| <- Back to main page |

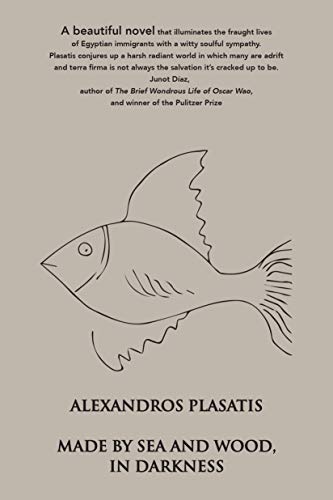

Welcome to Café Papaya, Kavala, Greece, where Angie draws, Pavlo works nights, and Egyptian fishermen come to smoke and weave their hallucinogenic tales of disaffection and longing. Your host is Alexandros Plasatis, that magician of words, idiomatic and as instantly recognizable as Ernest Hemingway or Roddy Doyle. In this collection of fourteen stories he alternates restrained, witty narration with swaggering, brassy character dialog, like that of the unstable cafe patron who insists Angie drink with him in “It Was Dawn in Salonica, Too”:

‘I’ve got a son,’ the guy said. ‘I don’t know where he is. Maybe he’s still somewhere in Salonica. The last time I saw him it was dawn. Like now.’

‘But it’s not dawn now.’

‘It was dawn, like now. He was lying on a pavement, in a busy street. He was sleeping or he was dead, I didn’t check. The needle was there. I put some money in his pocket and told him, “Good luck, friend.”’ He downed his tsipouro and finished it.

Though locals, both Pavlo and Angie seem to have more sympathy for the immigrants and outcasts than their local townsfolk. In “The Legend of Zaramarouq” (first published in Whistling Shade), Pavlo finds his hero-worship of a giant Egyptian begin to wane as he grows up, as is often the case. He’s drinking with the boss in “Their Soupsoul Laughter Echoes Dreadfully in Empty Bowls”—a story as lengthy as its title—and waiting through an endless night on both locals and foreigners. While the ever-more-drunken boss complains about an “Egyptian colony” assembling in his cafe, the immigrants know Pavlo is on their side.

‘Goodbye, our good friend.’

It was only some poor immigrants like them, and rare girls like the one with the long neck who spoke her truth, and prostitutes or beggars like Satan, who were usually polite to the waiter. Maybe because they could see in his eyes that there was a fight going on, from the outside they could see what the waiter himself couldn’t, that he was fighting his own townsfolk and was heavily beaten, and there was no chance for him. It was this lot who could understand him, and this understanding helped with the healing.

Beyond the Café Papaya lies the harbor, then the ocean, which delivers both poor immigrants and rich European tourists to its doors. And perhaps the café is Plasatis’s vision of Greece. “As if the land wanted to become sea,” he writes in “Two Arms”, where Angie smokes hashish with a fisherman named One Armed Mohammed on a slow rainy night. And his stories are like that—murky plots and disheveled conversations unraveling the layers between fact and fiction, dream and reality. Sure, these are immigrant stories—but in Plasatis’s world, everyone’s a foreign country.

- Joel Van Valin