| <- Back to main page |

|

“If it’s one thing I hate, it’s the movies. Don’t even mention them to me,” Holden Caulfield complains in The Catcher in the Rye. But we’ve all been dazzled by the silver screen in one way or another. In this issue, Whistling Shade’s editors and guest contributors write about ten films that touched their lives.

Put off by black and white movies like The Maltese Falcon? Nothing in the film is black and white. Forget the femme fatale who walks into Sam Spade’s office in Act 1—even Spade himself and his partner have their own secrets and duplicity to maintain, though not directly relevant to the main deception of the plot. Nearly eighty years later, the film’s craftsmanship and the dark senselessness of the characters’ drives make it just as relevant as it was then.

It’s a mystery film for sure: But instead of a detective being tasked to track down a killer, the setup is reversed. The detectives are engaged, one of them is killed, and the cynical and wily Sam Spade, played by Humphrey Bogart, must then determine why and with whom exactly he’s gotten mixed up with. In one sense, these answers are perhaps never entirely clear. The characters have names, but are they their real names? Their motivations are fungible, their alliances switch at a moment’s notice. The movie’s love affair, if one would even call it that, is entirely unconvincing—but that’s the point. Sam Spade and “Bridget O'Shaughnessy” are lost at sea in their own deceptions, and in their final confrontation, he muses over whether he even loves her at all.

To recount the plot of the film would simply emphasize its absurdity. On false pretenses, Spade is drawn into a web of intrigue between three individuals all searching for a legendary treasure, the gem-encrusted statuette of the film’s title. Mary Astor, Peter Lorre and Sidney Greenstreet all play their parts masterfully, each of them a legend-making caricature and different kind of liar. Events start to come so quickly and chaotically that it would be hard to detail the shifting alliances, feints and decoys along the way. The main thing is that when the police finally catch him with the would-be treasure-hunters in his apartment, Spade proves himself to be just as good a liar as his opponents. He enters into their duplicitous fraternity all too easily. Offered $5000 for the Falcon, Spade a few hours later offers it to a rival buyer for $10,000 without blinking—an offer to sell an object he’s never seen and in fact had never even heard of twenty-four hours earlier. Buried in the snappy patter, words cease to have their meanings, such as when Spade tells his loyal secretary, almost without irony, “You’re a good man, sister.”

Certainly the film is notable for being Bogart’s first great role as well as John Huston’s directorial debut. Bogart, slim and slight of figure, never fires a gun in the film, despite being confronted by them again and again. He fights his opponents off with lies, half-truths and verbal deflections, maneuvering them to the point where he can finally sacrifice the hapless bullyboy who’s been doomed to be his patsy from the moment he walks onscreen (played by the outstanding character actor Elisha Cook Jr.)

But it’s the web of deceit and the joyless way Sam Spade navigates it that still resonates for the modern viewer. At the film’s conclusion, he’s run out of lies he can tell himself to justify shielding his on-again off-again lover from the police. The legendary treasures, the tissue-thin alliances, the love story that the film haltingly nods at—they are in the final words of Sam Spade, merely “the stuff that dreams are made of.”

- Julian Bernick

Dario Argento's 1977 Technicolor art-horror masterpiece Suspiria begins in a stark, colorless void. In a startling credit sequence, white letters appear against a black backdrop as a brutal, percussive soundtrack by the Italian band Goblin thunders in the background. That ominous, singular music, more radical than the atonal 1960s film soundscapes of Toru Takemitsu, louder and more malevolent than Black Sabbath, sets the dislocating tone for a dreamlike tour de force.

Against the still-blackened screen, the viewer hears an expository voice-over of almost childlike simplicity. We’re informed that the young American ballerina Suzy Bannion has decided to perfect her ballet studies at “the most famous school of dance in Europe” in Freiburg, Germany. She has just landed.

Nothing that follows in Suspiria achieves that level of forthright, monochrome certainty. The screen explodes into color as we follow Suzy (Jessica Harper) walking through an airport bathed in brothel-red illumination, finally passing through a windswept portal into a thunderstorm awash in unearthly blue light. Arriving at the academy, she’s mysteriously denied entrance and sees another student, Pat Hingle (Eva Axen) run through the rain against a dense tableau of trees, a scene replicated nearly frame-by-frame 30 years later in the Danish mystery series Forbrydelsen (The Killing).

Pat seeks refuge at a friend’s apartment, muttering about an imprecise threat at the academy. Soon, a surreal menace comes to life. As Goblin’s cacophonous soundtrack returns, disembodied eyes appear outside the window, a hairy demonic arm smashes through the glass, and the fugitive student is under attack, finally crashing through an expanse of stained glass, hanged by her mysterious assailant. Under her swaying feet, a puddle of blood teasingly suggests a witch riding a broomstick.

Arriving at the school the next morning, Suzy meets the vice-directress Madam Blanc, played by old-Hollywood starlet Joan Bennett, in a vast chamber that combines M.C. Escher wallpaper, startling coloration that could have sprung from the symbolist imagination of J.K. Huysmans, and garishly serpentine balustrades. She’s informed, in an eerily dispassionate tone, of Pat’s violent demise. That scene, with its bracing fusion of flamboyant visuals and dreamlike dialogue, sets the stage for a journey into a rabbit hole of otherworldly set pieces. Suzy joins forces with fellow student Sara (Stefania Casini) to uncover the academy’s legacy of witchcraft and defeat the evil designs of its enigmatic, apparently immortal directress.

There is a recognizable story in Suspiria, but it cheerfully sheds the comforts of narrative logic for the ineffable atmosphere of dreams. Argento’s wife Daria Nicolodi based her screenplay on the real-life experiences of her grandmother, who attended an acting academy where black magic was as much a pedagogical focus as dance and drama. But its most powerful inspiration lies in Thomas De Quincy’s Suspiria de Profundis, whose three Sorrows (a parallel to the three Graces and three Fates), are re-imagined by Nicolodi as all-powerful sorceresses: Mater Lacrymarum, Our Lady of Tears; Mater Suspiriorum, Our Lady of Sighs; and Mater Tenebrarum, Our Lady of Darkness. De Quincy’s eccentric work is a dream wrapped in a hallucination, populated by impenetrable ideas and archetypes that could only spring from a profoundly fertile, if distressed imagination. Suspiria is just as inimitable. We expect even the most fantastic fiction and films to replicate some forces of lived experience, but Argento offers a nightmarish fairy tale whose sights, sounds and sense of narrative gravity resemble nothing else on earth.

- Sten Johnson

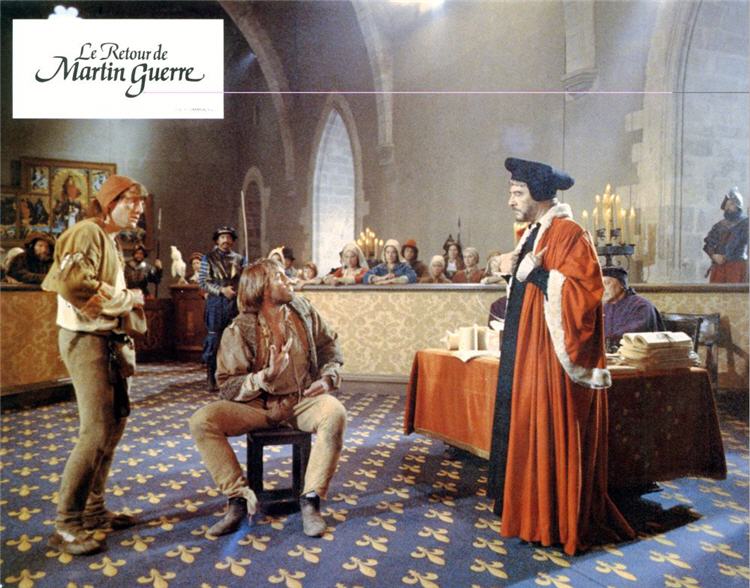

If your high school was anything like mine, you probably saw some pretty awful movies in class, like Sarah T.—Portrait of a Teenage Alcoholic. So, you could understand my excitement in being shown a beautiful, riveting love story in French class, La Retour de Martin Guerre (The Return of Martin Guerre, a 1982 French film with English subtitles starring Gerard Depardieu).

This is perhaps where my love of this rich social historical tale began, in silent gratitude of getting out of conjugating verbs and listening to boring and incomprehensible French lectures. For three days, I sat among twenty-six junior and senior classmates, all of us mesmerized by Depardieu and co-star Nathalie Baye in this amazing film based on a true story.

The tale goes like this: In 1538 in France, a fourteen-year-old boy named Martin Guerre married Bertrande de Rols. In 1548, after fathering one son, Martin disappears after being accused of stealing grain from his father. A man with similar looks and details of Martin’s life arrives on the scene in 1557 and convinces most of the village that he is the real Martin. He lives with Bertrande and her son for three years and they have two more children, with one daughter surviving.

But problems arise when Martin tries to get part of his father’s inheritance from his uncle, Pierre, who then accuses Martin of being an imposter. Eventually, this “Martin’s” true identity comes out as Arnaud du Tilh, a poor man from a neighboring village. This leaves Bertrande in a difficult place —to lie about the imposter and claim him as her husband or risk being an adulteress. She remains silent. Dramatically, the real Martin Guerre returns during the trial and the imposter is convicted and hanged for adultery and fraud. The real Guerre did not return to his wife and family for many years.

La Retour de Martin Guerre stayed fairly true to history and is a compelling foreign drama. Despite its rich cinematography, attention to period detail and beautifully executed performances by Depardieu and Baye, the movie grossed a mere $4.3 million at the box office.

Then enters Warner Brothers, with the cocky Hollywood belief that it can remake and improve any foreign film. Although some movie critics disagree, in the case of Sommersby (a 1993 Martin Guerre adaptation starring Richard Gere and Jodie Foster), Warner Brothers succeeded and grossed $50 million domestically and $90 million overseas.

The setting of Sommersby strayed vastly from the original sixteenth century story of Martin Guerre, catapulting it into the post-Civil War South. Warner Brothers built the set in Hidden Valley, Virginia, in the George Washington National Forest where there are no power lines and few signs of modern civilization. To create an even more believable setting, they planted, cultivated and harvested thirty acres of tobacco just for the movie.

The three-hundred-year leap forward in time was not the only thing Warner Brothers had going for Sommersby. Richard Gere’s ruggedly sexy swagger, flirty eyes and half-cocked smile coupled with the playful coyness of Jodie Foster (who had just won Best Actress in a Leading Role in 1991 for The Silence of the Lambs) was a magnificent match. Gere (Jack Sommersby) drew you into the mystery of his identity while Foster (Laurel Townsend) drew out your empathy for the deep struggle of a wife’s passionate dilemma. The love story that ensues between Jack and Laurel is intense, ending with a suspenseful court battle for Jack.

The love story for Foster did not end on the screen with Gere. It was on the set of Sommersby that she met the production manager Cydney Bernard, who became her longtime partner from 1993-2008 and father of her two children.

Gere, a Tibetan Buddhist who studies under the Dalai Lama, had the opportunity to take his Buddhist practice into real life on the set, personally rescuing livestock during dangerous torrential floods and escorting them to higher ground.

At least one notable anachronism occurred in the film: a fiddle fitted with a twentieth century chin piece played during the homecoming dance. The African American judge (James Earl Jones) who tried the Sommersby case was also extremely unlikely, as most black judges of the time only presided over African American court cases.

The Simpsons, The Bridge on the River Kwai, Mad Men and various novel and plays have also adapted plots based on the Martin Guerre story. Why do so many storylines continue to revolve around Martin Guerre? Perhaps it’s the possibility of taking another man’s life, community and bed and more or less getting away with it—at least for a while. The idea that the grass is greener somewhere else is a rather common human perception, but it tends to end badly—time and time again.

- Deanna Reiter

As much as I deplore Mel Gibson’s recent controversial statements and admit the somewhat romantic campiness of the film, Braveheart still possesses a deep part of my sensitive self, which defies continuous double-thoughts about it. Though much of its seemingly essentialist near-doctrine of masculine and feminine, freedom-lover and oppressor, directly contradicts more modern social constructionist notions of agency and choice, the film moves me still, flawed and brilliant in its own troubling identity, a medieval romance that eventually transcends its own nature and becomes a tale of true bravery and selflessness.

Braveheart is at the immediate level a medieval romance. It follows the tradition of the chivalric romances, in particular Lancelot, the Knight of Cart, where the ideals of courtly love and martial prowess are both emphasized. Indeed, the legendary and historical character William Wallace is portrayed as both a lover and a fighter. He is forced into doing noble killings out of love lost. For his Guinevere, the Lady Murron of his clan village, is executed unjustly, and he seeks justice in a knightly, noble manner. This one unjust act prods the knight to seek a greater cause, freedom, and to fight a greater beast, the tyrannical English, as the movie portrays them. This valiant warrior then goes on to free his people. However, the one who truly slays the beast, the dastardly King Edward I “Long Shanks”, is a princess, and this is where the film departs from that chivalric tradition, to some extent.

Princess Isabelle, married to the neglectful Prince Edward, longs for true love. She finds it in William Wallace, whom she makes love to in a diplomatic meeting.1 They conceive a child. This child will be King Edward III of England. She lets the current King Edward know on his deathbed, when he cannot speak or move, but can hear. This is the ultimate punishment for his horrid treatment of the Scots and others. He is trapped in his own body as his most dear possession is given to his ultimate enemy: his throne is given to the Scots. Through all this, the newly empowered Princess displays a command of her husband. She is the one in charge. She is the strong leader.

In the end, Braveheart escapes its own hierarchy-perpetuating tale to become one that actually empowers women, turning the medieval romance on its head. It banishes the essentialist notion that only men can be powerful commanders, and its message is actually in accord with the Feminist movement already at full steam in the Nineties, that people aren’t constructed by nature, but that people are in command of their own selves, their own fates.

- Robert Menge

It’s a beautiful scene, shot in a public park that’s covered with equal parts of smoke and fog. The sky is overcast, while honking car horns compete with the drone of industry.

This seems like an unlikely backdrop for romance.

But when it’s over, the audience believes that love can take root anywhere.

Even in Hoboken.

In acting, understanding how to create romantic tension is impressive, but holding it for its maximum length and knowing when to release it is an art form. Hold the tension too long, the tension will dissipate.

Throughout the history of film, nobody utilized this technique as effectively as Marlon Brando.

The “White Glove Scene” starts with Eva Marie Saint’s character exhibiting a virginal quality. Her posture is erect and her wardrobe is immaculate. Look deeper however and you might see that her life is at a tipping point and she might be open to desire.

Brando portrays a washed up boxer whose future was over before it started, but he’s incredibly handsome and cloaked with an animal magnetism that isn’t easily ignored.

As they begin walking and the dialog starts, it’s easy for me to tune out their conversation. Both parties are so awkward and vulnerable that their words hold little value. The things they say make me uncomfortable, so instead I focus on their gestures.

Brando’s body language indicates he is out of his element in the presence of his refined companion. Gum chomping, hands buried deep in his pockets, feet dragging and mumbling are the best he can offer to convey his feelings.

Every time I watch this, it reminds me of the helplessness I’ve experienced falling in love.

As Brando and Eva Marie Saint begin to walk across a playground, she reaches into her pocket to pull out a pair of gloves, but one of them slips from her grasp and Brando instinctually bends over to pick it up—but he doesn’t give it back, and that’s where the magic begins.

When Eva Marie Saint reaches to take back her glove, Brando isn’t paying attention because his complete focus is on his new treasure. As he inspects it, a small smirk forms as he holds the glove up and begins picking off imaginary pieces of lint.

This moment is paramount, not just because it’s spontaneous, but because it’s the first time the audience gets to witness the sensitive side of our protagonist thug.

With a second attempt, Eva Marie Saint politely charges Brando, but he evades her by falling backward onto a swing-set, where he swings back and forth slowly until he pulls the tiny glove onto his massive left hand. It’s at this point where Eva Marie Saint begins to lose it, and you can see she’s getting annoyed. I’ve watched this scene dozens of times and I still can’t tell if that look of anguish on Eva Marie Saint’s face belongs to her, or to her character.

Had any other actor played opposite of her, they would have simply picked up the glove and returned it.

But Brando isn’t any other actor, and that’s why this scene surpasses spectacular.

- Danny Klecko

My Man Jeeves, P.G. Wodehouse’s first collection of comic stories about the hapless Bertie Wooster and his genius valet, was published in 1919. It started a rage for stories where the servant was more capable than the master, and the below-stairs world secretly ran the above-stairs one. Eric Hatch, a writer for The New Yorker, capitalized on the trend with 1101 Park Avenue (1935), a short novel originally serialized as Irene, the Stubborn Girl in the magazine Liberty. The story follows the rich and eccentric Bullock family of Park Avenue, New York, who hire a bum from the city dump named Godfrey to be their butler. Once in coat and tails, Godfrey’s soon running the place with Jeeves-like efficiency, while capturing the heart of Irene, the Bullock’s younger daughter.

Universal Studios, sensing a hit, bought movie rights from Hatch and brought him on board to write the screenplay. My Man Godfrey, starring William Powell as Godfrey and Carole Lombard as Irene, was filmed in two months in 1936, smack in the middle of the Great Depression. The opening sequence, with bums warming their hands over a burning barrel in a dump by the East river, is a sobering reminder of the era. But as soon as the rival Bullock sisters, Cornelia and Irene, sweep in with their chauffeured cars, each looking to collect a “lost man” for their charity scavenger hunt, viewers are taken on a flight of fancy through the glittering halls of the indolently rich, where horses can be found in the library and musical protégés imitate gorillas.

It’s an ensemble cast, and everyone has at least one memorable line; in fact My Man Godfrey was the first (and one of the only) films with Academy Award nominations in all four acting categories (being a simple “screwball comedy”, it won none of them). We’ve got Gail Patrick as the spoiled rich girl Cornelia, Alice Brady as the dithering Mrs. Bullock, Mischa Auer as her hungry protégé Carlo, Jean Dixon as the bantering maid, and stubby Eugene Pallette as the much put-upon Mr. Bullock who declares, after revealing his business dealings might land him in jail: “But if I do go to jail, it’ll be the first peace I’ve had in twenty years!”

At the heart of the film, though, is the romance between Godfrey and Irene. Powell and Lombard, who actually were briefly married in real life (they had been divorced for three years when they made Godfrey) had enough silver screen chemistry left to set the film above the typical madcap frolics of the time. Godfrey is in some ways like his British prototype. He cures Mrs. Bullock of seeing “pixies” with Jeeves’ favorite hangover cure: tomato juice and Worcestershire sauce. And he even quips, when Irene notices that his pocket has a hole in it, “I told Jeeves to lay out my other coat.” But there are darker waters running through Powell’s character. Godfrey seems to have a mysterious past—echoing old ballads and fairy tales, where the poor woodcutter’s son or servant who wins the lady’s affections turns out, in the end, to be a prince. He’d been a drunk, had an unhappy love affair, and had even contemplated suicide at one point. But his spirit and honorable character remain unbroken. “There are two kinds of people: those who fight the idea of being pushed in the river, and the other kind,” he tells his friend Tommy Gray. And to Irene he confides, “You helped me to find myself, and I’m grateful,” even while resisting her romantic advances.

Lombard could have played her character with the “dumb blonde” persona that appears in so many films from the era, and was perfected by Marilyn Monroe. Instead, her Irene is more like an idiot-savant, zany and yet, in a child-like way, profound. There’s something pure about her devotion to Godfrey, echoing the universal values of reciprocity and the golden rule (which is actually quoted in the film, though it’s Powell’s line).

Irene: You’ve done something for me—I wish I could do something for you.

Godfrey: Why?

Irene: Because you did something for me! Don’t you see?

And she could be speaking for the entire Depression era when she declares:

I’ve decided I don’t want to play any more games with human beings as objects—it’s kind of sordid when you think about it—I mean when you think it over.

Irene seems to float about in a different world; wealth and position have no meaning for her. And many of her lines have a curious, reciprocal balance to them:

It’s funny how some things make you think of other things.

I know what you mean if you know what I mean.

Just this morning you were sitting on my bed, and now I’m sitting on yours.

Everywhere I went, everyone was Godfrey.

After all, one room is just like any other room.

Speaking of rooms: My Man Godfrey has an interesting correlation between its open spaces and closed spaces: the dark city dump can be paired with Godfrey’s subterranean butler’s room; the Bullock’s noisy, crowded drawing room is like the Waldorf Ritz hotel in miniature; and the intimate Carrie bar where Godfrey meets Tommy recalls Irene’s light, dreamy bedroom. Then there’s the matter of Cornelia’s pearls. They disappear midway through the film, only to suddenly resurface in the denouement, after being used to save the family’s bacon. This symbol of transmutation mirrors Godfrey’s rehabilitation. Another point of symmetry: shortly after helping Godfrey wash the dishes, Irene pretends to faint, and he puts her in the shower. Now she’s the one being washed (or shall we say baptized?), and her eyes fly open.

Such literary-like devices are more in keeping with a film like Citizen Kane, but My Man Godfrey tosses them off almost effortlessly, with no fanfare and only a moment of screen time. Other films of the era, such as The Thin Man Powell had done the year before, have this close triangulation between plot, setting and dialogue, but in My Man Godfrey this art is taken to heights typically seen only in Shakespeare’s comedies. Whether this was the work of Hatch and fellow screen writer Morrie Ryskind, director Gregory La Cava, the actors involved, or simply a happy coincidence, is unknown. Also apparently lost to history is Wodehouse’s reaction to the film, which he probably saw (he was writing his own scripts for Hollywood at the time). Fortunately, My Man Godfrey itself is in no danger of becoming a “lost film” about a lost man: it was added to the National Film Registry in 1999, and is still easily located.

- Joel Van Valin

In 1955, back when a big-screen movie could be made for just over $1 million dollars, I saw my first film, Lili. I was five years old. The story involves an orphaned French girl befriended by a circus troupe. By being part of a popular puppet show, she learns to love the curmudgeonly puppeteer behind the curtain. My teenage brother took me to what he thought was a kid show because it featured a sweet young woman, singing, and puppets. What would my Methodist parents have said had they known the movie also included material more appropriate for adult audiences?

I can’t call Lili my favorite movie, but rather one that my memory favors, having held on to it for the longest time. Talk about an impressionable young mind! The images and theme song came into me like light on a camera’s film, and it marked me as its own. Images and characters have surfaced over the years in dreams and even figured in a recurring nightmare where a curtain on a puppet show is torn open to reveal the angry face of the puppeteer. Sunnier scenes also periodically flash on what poet William Wordsworth called “the inward eye, Which is the bliss of solitude,” such as when Lili runs back and into the arms of her one true love.

Lili starred the cheerful, sprightly Leslie Caron. Even back then, I knew that the main character was bubbly and cute, like my older sisters. The puppets that Lili talked to were entertaining, especially when they became large-sized and walked alongside the girl on her journey out of town. Later when I saw another charming young woman befriended by the puppet-like Scarecrow, Lion and Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz, it had echoes of the scene from Lili.

When I saw the movie a second time, a half-century after the first, I realized how many details I had paid attention to, but wasn’t capable of understanding fully. For example, I remembered that Lili climbed partway up a ladder, but of course I didn’t know about absolute despair and that she was planning suicide.

Here’s another example of how a child can be impressed by details, but lack understanding: I responded to the unpleasantness of a character in the movie. (The story on which the screenplay was based called him “The Man Who Hated People”.) As an adult, I could take into consideration how his war wounds affected his life’s dream to be a dancer. I saw him in a more sympathetic light. And what about the philandering cad? Any of the business connected with womanizing had been way over my head, but when I saw the movie as a grown-up, his slick tricks were obvious.

Most of us have had the experience of getting a song in our minds that plays over and over as if an unseen hand controls the repeat button. The song in the show, which is “Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo,” is like that for me. Its refrain, “A song of love is a sad song,” can start the looping, perhaps because I bonded early with the similarly sentimental and melancholic Lieder that my German grandmother listened to. Remember the man who falls in love with Lorelei and drowns? I’m a sucker for that song, too.

- Margaret Hasse

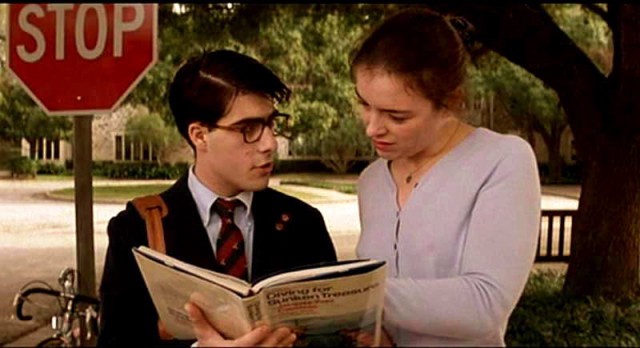

In Rushmore, fantasy, naiveté, and adulthood melancholy are intertwined in the unlikely friendship between fifteen-year-old private school failure Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), and fifty-year-old businessman Herman Blume (Bill Murray) as they compete for the affections of teacher Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams). The droll banter between Blume and Fischer highlights the frustrations of two developmentally stunted individuals who, despite their difference in age, are blind to the hamartia of their grandiose attempts to project an image of genius, success, and sacrifice to Mrs. Cross. The irony and absurdity of this gently dark comedy lies in that fact that both Fischer’s and Blume’s personal lives are crumbling even as their romantic gestures toward Cross escalate to extremes.

Fischer presents as an ambitious geek who is unmoved by his outcast status, creating and running numerous social clubs at Rushmore Academy even as his failing grades threaten his continued enrollment. His unwavering belief in his own exceptionality becomes the backdrop of his one-sided, obsessive, doomed love affair with his teacher that begins and ends as a self-created fiction. In this upside-down social world, Fischer and his cohorts behave with the entitlement of jaded, world-weary adults while displaying preadolescent innocence and naiveté. Enter Herman Blume, whose friendship with Max becomes subsumed by his quest to relieve midlife loneliness through his burgeoning infatuation with an introverted teacher at Rushmore. Both characters bring out the worst in each other as their drive and creative energies become more and more focused on sabotaging each other’s attempts to win Cross’ heart. Once he falls in love, Fischer is undeterred when Cross points out the fact that he is too young for her. As Fischer behaves more like an (arrogant) adult, Blume’s insecurities cause him to become more like his own teenage sons (both spoiled bullies), whom he loathes.

Throughout the escalating rivalry Cross is little more than a symbol for the validation that benighted Fischer and Blume crave. While pursuing the same fantasy, Blume and Fischer both receive a temporary reprieve from the unpleasant realities of their lives, but only at the price of their dignity and peace of mind that would be within their grasp if they faced their fears rather than running away from them. The film delivers the message that redemption is attainable, but only after foolish behavior is checked by comeuppance. The friendship between Blume and Fischer demonstrates that we never really outgrow our capacity to engage in tunnel vision through wishful thinking, often to humorous—if tragic—effect.

Rushmore established director Wes Anderson’s reputation for stylish, subtly funny set props, the juxtaposition between innocence and jadedness, as well as his penchant for crafting emotionally blunted characters who communicate through droll banter. The backgrounds in Anderson’s subsequent films are so intentionally crafted that they overshadow the characters, and become substitutes for dilute stories. And while Anderson’s distinctly beautiful, visual style is so often evident in his more recent films, none of them is as affecting as Rushmore, perhaps because none of their protagonists capture the essence of anything so universal as childhood naiveté and unrequited love.

- Justin Teerlinck

Equinox is a supernatural film from 1971 that I first encountered on the daily summer afternoon feature when I was growing up. Upon the first viewing, I was intrigued and watched it several more times when it came on over the years. I didn’t know it at the time, but the film is famous for its micro budget, yet received distribution and made money. It has an interesting history and is worth checking out from the library just to see the resourcefulness of its creators of art on a scant budget. As an adult, I see the film a little differently, but still enjoy the creepy vibes it gave me as a kid, and still think it’s an interesting supernatural suspense story. Some may see it as a product of its time and budget, and maybe a little campy, but I still get into the story and take it seriously on that story craft level.

For me, Equinox qualifies as a good film because it meets all my criteria: it is absorbing, it takes me away, it is relatable, it is plausible, it shows me something different or what I could not otherwise experience, it is creative and imaginative, it moves me and makes me feel something, and it has an interesting story that unfolds in a realistic manner and holds my attention. This film creeped me out as a child, especially the open-ended denouement. The story is supernatural in a way that is plausible and felt as though I was an active participant, rather than just a passive viewer. It felt as though this story could happen to me and my friends.

The story involves some young adults who go into the woods to search for a lost scientist (played by sci-fi author Fritz Leiber). They find an ancient book of spells. A park ranger (actually a demon in disguise) wants the book back and so unleashes some unpleasantness, including monsters and other surprises which torment the group. The group gets lost, they find a hidden castle, they encounter monsters, the suspense builds and builds, they fight demons, and some of them don’t get out. But do they get away from the demons? That is the open-ended question and leaves a lasting eerie vibe, thus making a successful supernatural story.

The monsters are cool. The story unfolds in a gripping way that keeps you hanging on for the next obstacle to get around. The film made me feel something when I was a kid —the creeps, the chills, eerie vibes, the thrill of exploring the unknown woods, and suspense in wondering if they will get out of the woods in one piece. It may feel a little dated compared to the technology available today and some of the cultural mores of that time, but if you think in terms of the late 60s, that may help in getting into the cultural context and situation that is presented.

The Criterion Collection DVD release includes both versions of this movie—the original shorter version, and the version that was expanded by the distributor for wide release. The longer version is better than the shorter because it spreads the suspense out. Inspired by the work of H.P. Lovecraft, the film originally played in theaters and drive-ins, then became a cult hit via the late late show and midnight showings in theaters.

- Tony Rauch

1 Editor’s note: In actuality, William Wallace was just a child when Edward III was born. Isabella’s lover was Roger Mortimer, with whom she deposed her husband, Edward II, and installed her son on the throne. Edward III was, however, almost certainly the actual son of Edward II and grandson of Edward I.