|

| <- Back to main page |

by Jonah Smith-Bartlett

It was a surprisingly hot day in this little Illinois city. Paul told the driver to stop the car before the bridge. The driver was surprised. There was nothing here except a little dirt road lined by litter that led down steeply to the riverbank. Was he certain? Just over the bridge were the outlines of diners and gas stations. If he would only wait a moment, they could stop for a burger or a glass of iced tea. No, he needed to stretch his legs. He needed to breathe in the Midwestern air. The driver shrugged and pulled over. He was becoming accustomed to occasional odd requests like this one. Paul left the car and climbed down to the shore, slipping once and catching himself on a tree root that extended up from the ground like the taut limb of a ballet dancer he once knew. He waded out into the river until the water was up to his waist. There in the cold, dark water he remembered the dancer’s name. Priscilla. A Harlem girl who’d teased him in his youth. She’d stretched out those taut legs and claimed herself inaccessible. She was beyond his means. This was well before he became a man of great means. Where was Priscilla now? He unbuttoned and removed his shirt, pulling it over his head. He twisted it into a ball in his giant hands and tossed it to the shore. It landed inches from the water’s edge. He smiled. Not so young but not so old. Not so healthy but not so sore. Not so strong but never weak. His shoulders were still broad. His muscles were still impressive after all these years since he last stepped onto a football field. Paul held his wrists under the water. He knew many hymns about the water. Wade in the water, chillun. He could still see the scars from the night when he almost took his life. Across the world, a flight to New York, to Los Angeles, and crossing the Pacific to the desperate days in Moscow.

Jackie Robinson had almost killed him. Jackie the Dodger. Number 42. Jackie confessed—confessed wrongly—that he was a traitor to the United States of America. Jackie should have stayed in the batter’s box, Paul’s son told him. Jackie had no place in the great witch hunt. But Jackie Robinson was a hunter as much as he was a ballplayer. Jackie made him flee back to Russia. Now Malcolm, bold Malcolm, and the Nation of Islam called Jackie a traitor to the race. They tried to save the black artist’s reputation by slandering the black athlete. With his scarred wrists, Paul was called back out into the spotlight. The phone rang late into the night. Essie wouldn’t stand for any more of it. She would give all those people a piece of her mind. Who were all those people, she wondered impatiently aloud. Bayard Rustin wouldn’t leave him alone. It was time to come back to the cause of his people.

Some children stopped to watch the large man in the river. He saw them from the corner of his eye. The driver caught on. The driver tried to shoo them away. How strange he looked, Paul thought. Dressed up like a maître d’, chasing those rascals to the restaurant door.

“All right, stand down,” Paul said to the driver.

“You sure, sir?” The driver was ready to chase them down the road.

“They seem pretty harmless to me.” Five childish faces trying to figure him out. Ten pairs of eyes, blinking quickly and frequently interrupting youthful desires for explanation.

“What’s the name of this river?” he called out to them. They blinked and blinked. He wanted a conversation. The driver left them alone.

“The Monahaca,” a small girl called back, finally evaluating the situation as nonthreatening. Eight or nine years old. She had round little cheeks covered in freckles. Her blond hair was pulled back into a ponytail.

“What kind of name is that?”

“Indian,” she said, repeating the name from a schoolroom lesson on local history. “Illinois Indian.”

Anywhere, he figured, that wasn’t called the Mississippi was exactly where he was supposed to be.

“Mr. Robeson,” the driver yelled out once the children had walked on by. He was made uncomfortable by their presence. He settled back into the familiar arrangement where the will of strangers and his own will need not apply. Just him, the meek servant, and the man who directed him. “Should we keep driving? Chicago is still a couple of hours up the road.”

“Chicago isn’t going anywhere,” Paul replied. He was tired of the travel. He had been traveling for days. He traveled for years. A lifetime since his father’s church and his brother’s rebellion. A lifetime since his studies at Columbia Law. A lifetime since Priscilla and her legs. “Go ahead and take a nap in the back seat if you like. Rest up. You’ve done your duty, all right.”

Beneath the murky surface, the fish nibbled at his toes. Little one-syllable bites. They nibbled with muffled words. They were saying his name. Paul. Paul.

It was Jackie Robinson who’d almost killed him. Jackie the Dodger. Number 42. Jackie leaning forward into that polished silver microphone. Looking smart in that suit and tie. Jackie confessing all he didn’t understand to the high moral tribunal. McCarthy’s stooges. The nonathletic lifetime desk men with their weak backbones and their white hair and their sagging chins. Baseball was never Paul’s sport, but he knew that Jackie was cocky and wholly admirable when he stole home against the Yankees in the ’55 Series. The men in the stands cheered. White men in straw hats and short sleeves. Yes, they cheered and cheered for Jackie Robinson like the crowds in the amphitheaters around the world used to cheer for the great Paul Robeson.

The driver was a young kid from Kansas City named Troy. Like the city that fell through the gift of a horse. He was quickly fast asleep and Paul could hear him snoring above the sound of the currents.

Paul didn’t like Essie’s face when he told her about that room in Russia. The one where the white cracked-paint walls moved in on him like the impatient New York cars that eased through the stop signs to rush pedestrians into a hustle across the street. The one where he almost suffocated. No one else in that room seemed to suffer. No one else in that room seemed to notice when he crawled to the bathroom to submit to death. Death, the muse of many of his theatrical performances, had presented itself as an attractive alternative. There was also death’s cousin, persecution, more vile than death. The vicious cousin who chased and chased and never relented. Essie reminded him that the world was his oyster. At least it used to be. The good old days will come back around again, Paul. He didn’t like her face when he spoke about the night in Russia. A mix of fury and complete dismay.

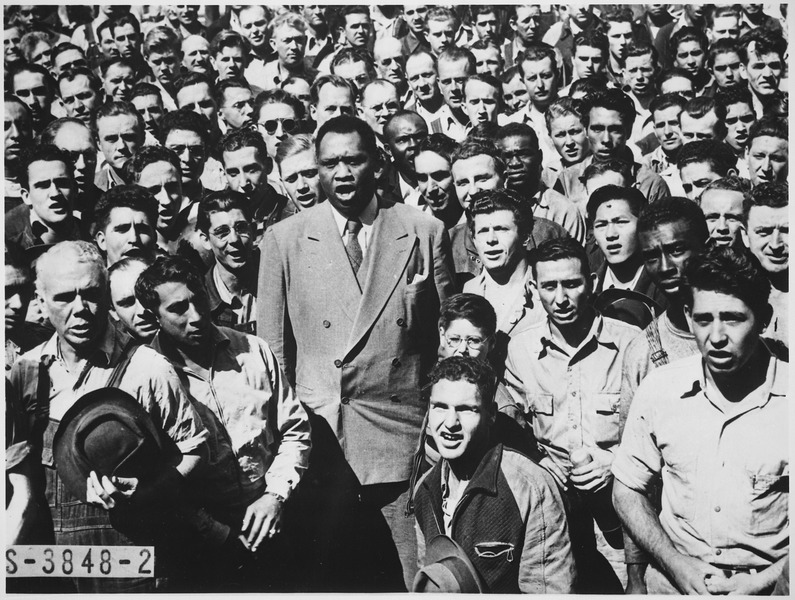

The sun tickled him. Those inquisitive children tickled him. They had no idea who he was. His records collected dust in their parents’ basements. At least once a week, he figured, some crazy man looking just like him waded out into this Indian river and tried to baptize himself anew. Local construction workers, factory workers, farmhands, union organizers—the men for whom he sang for decades. They all stood here in this spot with a drenching sadness. They dunked their heads under the water. They hoped that when they came back up, the whole world would be turned upside down. It wasn’t and those children walked on into the same-old same-old.

Paul felt his thick chest twitch. A shudder on his left side, just beneath his nipple. He was growing cold. Why hadn’t he left his slacks on the shore? They stuck to his legs in the water. They pulled tightly at all the wrong places. He felt like wearing the slacks as he waded was the dignified decision but it was ultimately the less practical choice. He shivered. He could use a towel. He looked up the hill for Troy. He watched the driver’s body shift in the car. Bayard Rustin kept calling. This Southern Civil Rights movement, Bayard said. This racial integration, Bayard said. This new American Revolution. But Paul was a man of the Internationale. He dreamed bigger.

Jackie Robinson was the first black ballplayer to play in the white man’s league. And not just to play in it but dominate it. Paul was the first black Othello to step onto the white man’s stage. Bright white lights and his Iago and his Desdemona shuffling to stay out of his shadow. For centuries men in blackface had taken that role from actors like him.

So we’re alike, Jackie. Jackie, Jackie. Why condemn me? To save your own skin?

The ponytailed girl came back. Paul saw her approaching and grinned. She was by herself. The other children went on. She asked if they wanted to go back with her. They said no. She pleaded with them and pointed out the obvious, odd narrative. A strange man is wading in the water. Alas, in all their living rooms were new television sets that displayed for them far more intriguing stories.

“What’s your name?” she called out to him after looking inside the car. Troy was still asleep. She was glad. She didn’t want to be chased off again.

“Paul,” the large man called back. He felt himself lift his shoulders and stand up tall. Hamlet told him years ago, All the world’s a stage, Paul. He would stand up tall and show his grandeur to the child. “What’s yours?”

“Louisa,” she said back. She scratched the back of her neck, then rubbed her fingernails on her blue blouse, shedding the dirt of the springtime. “What are you doing in the river?”

“To be honest,” Paul said. “I’m not entirely sure. It was a hot day and I was stuffed up in that car.”

“It’s a nice car.” She said this with the profound sincerity of one who had not yet learned the greatest adult ritual of small conversation, that of the insincere compliment.

“Thank you.” He liked her.

“Are the fish biting? River fish like to bite you.”

Paul. Paul. The fish were calling his name.

“Yes ma’am,” he said. “They sure are.”

“I hate that,” Louisa said, crossing her arms. And Paul knew this important small truth—this was all the hate that the small child could contain. She hated fish that bit her toes and to such a beautifully unreasonable, unthinkable, insane degree that she had no place left to hate anything or anyone else.

“It doesn’t bother me so much,” Paul answered.

“You’re not going to try and drown yourself, are you?”

“No,” Paul said, wondering if she indeed knew who he was before dismissing the thought as very close to impossible. “I’m not.”

“I saw a man try it once,” Louisa said. “When I was walking home from school, just like today. My friends all ran ahead and I was trying to catch up with them. I run pretty fast, but they had a head start. So I was running right by here and I looked down there at the river. And I saw a man down there right where you are. Of course I didn’t know that he wanted to drown.”

She raised her arms and shrugged. It was a good stage direction. The sign for “I don’t know.” That man’s scene was such an odd one that she could do nothing but yield to the fact that she just didn’t get it.

“I thought he might be in danger,” Louisa continued. “I thought I should save him. I yelled out, ‘You ’kay?’ and he stopped splashing and squealing and he stood up straight. And he looked at me all mean-like. ‘I’m tryin’ to drown,’ he said. And he said ‘Piss off.’ So I did like he told me. Just went home.”

“Did he drown himself?” Paul inquired. She turned her head for a new angle on her conversation partner. Perhaps she noted the sympathetic tone.

“No,” Louisa said. “I saw him three weeks later squeezing cantaloupes at the grocery store. He didn’t recognize me. And he got really angry when he thought all the melons were bad. He yelled at a cashier. I thought that was kinda funny. Three weeks ago he didn’t even want to live and all of a sudden life is so important that it can be ruined by a melon that’s a little too soft.”

Paul laughed. His deep, loud laugh. The girl, taken off guard by the mighty baritone, jumped and then laughed too. Troy woke up and rolled out of the car. He couldn’t make sense of the scene. The young girl laughing on the shore and the grown man echoing with boisterous roars from the water. Troy waved his arms at the girl, calling out, “Get! Get!” Louisa didn’t pause to object. She took off down the path from whence she’d come, kicking little spirals of dust into the air. Paul watched her until she turned around a line of trees and he could see her no longer.

“We should get going, Mr. Robeson. It’s going to be suppertime soon.”

“You’re right, Troy. You’re right. Here I come. I’m on my way.”

Paul took one long stride toward the shore and then another. He slipped off balance on what must have been a rock at his feet. He stepped on another, this one sharp. It pricked him, though it was more of an annoyance than a pain. He slipped again, and maybe this was the way it was supposed to be. Maybe he was trying to keep himself standing up and pressing onward for too long. Walking was hard. He stumbled again, and in a split-second decision lacking either rhyme or reason, Paul let himself fall. He let the cool, dark water surround his chest, his arms, his neck, his face. He felt the water run through his thick hair, cut as short as ever. He held his breath under the water. Up above, Troy was running across the shoreline. That didn’t bother him a bit.

Surrounded by water, he thought of the Spaniards to whom he sang the old gospel songs. The old slave songs. They were the men who defied Franco. They were brave men. They came armed and sat in the mud before him, drinking and nudging each other with fists and elbows as he bellowed about laying down their burdens at a riverside like this one.

Paul thought about Essie and the facts that he already knew but often kept buried. He was selfish to try and leave her. The other women made him feel like a young man again and he was gleeful in their presence. But Essie was his rock. She’d stood by his side in New York, China, Russia, and so many other places so many lifetimes ago. Then one day he’d felt the walls closing in and he was willing to let her go on standing alone. This was an act of mercy or a psychotic break. He wouldn’t drown himself over a melon. But he would drown over his own march up his own Calvary. Were you there, he thought of Essie, when they crucified your Lord?

He thought of Jackie Robinson. Jackie the Dodger. Number 42. In a different world from this one and a different fate from his mighty own, Paul would have sat in the dugout too. He would be spitting tobacco with Pee Wee Reese and the other white men. They would chant Jackie’s name with the fans who forgave him, at least for nine innings, for being black. And Jackie would follow him to Russia. He would sit backstage and Paul could wink in Jackie’s direction as he acted the most tragic of Shakespeare’s scenes. Jackie would meet those cartoonists who mocked Americans for their racism. Jackie would see the reasons for the defection of Paul’s spirit. “This is Jackie, my brother,” he would say to those men. And “Jackie, here we can both be free. And not just for nine innings. Ninety years, if God is so gracious.” Instead, Jackie stole home against the Yankees and dug his fingernails under the scuffed-up plate. Jackie’s thin arms twisted and stretched and he moaned like a dog as he pulled it up from the ground. Paul admired him—what strength! Jackie put his hand against the spike that kept the plate tightly buried in the ground. He looked at Paul, then at Pee Wee Reese, and back at Paul again. Jackie might have whispered an apology when he held that spike against Paul’s great chest. Of course he might not have either. Jackie the Dodger threw back his wrist. He drove his palm into the plate. He yelped. The crowds stood on their feet. They waved their straw hats in the air! This was a real home run, boys! Jackie watched as Paul stumbled, bleeding from the mouth, and fell at his knees. Down the third base line, Malcolm raised his hand against the crowd and yelled at the ballplayer. Traitor! Malcolm yelled and Paul prayed, “Have mercy on him.” And he didn’t petition the God in heaven, just the small good in man.

Paul Robeson pulled his head out from the water and gasped for air. And, though he doubted his body for a moment, his lungs filled up as quickly and easily as those of any healthy man half his age.

“Are you all right?” Troy waded out toward him, put his hands under the larger man’s shoulders, and pulled him to shore. “I knew we should have gone up to the diner.”

Paul didn’t have a change of clothes in the car, but he wrapped Troy’s coat around his shoulders and they drove on to Chicago. A familiar face caught him in the hotel lobby. A face he knew from the newspapers.

“Paul,” he said. “My name’s James Farmer. Bayard asked me to come talk to you. Said I might not be any more convincing than him but that I couldn’t do any worse. Does that sound fair?”

“Sounds fair,” Paul replied with a smile.

“Seems like you’re drenched,” Farmer said, looking him up and down with a strangely endearing sneer.

“I almost drowned today.”

“Well, thank Christ you didn’t,” Farmer replied. “Death can wait a while. Life needs you, Paul. It needs you desperately.”