|

One evening in the spring of 1989, I was standing in a narrow aisle on the third floor of Wilson Library at the University of Minnesota, trolling through a battered anthology of American literature. I happened upon a curious poem called "Prayer to Persephone", that went like this—

Be to her, Persephone,

All the things I might not be;

Take her head upon your knee.

She that was so proud and wild,

Flippant, arrogant and free,

She that had no need of me,

Is a little lonely child

Lost in Hell,—Persephone,

Take her head upon your knee;

Say to her, "My dear, my dear

It is not so dreadful here."

A slight little piece, to be sure, and a trifle affected (who, after all, goes around imploring the Greek goddess of the underworld?). Yet there was an empathy to the poem, something in the music of the lines and the almost child-like rhyming on the "e". It was like a hidden river. So I glanced at the name and walked a few aisles over to pick out one of the poet’s own books. I discovered that "Prayer to Persephone" was one of a series of poems for a friend who had died; and there were other, more astounding pieces. Poems that rang with music and passion and a raw, improvisational beauty. Now this, I thought, was poetry! And that’s how I met Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Okay, first off let me say I’m not the sort to fall head-over-heels for a writer. I think Thomas Mann is brilliant, Gabriella Mistral wonderfully tender, and Po Chu-i familiar as an old friend. But none of them threw me into the crazed, Beatlemania devotion of Millay. Being a Sophomore English major probably had a lot to do with it. And I’m sure not having a girlfriend at the time helped. Whatever the circumstances, within a month I’d read all her books, the poetry as well as the plays, even the letters and dull stories she wrote under the pseudonym of Nancy Boyd to pay the bills in Greenwich Village. I "burned the candle at both ends", reading her early in the morning and late at night. I read her on the weekend in the park and while riding the 16a downtown. I committed many of her poems to memory and recited them at dorm room parties. And a few years later I did my senior paper on Millay, had to specially arrange it with one of the few professors actually familiar with her poetry. By then my ardor had cooled; I’d graduated, was reading more complex, contemporary stuff. Then in 1996, tooling around New England after visiting a friend at Cornell, I found myself in Millay country, and the old passion returned. On the spur of the moment I decided to turn pilgrim, and visit the town in Maine where she grew up, the and the farm in the Berkshires where she lived in her retirement. And of course Greenwich Village, where she set fire to the ’20s.

Camden is cute fishing village on the rocky coast of Maine. It was once a shipbuilding town, but now has been made into a vacationer’s retreat, mostly New Yorkers up for the summer. Around the turn of the century Cora Millay came here with her three daughters. Edna, who went by her middle name of "Vincent", was the eldest, born in 1892. Mrs. Millay was divorced and made a hard-scrabble living as a practical nurse; her house was small and chill in the icy New England winters. Years later Millay would make this the dark background of her poetic fairy-tale, "The Ballad of the Harp Weaver":

Men say that winter

Was bad that year;

Fuel was scarce,

And food was dear.

A wind with a wolf’s head

Howled about our door,

And we burned up the chairs

And sat on the floor.

It seems an unlikely beginning for a Great American Poet, but Cora was not quite your average pauper. Educated and artistically inclined, she encouraged her high-spirited girls in music, and money was somehow found for books. Shakespeare and Catullus were read aloud, and all the Millay girls played the piano and acted in theatricals. Then there was the beauty of the coast and the wild Atlantic. Not a bad place to spend a childhood, really, and they made the best of straightened circumstances. For example one winter when the furnace went out and the burst water pipes covered the floors with ice, the Millay girls had a grand time ice skating in the kitchen.

After checking out the local souvenir shops and the tiny village museum, I hiked up Mount Megunticook, which overlooks Camden and Penobscot Bay. It was here that Edna found inspiration for what would be her most famous poem, completing it after a tumultuous visit to her dying father:

All I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood;

I turned and looked another way

And saw three islands in a bay.

The opening lines of "Renascence" echo the stifling isolation Millay must have felt in Camden. She was twenty years old, done with school and pretty much at loose ends. A few of her juvenile poems had appeared in the children’s magazine St. Nicholas, but her mother had no money for college, so prospects were dim. The long poem was a release for her emotionally; little did she know it would secure her physical release as well. In 1912 she sent it off to The Lyric Year, a popular annual poetry contest and anthology, and the story goes that one of the judges thew it into the wastebasket dismissively after reciting the first lines. Fortunately for Edna (and for all of us) one of the other judges, Ferdinand Earle, took it out, struck by something musical about the poem. In the end it won fourth prize, and created quite a fiasco as almost everyone (even the first prize winner) thought it deserved first.

The Millays were of course ecstatic, and Edna became a minor celebrity. Still, her prospects had not changed much; literature was then, as it is now, an exclusive club, and it took more than fourth prize and a literary tiff to launch a career in poetry. Millay would doubtless have remained an obscure Maine poet had it not been for the entrance, stage left, of the proverbial Fairy Godmother. She came in the person of Caroline Dow, the head of the National Training School of the YMCA in New York City, who happened upon the Millay sisters doing a rollicking piano-and-song number during a ball at a local inn. They became acquainted and, on hearing Edna’s seriousness and the Lyric Year prize, the old woman felt her deserving of better things. Dow provided Millay the money to attend Vassar, where she mixed and matched with the brightest and best.

Her course was set, and the next stop was Greenwich. It was for me as well. After spending the night in my car on an old logger’s road (where all the Stephen King books of my childhood returned vividly to the imagination) I stopped at a pretty little lighthouse on Pemaquid point, listened to the seagulls for awhile, then headed for New York.

Driving up to the toll booth for the Throg Avenue bridge in New York City, I unwittingly entered the "exact change only" lane. Not having $5 in loose coin, I sat at the unmanned toll gate a minute, at a loss, until angry shouts in a New York accent from the car behind propelled me into motion. I lifted the gate by hand and drove under it, fully expecting to be pulled over and seized by the NYPD. I wasn’t. In fact, New York was strangely inviting. Almost as if they were taking delight in contradicting their tough-love image, New Yorkers smiled at me, asked if I needed directions, were courteous in restaurants and museums. Dog walkers in Central Park waved and said hello. Edna Millay also found New York to be amiable; it’s hard to tell which of the two (Edna or New York) were more dazzled with the other.

When she came to the city in 1913, people were still in rhapsodies about "Renascence". The Poetry Society of America held a lunch for her, and Sara Teasdale invited her for (what else?) tea. Then it was off to Vassar for four years, where she routinely skipped class to finish a poem. In 1917 she was back in New York, acting with the Provincetown Players in The Angel Intrudes, and settled in Greenwich. The sprightly young poet with the red hair, green eyes, sharp wit and free manner quickly became part of the village scene. Her closest friends were Witter Bynner and Arthur Davison Ficke. Both established poets in their time, Bynner is now known, dimly, for his translations of Eastern poetry; together they were the authors of the Spectra scandal. Bynner and Ficke didn’t care for modernism, but Edna’s poetry they greatly admired for its lyricism and tradition form (her favorite being the sonnet). They weren’t alone.

It was poems like "Only Until This Cigarette Is Ended" and "Paser Mortuus Est", with their marriage of traditionalist verse with jazz-age attitudes, that made Millay the poet of the Lost Generation, much as Fitzgerald was its novelist. Both were romantic by nature but cynical about romance itself. "I Shall Forget You Presently, My Dear" cuts to the chase: it’s not the love, but the sex, that matters in the end. The sonnet appeared in Millay’s second book, A Few Figs from Thistle, which was wildly popular and is still to be easily found in used book stores. Moving from Renascence, with it’s devoutness and naivete, to the irreverent Figs, reveals how Greenwich changed her. This is the Edna St. Vincent Millay of popular myth: flippant, promiscuous and Bohemian, a female reincarnation of Byron. Her circle of acquaintance was large and her list of affairs long, including the Nicaraguan poet Salomón de la Silva (for whom she wrote "Recuerdo"), Floyd Dell, John Peale Bishop and Edmund Wilson, John Reed (the famous journalist that Warren Beatty played in "Reds") and Edgar Lee Masters (see this issue’s "Cool Dead People").

The real Millay was not quite as libertine as her reputation. Her chief interest was her poetry and her family (she had installed her mother and two sisters in Greenwich by 1918). The rollicking verses of Figs had been culled from her book Second April, because she thought them too light-weight to be considered literature. The topics in Second April are more traditional—nature, death, wandering, broken-heartedness—but infused with Millay’s innate genius for music and turn of phrase. Just what it is that makes certain of her poems so achingly beautiful is hard to explain (which is why Millay never really caught on with academics) but I’ll take a stab with Song of a Second April, just to the right there.

First of all, notice the pastoral subject and traditional form of the poem. There’s not a single metaphor to be found, or intellectual reference, or daring image. The description is general and unambiguous—we can imagine Millay walking about pretty much any country setting in New England and making these simple observations. The the rhymes give the poem a vitality, but they are common sounds ("o", "ies", "ay" etc.) and natural rather than clever. What drives the poem is the contrast of rhythm paired with images. In the first stanza, for example, the opening syllable is stressed in the first, third, and fifth lines, while it is unstressed in the second, fourth and sixth. Meanwhile we have the mixed images of "dazzling mud" and "dingy snow". Flowers are paired with butterflies, whispers with sighs. This mixing of contrasts deepens in the second and third stanzas, where hammers are paired with woodpeckers, men with boys, merry work with earnest play, rivers with brooks. Everything is in flux, all elements combining with their opposites to create a single shifting panorama: spring. At the apex of the scene we have sheep going up the hillside in the sun. But what are they paired with? Seemingly nothing. Then again—the sheep are a herd, while the "you" in the last two lines is an individual. Come to think of it, the rest of the poem is in plurals, men and rivers and orchards of woodpeckers. For all these pairings and contrasts, all this spring, there’s one final contrast: death. After all the hard work of painting spring—not just in words but in the actual music of the lines—Millay collapses it all with one catastrophic line, and one particularly stressed word, ALONE. The entire effect is done so subtly, however, that readers understand it only at an unconscious level. And therefore the reaction is emotional rather than rational. Hence Millay’s popularity, even to this day, among youth rather than intellectuals. You don’t need to read an academic essay to understand her poetry—but you do need to be able to feel it, as opposed to cognisizing it.

My own feelings, walking down Macdougal Street in Greenwich Village, was that it, like Camden, was living off of the spirit of what it had once been. Even in 1921, when Millay sailed for France, the boom of the ’20s was driving rents in the Village up, and the curious narrow streets were becoming a trendy shopping destination for the Comfortably Well Off. The American literary scene was moving, oddly enough, to a city thousands of miles away from America: Paris.

She stayed there long enough to meet many of the avant garde writers—the Benét brothers, Masters, Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda—and write "The Ballad of the Harp Weaver", for which she would win the Pulitzer Prize. Then it was off on trips to Italy, the Balklands, Vienna, and England (where, at Cambridge, she caught a glimpse of A.E. Houseman, a poet whose work she admired far above any of the modernists in Paris). She returned to New York in 1923, broke, in bad health, and over thirty.

Edna was finally ready to settle down and, with as many suitors as she had, it was not hard to find a Prince Charming. The one she settled on was Eugen Boissevain, a Dutch coffee importer and widower (his first wife, the suffragist Inez Milholland, had died in 1916). Edna had met him once a few years earlier, when he was rooming with Max Eastman, the chief editor of the Masses. Running into him at a party (they were partners in a game of charades) she proceeded to fall quickly in love. They were married soon after, in the summer of 1923. In between reading tours and trips around the world, they lived in New York, but the city had become jarring to Edna. Even in the most Bohemian moments of her Village days, the natural world of her childhood remained fixed in her mind, and her poetry was always intimately connected with it. Unlike Blake or Frost, Millay’s sheep are not metaphors for something else—they are simply sheep. The rooks and dogwood and sweet william are nothing more than birds and trees and flowers, but they form the setting for most of her work. "I shall go back to the bleak shore," Millay prophecies in one sonnet. Not quite, but in 1925 she and Eugene bought a farm near Austerlitz, New York, which they named Steepletop, and it would be their chief residence from that point on.

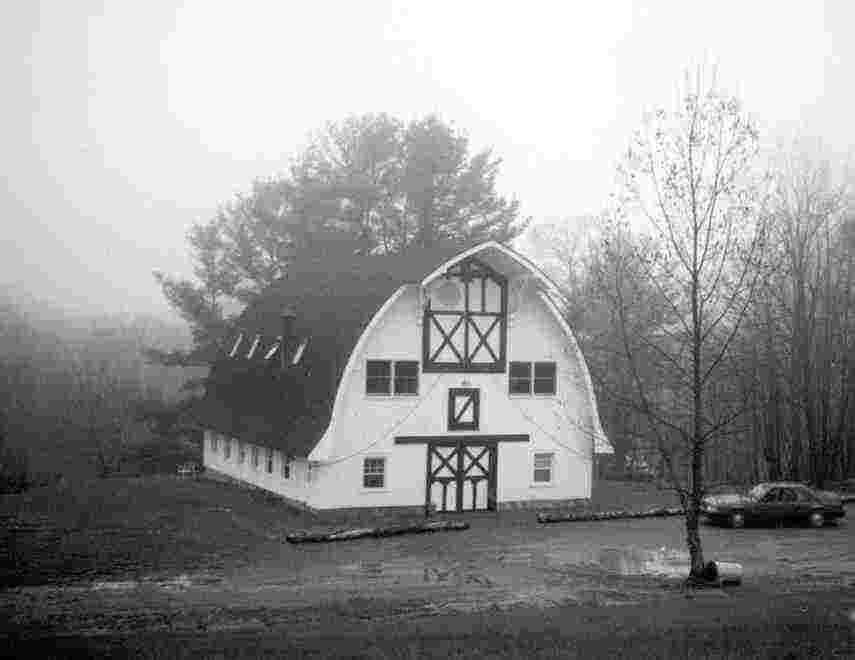

I drove to Steepletop on a quiet, mist-filled morning, threading the narrow Berkshire roads past woodlands and fallow fields. A family of ducks crossing the road was my only company, and when I arrived at Steepletop the only sound was birdsong. The large white barn has now become a writer’s colony, and I could see their cars, beaded with dew, in the drive, but no one was about. Perhaps they were up in the woods, breathing in lyric inspiration from the fresh April morning. Well, I doubt it.

Other than Caroline Dow’s patronage, which put her through Vassar, Millay never relied on outside funds such as writing grants or fellowships. Nor did she teach. In her Village days she had supported herself by acting and her Nancy Boyd pieces. It was Eugene’s money that purchased Steepletop, but the truth is that by the mid-Twenties Edna was making enough from her books to be comfortably well off. Together they ran Steepletop as a working farm, and Edna seems to have found peace in her new, quieter life. Though she had married Eugen after only a brief courtship, the marriage seems a happy one. Like the woman in "The Return from Town", Millay had got beyond the passionate but inconstant affairs of her youth. This charming little poem has the same music and pairing of subjects (boy and girl, youth and maid, man and wife) mentioned earlier, but is more settled. We have no more going back and forth on the ferry; there’s traveling, to be sure, but it ends "at my own gate".

This serenity in personal life led, as is often the case with writers, to a slow decline in Millay’s poetry. Or perhaps it was just that the spokeswoman for the "flaming youth" of the ’20s was growing older. After The Harp-Weaver was published in 1923, her verse began to take on a modernist flavor, perhaps influenced by Robinson Jeffers, whom she visited in Carmel, and her great friend Elinor Wylie. But Millay’s genius was of a different sort, musical and intuitive, and her free verse is, at best, only decent. But her later books still have many poems written in meter and rhyme, such as the title poem to The Buck in the Snow (1928) and "The Return" from Wine from These Grapes (1934). The latter is probably the most anthologized of all her pieces, and the topic was one that increasingly preoccupied her: death.

Earth does not understand her child,

Who from the loud gregarious town

Returns, depleted and defiled,

To the still woods, to fling him down.

"The Return" is an atheistic hymn. Our only "afterlife" is a physical decay that will merge us with the elemental earth: "comfort that does not comprehend". The same theme can be found in The King’s Henchman, the opera she wrote with Deems Taylor (probably best known now as the silhouetted conductor in Disney’s Fantasia). It’s based on a story from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, whose noble fatalism was a perfect match for Millay:

EADGAR

The ax ringeth in the wood.

LORDS

And thou liest here.

Her last great masterpiece, however, was a poem that defies death, "The Ballad of Chaldon Down" from Huntsman, What Quarry? (1938). She wrote the poem for Llewelyn Powys, the English author, and it commemorates a visit she made to his sickbed, traveling miles of country roads

All for to ask me only this—

As she shook out her skirts to dry,

And laughed, and looked me in the eye,

And gave me two cold hands to kiss:

That I be steadfast, that I lie

And strengthen and forbear to die.

All for to say that I must be

Son of my sires, who lived to see

The gorse in bloom at ninety-three,

All for to say good-day to me.

In 1940 another theme marched in: war poetry. Millay had been cynical of World War I, which forms the background of her 1919 anti-war play Aria da Capo, and held progressive political views (she had been one of the protestors of the Sacco-Vanzetti case). But when Hitler marched across Holland, where Boissevain had cousins, and invaded her beloved France, she felt the United States must enter the war to prevent further horrors. Edna was never under the illusion that her pro-war poems, many collected in the book Make Bright the Arrows, were anything more than propaganda. For example, in one poem she calls upon the spirit of Joan of Arc:

Joan, Joan, can you be

Still tending sheep in Domremy?

Have not voices spoken plain?

France has need of you again!

It was a noble gesture, to be sure, but having her reputation besmirched with this sort of doggerel caused Millay great strain, as she writes in a letter to Edmund Wilson: "...there is nothing on this earth which can so much get on the nerves of a good poet, as the writing of bad poetry." She had always had a nervous disposition, and now it was starting to affect her health. After 1945, she and Eugene rarely left Steepletop or Ragged Island, a small isle they had bought off the coast of Maine, not far from Camden. It was Eugen’s death in 1949, however, that finally broke her spirit. Near dawn on the 19th of October, 1950, after staying up all night reading the Aeneid, Edna St. Vincent Millay collapsed midway up the stairs at Steepletop and died of a heart attack. She had been drinking a glass of wine—when a neighbor discovered her body he saw the glass, neatly set, on the step above.

My pilgrimage was almost at an end, but I had one more stop to make. I drove most of the day, stayed over night with my aunt and uncle in Chicago, and arrived back in Minneapolis to find the quietly blooming Midwestern spring had begun. Millay had been here too, on a reading tour in 1924 which brought her, by chance, to the College of St. Catherine. The nuns at the convent had wanted to attend her poetry recitation in Minneapolis, but the rules of their order forbade them from going out at night. So Edna visited them, and struck up a friendship with Sister Ste. Helene, Dean of the college. It may seem odd that nuns would admire a volatile, devil-may-care poet like Millay. But we forget the poetry in the 1920s was much more a part of ordinary life, and poets still held the power to awe and excite; famous writers like Millay traveled about with the glamor of rock musicians or film stars. I doubt very much that nuns—or high school students, or any of the other broad segments of the population that turned out for her readings—would turn up to hear, say, Bukowski or Billy Collins. They wouldn’t even recognize the names.

Millay’s death in 1950 stands as a dividing line between two poetic eras. By then Frost had written his last great poem, "Directive", and was fading; Yeats was dead, Robert Lowell was switching from his high early style of formal rhyme to the likes of "Skunk Hour", and the American public was quickly losing patience with modernism. Youthful though it is Millay’s poetry stands firmly in the earlier, lyrical Twentieth Century. Contemplating the handsome stone buildings of St. Catherine’s, I saw that they, too, were etched by a finer, more beautiful era. And like Millay’s poems, time only seemed to have enhanced their natural beauty.

|

Photo by Arnold Genthe

God’s World

O world, I cannot hold thee close enough!

Thy winds, thy wide grey skies!

Thy mists, that roll and rise!

Thy woods, this autumn day, that ache and sag

And all but cry with colour! That gaunt crag

To crush! To lift the lean of that black bluff!

World, World, I cannot get thee close enough!

Long have I known a glory in it all,

But never knew I this:

Here such passion is

As stretcheth me apart,—Lord, I do fear

Thou’st made the world too beautiful this year;

My soul is all but out of me,—let fall

No burning leaf; prithee, let no bird call.

(from Renascence, 1917)

Two views from Mount Megunticook, showing the three mountains and three islands mentioned in Renascence

'I Shall Forget You Presently, My Dear'

I shall forget you presently, my dear,

So make the most of this, your little day,

Your little month, your little half a year,

Ere I forget, or die, or move away,

And we are done forever; by and by

I shall forget you, as I said, but now,

If you entreat me with your lovliest lie

I will protest you with my favourite vow.

I would indeed that love were longer-lived,

And oaths were not so brittle as they are,

But so it is, and nature has contrived

To struggle on without a break thus far,—

Whether or not we find what we are seeking

Is idle, biologically speaking.

(from A Few Figs from Thistles, 1921)

Song of a Second April,

April this year, not otherwise

Than April of a year ago,

Is full of whispers, full of sighs,

Of dazzling mud and dingy snow;

Hepaticas that pleased you so

Are here again, and butterflies.

There rings a hammering all day,

And shingles lie about the doors;

In orchards near and far away

The grey wood-pecker taps and bores;

And men are merry at their chores,

And children earnest at their play.

The larger streams run still and deep,

Noisy and swift the small brooks run;

Among the mullein stalks the sheep

Go up the hillside in the sun,

Pensively,—only you are gone,

You that alone I cared to keep.

(from Second April, 1921)

Recuerdo

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable—

But we looked into a fire, we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hill-top underneath the moon;

And the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

From a dozen of each we had bought somewhere;

And the sky went wan, and the wind came cold,

And the sun rose dripping, a bucketful of gold.

We were very tired, we were very merry—

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

We hailed "Good morrow, mother!" to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, "God bless you!" for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.

(from A Few Figs from Thistle, 1920)

Passer Mortuus Est

Death devours all lovely things;

Lesbia with her sparrow

Shares the darkness,—presently

Every bed is narrow.

Unremembered as old rain

Dries the sheer libation;

And the little petulant hand

Is an annotation.

After all, my erstwhile dear,

My no longer cherished,

Need we say it was not love,

Just because it perished?

(from Second April, 1921)

The barn at Steepletop

'I shall go back again to that bleak shore'

I shall go back again to the bleak shore

And build a little shanty on the sand,

In such a way that the extremist band

Of brittle seaweed will escape my door

But by a yard or two; and nevermore

Shall I return to take you by the hand;

I shall be gone to what I understand,

And happier than I ever was before.

The love that stood a moment in your eyes,

the words that lay a moment on your tongue,

Are one with all that in a moment dies,

A little under-said and over-sung.

But I shall find the sullen rocks and skies

Unchanged from what they were when I was young.

(from The Harp-Weaver, 1923)

The Return from Town

As I sat down by Saddle Stream

To bathe my dusty feet there,

A boy was standing on the bridge

Any girl would meet there.

As I went over Woody Knob

And dipped into the hollow,

A youth was coming up the hill

Any maid would follow.

Then in I turned at my own gate,—

And nothing to be sad for—

To such a man as any wife

Would pass a pretty lad for.

(from The Harp-Weaver, 1923)

Convent building at St. Catherine’s

|

Home

Home