had to sign off on lawsuits? What just happened?” It was Sheila asking the questions.

“They were afraid of our witnesses,” Teresa answered.

“We didn’t have any,” I said.

“They didn’t know that.”

“Teresa, you hot ticket,” laughed Sheila.

I knew I didn’t want to play poker with the woman. “Teresa, thank you again,” I said.

“Yes, thank you,” said Sheila. “How much do we owe you?”

“Nothing, Tommy’s taking care of it. Don’t worry.” With a nod of her head, she was gone. We would never see her again.

“Sheila, she said it right there at the end. Don’t worry. I’m worried.”

“Knock it off, Steven. It’s over. Stop worrying.”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right. It’s over.”

“Okay, what do you want to do now? We’ve got the day off.”

“It’s Friday. How about fish and chips?”

“Jerk.”

“How about a shot and a beer?”

“Make mine a Black Russian.”

A year or two later, the Spinnaker Lounge closed down. It never reopened. Maybe too many unsigned releases? I don’t know.

Maggie left the bar business and started her own construction firm. I hope she was successful.

Teresa Rossi lost her law license and went to jail on drug and weapons charges. I hope she is now doing well.

Tommy O’Rourke, found guilty on other federal charges, was also determined to be a “dangerous special offender” under federal law. And I was worried. Sheila and I went to his going-away party. He’d be gone a long time. To him I say thanks.

A year or two later, Sheila and I quit drinking. We haven’t had a drink in twenty-nine years. Haven’t been arrested either. For over thirty years we have been lovers and partners, husband and wife. We still like our fish and chips.