| <- Back to main page |

“Oh, he had a way with a yarn, did Mr. Irving,” Bing Crosby croons in The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. The 1949 Disney film with its romping, shiver-worthy finale introduced the Headless Horseman to 20th century kids and fanned the embers of Washington Irving’s gently cooling reputation. He remains just on the periphery of literary consciousness, thanks to “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and another fantastical yarn, “Rip Van Winkle”. Rip, like Ichabod Crane and the Hessian specter, has entered the pantheon of fairy tale characters—though Irving never set out to write for children. While his creations continue to roam freely down the passages of popular culture—from “Nearly Headless Nick” in the Harry Potter books to a headless phantom in an episode of Scooby Doo—the man himself remains an obscure American storyteller of the Romantic era, a scribbler of tales who never produced a novel and whose sketches and mock-histories are as quaint and out of date as the old Dutch Manhattanites he wrote about.

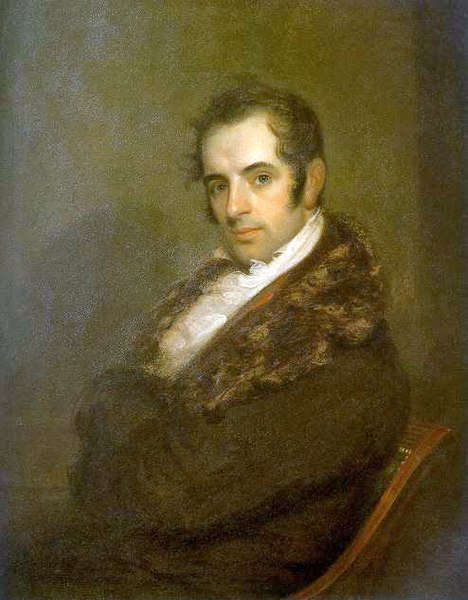

But Washington Irving lived a life that was almost as fantastical as his tales. He was blessed by George Washington and hosted by Sir Walter Scott; he was published by Murray, hung out with Thomas Moore and Prince Frederick of Saxony, and visited Aaron Burr in his prison cell; he gate-crashed a White House ball and encountered pirates; he romanced Mary Shelly and made Byron weep; he saw the ships departing for Trafalgar and helped save the Alhambra; he inspired Dickens and Longfellow, provided Clement Moore with his depiction of Santa Claus, and nicknamed New York City “Gotham” over a century before the first Batman comic; he suffered from a tragic romance and remained a confirmed bachelor; living much of his life abroad, he was the first American writer to reach an international audience—yet remained a quintessentially New York writer. His infancy coincided with his country’s; he was our myth-maker, and much of the rest of American literature was built on the foundations he laid in the wilderness of the new nation. As Irving scholar Peter Norberg notes, “Three generations after the Revolutionary War, George Washington was revered as the father of our country. Irving likewise was recognized as a founding father of America’s national literature.”

The famous meeting with George Washington occurred in 1789, when Irving was a boy of six. In New York following his inauguration, the first president of the United States was recognized in a shop by Irving’s Scottish nurse, Lizzie. Washington (the boy), who was born the same week in April 1783 that the cease-fire ending the Revolutionary War was announced, was introduced to his namesake, and Washington (the man) blessed him. President Washington could not have guessed that the child standing before him would grow up to have quite as eventful a life as his own, and become a famous writer whose last major work would be the five-volume biography The Life of George Washington, published seventy years later. The Washington Irving of 1789 was a dreamy kid from a fairly prosperous New York merchant family, the youngest of eight children of an Orkney Islands seaman who had been a petty officer in the Royal Navy. Young Washington was already showing a predilection for wandering and adventure. As Irving would later write in the introduction to The Sketch Book:

Even when a mere child I began my travels, and made many tours of discovery into foreign parts and unknown regions of my native city, to the frequent alarm of my parents and the emolument of the town crier.

As an adolescent, Irving expanded his voyages to include neighboring villages, like Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow, and later up the Hudson to the Catskill Mountains, where he hunted deer and met Native Americans. He was also an avid reader of adventure tales, including English novels such as Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe. He attended a strict school run by a Revolutionary War veteran, but was an indifferent student, often sneaking out the window and over the rooftops in the evening to stroll the wharves or visit the theater.

As the baby of the family, Washington was not expected to take over the merchant business. Instead, Irving clerked at a law office starting in 1799, later working for Judge Josiah Hoffman. His older siblings were a strong influence, and his first published writings were letters in the Morning Chronicle, edited by his brother Peter. Written under the pseudonym of “Jonathan Oldstyle”, they contain satirical commentary on the latest fashions, ballroom manners, wedding customs, and the like. Though he was only nineteen years old, Irving’s writing already bears the stamp that would mark his more famous later pseudonyms, Diedrich Knickerbocker and Geoffrey Crayon. In imitating the crankiness of an old man, he cannot quite disguise the nostalgia of romantic youth:

The customs that prevailed in our youth become dear to us as we advance in years; and we can no more bear to see them abolished than we can to behold the trees cut down under which we have sported in the happy days of infancy [...] I often sigh when I draw a comparison between the present and the past; and though I cannot but be sensible that, in general, times are altered for the better, yet there is something, even in the imperfections of the manners which prevailed in my youthful days, that is inexpressibly endearing.

Irving broadened his travels in 1804, when his brothers Peter and Ebenezer, fearing he was becoming consumptive, sent him on a trip to Europe. He traveled through France and Italy, meeting Madame de Staël and the American painter Washington Allston, and saw the British fleet sailing through the Strait of Messina. His own ship was robbed by pirates while en route to Sicily, but Irving managed to hide his money in time.

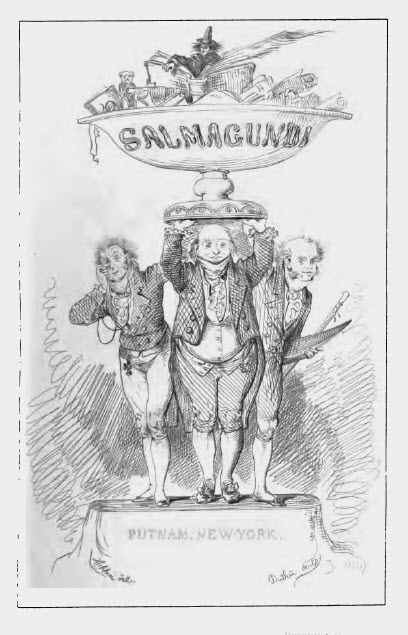

On returning to New York, Irving once more took up the law, though he had little zeal for it. “I could study any thing else rather than law,” he later wrote, “and had a fatal propensity to belles-lettres.” Still, he managed to pass the bar in 1806. He also fell in love—with fifteen-year-old Matilda Hoffman, the daughter of his employer. “Her mind seemed to unfold itself leaf by leaf, and every time to discover new sweetness,” he would later recount. It was during this period that Irving became a “gay young blade” and one of “the lads of Kilkenny,” a social and literary club of which his brothers William, Peter and Ebenezer were also members, along with his good friend Henry Brevoort and James Paulding. It was with William and Paulding that he co-authored his first important literary work, the journal Salmagundi. The three published twenty issues, mostly in 1807, filled with tongue-in-cheek commentary and parodies of the manners and prominent personages of their native city, “the thrice renowned and delectable city of Gotham” (literally “goat’s town” in Anglo-Saxon). The publishers kept their identities secret, and articles were from outrageously-named characters like Launcelot Longstaff and Mustapha Rub-a-Dub Keli Khan. The overall attitude was one of insouciance and irreverence:

We are critics, amateurs, dilettanti, and cognoscenti; and as we know “by the pricking of our thumbs,” that every opinion which we may advance in either of those characters will be correct, we are determined though it may be questioned, contradicted, or even controverted, yet it shall never be revoked.

It was also in 1807 that he met Aaron Burr, after being hired on retainer by a mutual friend to write about him during his trial for treason in Richmond. Irving wrote nothing in public, though in a private letter he confided, “...I consider him as a man so fallen, so shorn of the power to do national injury, that I feel no sensation remaining but compassion for him.” In the end, he didn’t need to: Burr was found innocent due to lack of evidence, despite all President Jefferson’s efforts to convict him.

Irving’s next literary escapade was A History of New York. Begun as a parody of a well known travel book, Samuel L. Mitchill’s The Picture of New York, Irving’s free-wheeling, legend-laden account of Dutch Manhattan had by the time of its publication in 1809 turned into something more earnest and sincere. As he explains in his introduction to the 1848 edition, “… I was surprised to find how few of my fellow-citizens were aware that New York had ever been called New Amsterdam, or had heard of the names of its early Dutch governors, or cared a straw about their ancient Dutch progenitors.” One fascinating aspect of the volume is its connection with Santa Claus. Irving describes how Oloffe the Dreamer (Oloff Van Cortlandt, the founder of Manhattan) was guided by a vision of St. Nicholas, smoking his pipe “and laying his finger beside his nose,” to indicate the spot where the new community should be founded. Later he adds:

… so we are told, in the sylvan days of New Amsterdam, the good St. Nicholas would often make his appearance in his beloved city, of a holiday afternoon, riding jollily among the treetops, or over the roofs of houses, now and then drawing forth magnificent presents from his breeches pockets, and dropping them down the chimneys of his favorites.

In 1823 Clement Clarke Moore, who most people credit for authoring “A Visit from St. Nicholas”, based his St. Nicholas on the image sketched by his friend Washington Irving in A History of New York. We have not only Irving’s flying sleigh, but also the pipe:

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke, it encircled his head like a wreath;

And also the finger by the nose as a sign:

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

Irving published A History of New York under the nom de plume of Diedrich Knickerbocker, who is described as “a small elderly gentleman, dressed in an old black coat and cocked hat.” In a brilliant marketing scam that was a century or so ahead of its time, the author had a notice printed in the Evening Post about the disappearance of one Knickerbocker, seeking help finding him as “there are some reasons for believing he is not entirely in his right mind...” A few weeks later, another notice appeared, this one from his landlord, Seth Handaside, saying that Mr. Diedrich Knickerbocker was still missing, and further, that “a very curious kind of a written book has been found in his room, in his own handwriting.” If Mr. Knickerbocker did not appear to discharge his bill for rent and board, Mr. Handaside would be forced to publish the book to pay off the debt. Another notice gave the book’s title, and few weeks later, the town’s curiosity being duly stoked, A History of New York itself appeared in stores as if by magic, having been secretly printed in Philadelphia.

The stunt paid off—local authorities were so taken in by the Knickerbocker story that they offered a reward for his safe return. Meanwhile the historical parody of old New Amsterdam flew off the shelves, and Irving, whose authorship was soon after revealed, became a literary celebrity. But already the days of his rollicking youth had ended. In the spring of 1809 his fiance Matilda Hoffman had died of tuberculosis, leaving Irving grief-stricken. In a note written later, and found after his death with a miniature of Matilda, Irving recounts this dark time:

I cannot tell you what I suffered. The ills that I have undergone in this life, have been dealt out to me drop by drop, and I have tasted all their bitterness. I saw her fade rapidly away; beautiful and more beautiful, and more angelical to the very last [...] I cannot tell you what a horrid state of mind I was in for a long time—I seemed to care for nothing—the world was a blank to me—I abandoned all thoughts of the Law—I went into the country, but could not bear solitude yet could not enjoy society—There was a dismal horror continually in my mind that made me fear to be alone—I had often to get up in the night & seek the bedroom of my brother, as if having a human being by me would relieve me from the frightful gloom of my own thoughts.

Months elapsed before my mind would resume any tone; but the despondency I had suffered for a long time in the course of this attachment, and the anguish that attended its catastrophe, seemed to give a turn to my whole character, and throw some clouds into my disposition, which have ever since hung about it.

Though many warm friendships and even a few romances attended him in later years, Irving would remain a life-long bachelor.

Had his life and career progressed as he imagined it, it is doubtful whether we would be reading Washington Irving at all in the 21st century, or indeed that his literary reputation as a writer of fashionable wit and humor would have lasted more than a decade or two. What, if anything, he would have written after A History of New York had Irving remained comfortably ensconced at the New York bar is unknowable, but it’s certain that The Sketch Book and his other masterpiece, Bracebridge Hall, would never have come into existence had not Irving found himself an impecunious American in England, falling back on his pen to earn a living.

There is almost a decade between the publication of A History of New York and The Sketch Book, during which Irving joined a new import business founded by his brothers Peter and Ebenezer, P & E Irving, took a job editing a Philadelphia journal called Analectic Magazine (and found he had no tasted for editing), visited Washington and showed up uninvited at a ball at the White House (but was well received by Dolly Madison and introduced to her husband James), became aide-de-camp to New York’s governor, Daniel Tompkins, during the War of 1812 (but saw no action), and did very little original writing.

In the momentous year of 1815, Irving’s life took a fateful turn. With the War of 1812 concluded in a peace treaty, Irving took the opportunity to return to England, both for pleasure and to assist his brother Peter, who was working the English side of the import business from Liverpool. He arrived in time to witness the celebrations in London following the Battle of Waterloo, but his plans for another tour of the continent were put on hold due to Peter’s rheumatism and other health issues. It turned out that the business was in a bad state, due to lack of demand for English goods in America in the aftermath of the war, and Peter’s over-purchasing. Irving borrowed from friends to pay the firm’s debts, but bankruptcy was inevitable. To relieve the gloom of his situation, he took lodgings near Westminster in London in 1817, and, thinking to write his way out of debt, began what would be his most memorable work, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. He also spent time with his sister Sarah Van Wart in Birmingham, and renewed friendships with Allston and Charles Leslie. He made new friends too, paying calls on Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Sir Walter Scott, who had been given a copy of A History of New York by Irving’s friend Brevoort, and liked it. It was Scott who, more than anyone, influenced Irving’s later writing career. Staying at Scott’s home of Abbotsford for a few days, the young American imbibed his host’s interest in legends and folklore, and Sir Walter inspired him to compose his own Gothic tales.

His brother William, now a Representative in Congress, was able to secure a lucrative position as first clerk in the Navy Department back in Washington for him—but Irving turned the offer down. Nothing could now dissuade him from his work. As he explains to his brother Ebenezer in an 1819 letter:

I require much leisure and a mind entirely abstracted from other cares and occupations, if I would write much or write well.

I have been for some time past nursing my mind up for literary operations, and collecting materials for the purpose.

I feel myself completely committed in literary reputation by what I have already written; and I feel by no means satisfied to rest my reputation on my preceding writings. I have suffered several precious years of youth and lively imagination to pass by unimproved, and it behooves me to make the most of what is left. If I indeed have the means within me of establishing a legitimate literary reputation, this is the very period of life most auspicious for it, and I am resolved to devote a few years exclusively to the attempt.

Irving sent the sketches in packets to Brevoort in America, and The Sketch Book was published in seven installments by C.S. Van Winkle in New York. The work received glowing reviews, and some of the sketches wound up being published in British newspapers. Irving did not believe his commonplace portraits of the English would be of interest in England itself, but when a London book seller was preparing an unauthorized edition, he set to work finding a British publisher. With Scott’s help he managed to land John Murray, the publisher of Lord Byron, Jane Austin, and Scott himself. A two-volume hardcover edition of The Sketch Book appeared in London in 1820.

Nothing even remotely like it is being published today, or has been in the past century, to my knowledge. Such a work would be like a mash-up of Paul Theroux’s travel writing, Bill Bryson’s nonfiction, Stephen King’s short stories and Billy Collins’ poetry. In Irving’s day, before photography, young Americans on the “Grand Tour” of Europe would take a sketch pad along and make drawings of places like the Colosseum or Notre Dame. Irving’s book was the literary equivalent of this, though he confined his sketches for the most part to England. Unlike his previous writing personas, Geoffrey Crayon is pretty much Irving himself. His rambling collection of character and place descriptions, stories, anecdotes and ruminations have chapter titles like “Rural Life in England” and “The Boar’s Head Tavern, Eastcheap”. “The Mutability of Literature” finds Crayon ensconced in the library of Westminster Abbey, where, in a quirky turn of Romantic surrealism, the little quarto he has taken to read suddenly begins speaking to him:

“Sir,” said the little tome, ruffling his leaves and looking big, “I was written for all the world, not for the bookworms of an abbey. I was intended to circulate from hand to hand, like other great contemporary works, but I have been clasped up for more than two centuries, and might have silently fallen a prey to these worms that are playing the very vengeance with my intestines if you had not by chance given me an opportunity of uttering a few last words before I go to pieces.”

Crayon philosophizes with the book, explaining that most of its contemporaries have long since passed away, and most of the great authors of its age have likewise fallen into obscurity.

The longing for past days and obsolete customs can also be found in the series of sketches about Christmas at an old manor house called Bracebridge Hall—“The Stagecoach”, “Christmas Eve”, “Christmas Day”, and “The Christmas Dinner”. Goeffrey Crayon, a foreigner traveling alone in a stagecoach on Christmas Eve, happens to meet his old friend Frank Bracebridge, who invites him to his family’s estate for the holiday. At Bracebridge Hall, “an irregular building of some magnitude,” he meets “the old squire,” Frank’s father, who keeps Christmas up according to the old rural traditions. In the great hall there is a family supper followed by dancing to a harpist. There is also licensed merriment in the servants’ hall:

Here were kept up the old games of hoodman blind, shoe the wild mare, hot cockles, steal the white loaf, bob apple, and snap dragon; the Yule log and Christmas candle were regularly burned, and the mistletoe, with its white berries, hung up to the imminent peril of all the pretty housemaids.

That Irving had to add a note explaining the custom of the mistletoe, along with caroling and the Wassail Bowl, shows how out of usage such Christmas traditions were in the early 19th century. Along with his portrait of St. Nick, Irving’s Christmas sketches helped revive the holiday in America, and were one of the inspirations for Charles Dickens to write his classic A Christmas Carol some twenty years later.

“The Inn Kitchen” introduces one of Irving’s favorite devices—a traveler’s sketch (in this case of an inn in The Netherlands) that depicts people telling stories, allowing him to politely introduce a good old yarn. It is as if Irving, gentleman of the world, were himself too respectable and high-minded for such tales, but is only including the story by way of a childish artifact. In this case the tale he relates is “The Specter Bridegroom”, a supernatural satire that turns on the folk belief, common throughout northern Europe, that if an affianced lover dies before the actual wedding, they will make a ghostly visitation to their intended. Irving’s talent for romantic portraiture is on display as the bride-to-be, the Baron Von Landshort’s daughter, awaits for the arrival of a future husband that she has never met:

The suffusions that mantled her face and neck, the gentle heaving of the bosom, the eye now and then lost in reverie, all betrayed the soft tumult that was going on in her little heart.

The two most famous stories in The Sketch Book, however, are slipped in without a framework. Both are set in America, and said to be found among the papers of Irving’s old persona, Diedrich Knickerbocker.

“Rip Van Winkle” is a fairy tale written for adults. It tells the story of an easygoing but incompetent farmer with a termagant wife who wanders off squirrel hunting and, after meeting a band of fairies in the Catskill mountains playing ninepins, drinks some of their “Hollands” gin and falls asleep for twenty years. The premise of an enchanted sleep is not, of course, original—“Sleeping Beauty” is another example. Irving probably based his famous tale on the German folk tale “Peter Claus”, about a goatherd who has a similar experience when searching in the woods for a lost goat. In “Rip Van Winkle”, though, he dresses up the story in American clothes. The setting is among the Dutch colonists in New York, and the fairies are identified as Henry Hudson and his crew, who make a noise of thunder with their bowling. Irving’s naturalistic descriptions of the rugged Catskills are not unlike the romantic paintings of the American wilderness by artists such as Thomas Cole. He has Rip pause for rest on a high green knoll and admire the scene:

From an opening between the trees he could overlook all the lower country for many a mile of rich woodland. He saw at a distance the lordly Hudson, far, far below him, moving on its silent but majestic course, with the reflection of a purple cloud, or the sail of a lagging bark, here and there sleeping on its glassy bosom, and at last losing itself in the blue highlands.

And Irving uses the twenty year sleep to provide a happy ending for his hero: Rip returns to his village to find his wife dead, and the portrait of King George at the inn replaced with George Washington. His daughter welcomes him to live with her and her “stout cheery farmer” husband in their “snug, well-furnished house,” where he can spend the remainder of his days in the delightful idleness of old age. Rip also manages to blissfully sleep through the tumultuous period of the American Revolution, and this is a powerful part of the spell woven by the story. As Peter Norberg points out:

Irving grew up in a post-Revolutionary America torn between its democratic aspirations for the future and its memories of the colonial era. During his boyhood, British sympathizers lived next door to veterans of the Continental army. Memories of the hardships endured while quartering British troops during the occupation of New York were mixed with frustration over financial losses incurred from the severing of ties with Great Britain. The War of 1812, often referred to as the Second War of American Independence, rekindled and put to rest some of these memories, but the early republic continued to be haunted by its British colonial past. The story “Rip Van Winkle” wonderfully illustrates Irving’s strategy for putting these ghosts to rest.

Part of that “strategy” had to do with the way Irving managed to shift America’s origin story. Just as in A History of New York, it is the early Dutch colonists of New Netherland who are the focus, not the English colony of New York that followed. And he uses this same background in the other American tale from The Sketch Book, which is probably his best known story, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”:

From the listless repose of the place, and the peculiar character of its inhabitants, who are descendants from the original Dutch settlers, this sequestered glen has long been known by the name of SLEEPY HOLLOW, and its rustic lads are called the Sleepy Hollow Boys throughout all the neighboring country. A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and pervade the very atmosphere.

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is a short masterpiece of Romantic fiction; it fits the pattern that Scott first designed with Waverly, that was followed by Balzac, Mérimée, Cooper, and other Romantic writers down to Emily Brontë and Bram Stoker: an everyman hero from “civilization” (Ichabod Crane) infiltrates an exotic and “primitive” society (an isolated Dutch community), falls in love with a femme fatale among the natives (Katrina Van Tassel), and becomes caught up in its struggles and superstitions (the legend of the headless horseman). In this case the Romanticism is in a humorous vein, as Irving makes it clear that the appearance of the headless specter, which frightens Ichabod out of town, was got up by Brom Bones, the head of the Sleepy Hollow Boys and his rival for Katrina’s hand. It is, then, a mock-ghost story, rather than a mock-epic. It is also, like “Rip Van Winkle”, a story sunk in the healing shadows of a dream. We are told that the rider is “the ghost of a Hessian trooper, whose head had been carried away by a cannon-ball, in some nameless battle during the revolutionary war.” By laughing off the story, Irving dismisses from the reader’s mind the haunted memory of America’s violent birth.

Headless riders, like charmed sleep, often appear in European folklore—for example the Dullahan in Ireland and the Green Knight in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Irving’s famous legend, however, may have been set in Sleepy Hollow because the headless corpse of a Hessian Jäger was actually found there after a skirmish in 1776. The Van Tassel family (a real family, on whose daughter Irving based his character Katrina Van Tassel) had it buried in an unmarked grave in the Old Dutch Burying Ground there. Ichabod Crane was also real—he was an army captain Irving met when inspecting fortifications in 1814—though his character was probably based on a school master Irving met at nearby Kinderhook. And so it is from such ordinary clothes that legends are woven.

Although the Gothic stories in The Sketch Book are more remembered today, and often singled out for anthologies and compilations, Irving’s compassionate, humanistic side shines more brightly from the essays and incidental pieces. “The Broken Heart”, a melancholy meditation on the sweetheart of an Irish patriot executed for treason, is all kindness and sympathy. “There are some strokes of calamity,” he writes, “which scathe and scorch the soul—which penetrate to the vital seat of happiness and blast it, never again to put forth bud or blossom.” And in “Traits of Indian Character”, an essay written for the Analectic Magazine and stuck into the English edition to flesh out the American authorship of the book, he begins the long process of breaking old stereotypes and prejudices against Native Americans:

It has been the lot of the unfortunate aborigines of America, in the early periods of colonization, to be doubly wronged by the white men. They have been dispossessed of their hereditary possessions by mercenary and frequently wanton warfare, and their characters have been traduced by bigoted and interested writers. The colonist often treated them like beasts of the forest, and the author has endeavored to justify him in his outrages. The former found it easier to exterminate than to civilize, the latter to vilify than to discriminate.

For being such a grab bag of story, opinion and anecdote, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. sold remarkably well on both sides of the Atlantic. The British were astonished to find that there was actually an American writer who could compare with Addison or Goldsmith, though William Hazlitt complained, rather snobbishly, that “he gives us very good American copies of our British Essayists and Novelists, which may be very well on the other side of the water, or as proofs of the capabilities of the national genius, but which might be dispensed with here, where we have to boast of the originals.” But many English reviewers were enchanted with Irving, as well as Romantic writers such as Scott and Byron, who claimed “The Broken Heart” moved him to tears. "I am astonished at the success of my writings in England," Irving wrote to Murray, "and can hardly persuade myself that it is not all a dream. Had any one told me a few years since in America, that any thing I could write would interest such men as [...] Byron, I should have as readily believed a fairy tale."

On the American side, where readers still remembered him as the author of A History of New York, sales were also brisk. Longfellow, who at the time the book was published was a lad of around twelve, later wrote: “Every reader has his first book; I mean to say, one book among all others which in early youth first fascinates his imagination, and at once excites and satisfies the desires of his mind... To me, this first book was The Sketch Book of Washington Irving.”

The runaway success of The Sketch Book gave Washington Irving financial independence and no little celebrity. He had proved to his family that he could support himself in that most singular career, as an American man of letters, and he chose to stay in England, as it provided much fodder for his pen. He began frequenting dinners and galas, met Robert Southey, John Jacob Astor and the Duke of Wellington, and in Paris befriended the Irish poet Thomas Moore.

He also continued writing at a good clip, working on sketches for Bracebridge Hall (published in 1822). Like a band with a #1 record who quickly heads back to the studio to record something similar, Bracebridge Hall is written along the same lines as, and is a sort of sequel to, The Sketch Book. Irving uses the same persona, Geoffrey Crayon, who now has returned to the site of his Christmas sketches as a guest at the wedding of the old squire’s son Guy (the dashing army captain) and his ward, the fair Julia. Subtitled “The Humorists” and dubbed “A Medley”, most of Irving’s formula remains the same: sketches of English life, including vignettes of local personalities and pastimes such as falconry and fortune telling. And of course, stories. The change here is that Irving has narrowed his scope to one ancestral hall and its surrounding village and countryside. This actually makes the volume as a whole more polished and harmonious, and builds narrative tension up to the day of the wedding. In fact, I consider Bracebridge Hall to be Washington Irving’s underappreciated masterpiece.

Often addressing his audience in the first person present, as though writing a journal entry, Irving seems at once fresher and more mature. In his introductory “The Author”, he’s at his genial best:

I have always had an opinion that much good might be done by keeping mankind in good-humour with one another. I may be wrong in my philosophy, but I shall continue to practise it until convinced of its fallacy. When I discover the world to be all that it has been represented by sneering cynics and whining poets, I will turn to and abuse it also; in the meanwhile, worthy reader, I hope you will not think lightly of me, because I cannot believe this to be so very bad a world as it is represented.

Bracebridge Hall itself is probably modeled on Aston Hall, a bucolic estate within walking distance of the Van Wart’s home in Birmingham. The whimsical characters he peoples it with might be compared to Chaucer’s pilgrims—every class of society is represented, from publicans to school masters to the old squire’s rich relative, Lady Lillycraft, and his old factotum, Master Simon. But there is also plenty of time for Irving to stroll about and philosophize. In “Family Reliques” he haunts the picture gallery, contemplating portraits of great men and beautiful ladies long since passed away:

I was gazing, in a musing mood, this very morning, at the portrait of the lady, whose husband was killed abroad, when the fair Julia entered the gallery, leaning on the arm of the captain. The sun shone through the row of windows on her as she passed along, and she seemed to beam out each time into brightness, and relapse in to shade, until the door at the bottom of the gallery closed after her. I felt a sadness of heart at the idea, that this was an emblem of her lot: a few more years of sunshine and shade, and all this life, and loveliness, and enjoyment, will have ceased […] like myself, when I and my scribblings shall have lived through our brief existence and been forgotten.

There is plenty of good humor to go around as well. One of the frequent targets of Irving’s wit is the squire’s penchant for reviving old traditions and eschewing anything modern. “Among the other evils which have followed in the train of the fatal invention of gunpowder, the squire classes the total decline of the noble art of falconry,” we learn in “Falconry”, and in the companion sketch, “Hawking”, the entire household assembles to watch a Welsh falcon flying under the management of old Christy, the head huntsman of the estate. The bird is released after a flock of crows, but misses her target:

...The hawk, disappointed of her blow, soared up again into the air, and appeared to be “raking” off. It was in vain old Christy called, and whistled, and endeavored to lure her down; she paid no regard to him: and, indeed, his calls were drowned in the shouts and yelps of the army of militia that had followed him into the field.

At this point Julia, intent on watching the falcon, rides too near the stream and is thrown off her horse, causing everyone to forget about the falcon, who is never seen again.

Although the stories in Bracebridge Hall are not as iconic as “Rip Van Winkle” or “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, they are very good, and have the added charm of being entirely novel to the reader. Each is set naturally within the framework of the book. “The Stout Gentleman”, a rather neurotic tale about a mysterious occupant at an inn who is overheard but never seen, is told over supper by a narrator who “was a thin, pale, weazen-faced man, extremely nervous, that had sat at one corner of the table, shrunk up, as it were, into himself, and almost swallowed up in the cape of his coat, as a turtle in its shell.” The darker “The Student of Salamanca”, set in Spain and dealing with alchemy and forbidden love, is read by the captain in the library to amuse the recovering Julia; it is a manuscript, he tells us, written by a fellow soldier. And Lady Lillycraft furnishes us with “Annette Delabre” as the guests assemble in the sitting room on a May morning. The melodramatic tale of a disturbed young French woman whose lover, thought dead, suddenly reappears in the village, was written, she tells us, by the parson of her old parish. The most ambitious tale, however, is provided by Geoffrey Crayon himself.

In “The Historian” he is asked to tell a story around the dinner table; Crayon reads a manuscript from our old friend Diedrich Knickerbocker—one Irving persona quoting another—that begins with “The Haunted House”. The dwelling in question is in Manhattan, and was built during the Dutch colonial period. Knickerbocker remembers it from his boyhood:

Part of the roof of the old house had fallen in, the windows were shattered, the panels of the doors broken, and mended with rough boards, and there were two rusty weathercocks at the ends of the house which made a great jingling and whistling as they whirled about, but always pointed wrong. The appearance of the whole place was forlorn and desolate at the best of times; but, in unruly weather, the howling of the wind about the crazy old mansion, the screeching of the weathercocks, the slamming and banging of a few loose window-shutters, had altogether so wild and dreary an effect, that the neighborhood stood perfectly in awe of the place, and pronounced it the rendezvous of hobgoblins.

In the next story in the cycle, “Dolph Heyliger”, Knickerbocker relates a story he heard told about the house by “an old gentleman of the neighborhood,” John Josse Vandermoere. The title character is a medical student who is asked to stay in the house by his employer, Dr. Knipperhausen, who has bought it as a retirement home and wants to disprove the local rumors that it is haunted. Dolph’s subsequent adventures make up one of the most imaginative ghost stories ever committed to the page. Free from the cultural associations that have accumulated around his more famous stories, “Dolph Heyliger” brings us face to face with Irving’s visionary power and knack for the uncanny.

By-and-by he thought he heard a sound as if some one was walking below stairs. He listened, and distinctly heard a step on the great staircase. It approached solemnly and slowly, tramp—tramp—tramp! It was evidently the tread of some heavy personage; and yet how could he have got into the house without making a noise?

At one point Dolph himself is the rapt audience for a tale told by Anthony Vander Heyden, a merchant from Albany, called “The Storm-Ship”, which, like “Rip Van Winkle”, involves a legend about Henry Hudson and his crew. So now there are four levels of nested stories, giving the reader a fun house mirror sort of disorientation—like the early 19th century equivalent of a Jorge Luis Borges story.

Bracebridge Hall cemented Irving’s reputation as the first American man of letters, and he became a minor celebrity in Europe. Visiting the spas of Holland and Germany for his health, he made an extended stay on the Continent, dazzling the court of the King of Saxony in Dresden and becoming friends with the Prince Frederick (later King Frederick Augustus II). It was also here that he met Mrs. Amelia Foster, an American mother of five, and became enchanted by her 18-year-old daughter Emily. Emily Foster describes him in her journal as being “neither tall nor slight, but most interesting, dark, hair of a man of genius waving, silky, and black, grey eyes full of varying feeling, and an amiable smile.” All this could not, however, win her heart it seems, as she refused Irving’s offer of marriage in 1823. He might have had more success with Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who he met in London the next year. She had just returned to London following Percy’s death by drowning in Italy, and was introduced to Irving by John Howard Payne, an actor with whom he had collaborated on some plays. Payne himself had courted the young widow, but when Mary refused him, he steered Irving towards her. Though the whole thing sounds like it came from a Regency Romance plot, it didn’t work: Washington didn’t take the bait, and though Mary seemed to fancy him, nothing came of their relationship.

1824 also saw the publication of Tales of a Traveler, Irving’s last major collection of fiction. Written again under the aegis of Geoffrey Crayon, it nonetheless lacks much of the personal, idiosyncratic touches that charmed readers of The Sketch Book and Bracebridge Hall. This is a slicker, more commercial volume, mostly of stories Irving had collected on his travels through Europe. The frameworks are perfunctory: ghost stories told during an English hunting dinner, tales of banditti swapped at an Italian inn, and Diedrich Knickerbocker’s contribution of four tales of finding buried treasure. The only essays are a fairly dull series of sketches about literary life in London. The whole feels like a penny dreadful gussied up for a refined audience, and critics found it shallow and imitative, if titillating. There were also some rather prudish comments about depravity and low morals in pieces like “The German Student”, an oft-anthologized ghost story set in Paris during the Reign of Terror. The student in question, returning one stormy night past the Place de Grève, meets a beautiful young woman weeping at the very foot of the guillotine, and invites her back to his garret. The pair fall immediately in love, and she spends the night there:

Among other rubbish of the old times, the forms and ceremonies of marriage began to be considered superfluous bonds for honorable minds. Social compacts were the vogue. Wolfgang was too much of a theorist not be tainted by the liberal doctrines of the day.

“Why should we separate?” said he: “our hearts are united; in the eye of reason and honour we are as one. What need is there of sordid forms to bind high souls together?”

Pretty racy for 1824—which may explain why Tales of a Traveler sold briskly, critical opinion notwithstanding. Nonetheless Irving, stung by the reviews, began steering his writing talents into other channels—namely history and biography—rather than the genre of the short story that he had helped pioneer.

In 1826 Irving received an invitation from Alexander Hill Everett, former American Minister to Spain, to come to Madrid and look over some manuscripts dealing with Columbus and the conquest of the Americas. He wound up sojourning in Spain some three years, turning out his own biography of Columbus (A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 1828) and several other nonfiction works. A young Henry Wadsworth Longfellow visited him there, and he also formed a close friendship with Prince Dmitri Dolgorouki, a Russian diplomat.

It was with Dolgorouki that he first went to Granada and saw the Alhambra palace. After centuries of Christian neglect, rebuilding, and a recent earthquake, the old Moorish fortress was pretty much in ruins, but it captivated Irving. “It absolutely appears to me like a dream;” he wrote in a letter to a friend, “or as if I am spell bound in some fairy palace.” He took up residence there, learning the palace’s history and legends. Tales of the Alhambra (1832) is a bit like a Spanish Bracebridge Hall. Irving works in personal observations, history, sketches of offbeat characters, and a few tales set in the palace and its environs, such as “The Adventure of the Mason” (another tale about found treasure). His stories here have an almost medieval feel, hearkening back to Boccaccio and the Arabian Nights, with stock characters and little original detail. His travel writing is much more diverting. In “The Journey” he writes of meeting an old beggar “who almost had the look of a pilgrim”:

We were in a favorable mood for such a visitor; and in a freak of capricious charity gave him some silver, a loaf of fine wheaten bread, and a goblet of our choice wine of Malaga. He received them thankfully, but without any grovelling tribute of gratitude. Tasting the wine, he held it up to the light, with a slight beam of surprise in his eye, then quaffing it off at a draught; “It is many years,” said he, “since I have tasted such wine. It is a cordial to an old man’s heart.”

In the same way Irving continued his charities to his reading audience, though he led a busy life outside of his career as a writer. In 1829 he accepted a post in London as secretary to the American Minister, and later served under Martin Van Buren, presciently predicting that his boss would become president. He also visited Newstead Abbey and slept in the bed of his old admirer, Lord Byron (Byron had died in 1824).

He returned to America seventeen years after his initial trip to help Peter in England, and was welcomed home a hero. Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster lined up to greet him, and he was offered jobs as secretary of the navy, a representative in Congress, and mayor of New York—all of which he turned down. Instead he toured the American frontier (publishing A Tour of the Prairies in 1833), wrote a history of his friend John Jacob Astor’s fur company in Oregon (Astoria, 1836), met the colorful explorer Benjamin Bonneville and turned his papers into The Adventures of Captain Bonneville (1837), and bought a cottage near Tarrytown that he renovated and named “Sunnyside.” Charles Dickens was a visitor to Irving’s new pad, on one of his American book tours. His writings style is perhaps closest to Irving’s own, and his early Sketches by Boz were modeled on The Sketch Book and Bracebridge Hall. “Irving was with me at Washington yesterday,” Dickens wrote of their last encounter, “and wept heartily at parting. He is a fine fellow.”

It was Van Buren’s rival, John Tyler, who appointed Irving Minister to Spain in 1842, though he remained on good terms with Old Kinderhook. Once again he crossed the pond—this time being presented to Queen Victoria in Britain and King Louis Philippe in France. Queen Isabella II of Spain was then only twelve, and different factions were attempting to control her regency. Irving, who saw his role in part as a sort of knight protector to the young monarch, helped her steer through a civil war and other dangers, transitioning Spain from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy. But politics had taken its toll on Irving’s psyche. He wrote in an 1844 letter:

The last ten or twelve years of my life, passed among sordid speculators in the United States, and political adventurers in Spain, has shewn me so much of the dark side of human nature, that I begin to have painful doubts of my fellow man…

Returning to Sunnyside in 1846, he assumed the role of elder statesman of American letters, encouraging and assisting younger writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, William Cullen Bryant and Oliver Wendell Holmes. As Dickens wrote in an 1842 letter, “There is no living writer, and there are very few among the dead, whose approbation I should feel so proud to earn.” He also continued writing his biography of George Washington and sending occasional pieces to Knickerbocker magazine—named after his old narrator Diedrich, now an endearing term for any New Yorker, especially one with Dutch ancestry.

Although he never married, Irving’s many relations and friends made for a rich and busy old age. His nephew Pierre Munro Irving, who helped him write Astoria and would later publish The Life and Letters of Washington Irving, lived at Sunnyside with his wife in the last years of Irving’s life. In 1854 the nearby village of Dearman changed its name to Irvington in honor of its most famous resident. Five years later, in 1859, he died of a heart attack at the age of 76.

Not long before that, in 1850, the old writer had stood on the deck of a Long Island steamboat. New York was fast outgrowing Manhattan and rising up into a major world metropolis. The Atlantic telegraph would soon be completed, allowing America and Europe, those shores he had so long navigated between, to pass messages in minutes, rather than month-long sea journeys. The world was changing. He happened to meet a seven-year-old boy with his father on this boat trip, and must have appeared to them in the same legendary light that had illuminated George Washington, when he had walked into a shop on that long-ago day in his own youth. The name of the boy was Henry James.