| <- Back to main page |

|

by Alexandros Plasatis

Pavlo began working in Café Papaya the summer he turned fourteen. Morning shifts. The terrace was big and busy. He learnt quickly, served quickly, and liked it busy. The customers were difficult. Too much froth in their coffee, not enough ice-cubes in their pop, pigeon droppings on the seats, ants crawling up the trees, leaves falling from the trees, flies, hot hot hot, oh too hot, ah yeah, ah they liked the trees’ shadows, ah nice, ah so nice, the sun moved, oh no, they had to move into the shade again. Some made jokes, but they made the same jokes every day. Some were all right, some were good, and Zaramarouq was Egyptian.

Pavlo didn’t know that Zaramarouq was Egyptian. He didn’t care what he was. He only admired him. Zaramarouq usually came to the café at around 11am with three or four Greek fishermen, who were all around thirty-five or forty. It was really busy at 11am, coffees coffees coffees, but every time Pavlo went to take Zaramarouq’s order, suddenly everything would hush. So strange how everything hushed. Zaramarouq would give a simple greeting to Pavlo, like, ‘What’s up, Pavlo? How’s everything? HAHA!’ Pavlo liked the way Zaramarouq spoke, because he liked simple things and because his voice was strong and crisp. His accent made some words sound like breaking crackers. He thought that his laughter was a giant’s laughter. In Pavlo’s eyes, Zaramarouq was a giant, wind-beaten and sea-beaten with deep wrinkles. They looked good, the deep wrinkles. Huge and solid arms and thighs he had. And broad shoulders and enormous fists with great big knuckles, and fingers full of net-cuts, and brown, wild hair, thick-like-needles hair, hair in all directions, mad hair. This strange giant always ordered his frappé pulling ridiculous faces—imitating someone who strains to shit, an orgasmic woman, a sobbing boy, stuff like that—never failing to make Pavlo giggle.

When one of his companions behaved like the other customers and dared to complain to Pavlo about a coffee or something, Zaramarouq would cut them short: ‘Shut up, you moaning arsehole! You got your period again?’ His companions laughed at these quips, but their eyes betrayed discomfort and even fear. Without a care, Zaramarouq would laugh his giant laughter and turn to Pavlo: ‘Take your time, Pavlo, bring us the coffee whenever you feel like it.’ Pavlo, balancing on one hand a tray full of pop and coffees, would say nothing, he would only laugh with his big friend, making sure he didn’t spill the drinks. And when he realized that the customers became impatient with him just standing there and looking at Zaramarouq, he would go back to serving quickly. So the hours and the days in the café would pass quickly, until the next time Zaramarouq would come to hold the morning back.

Something else that hushed the café’s terrace was when Zaramarouq told dirty stories to his companions. Pavlo couldn’t get enough of these. The young waiter worked out a system so as not to appear that he was slacking: when serving, he always tried to walk past Zaramarouq, and if he heard him telling one of his tales, he would go to a nearby table with his cloth and give it a wipe down, then the backs of the chairs and the legs of the chairs, listening and stealing glances at the storyteller who stirred his imagination:

‘…and she sits exactly opposite me. EXACTLY opposite. And she opens her legs! Like THIS!’ Zaramarouq opened his legs, pulled aside his shorts with one hand, ‘and she does THIS!’ he brushed the fingers up and down near his genitals: ‘Like this, like this… And she flashes at me her cunt-lips!’ and, knowing that the young waiter was watching him, he would catch Pavlo’s eye and pull a face: ‘Un-fucking-believable’—then get on with the story.

And so, the waitering mornings continued on in that way, busy and giggly and dirty, until the day Zaramarouq got into a fight.

It was 2:30 pm, the shift was going to finish soon and Pavlo was sitting by the bar, waiting for the time to pass. The terrace was almost empty. Zaramarouq and his companions, two Greek fishermen in their fifties, were sitting at the far corner and had been served. Served also was a group of four Greek fishermen who were sitting not far from the bar. Zaho Castrioti was one of them. Pavlo didn’t like Zaho Castrioti. Zaho had short blond hair, he was getting bald, and was the same age as Zaramarouq and maybe as big as him. But he always seemed annoyed about something and Pavlo was a bit scared of him.

Two or three tables away from Zaho’s group, two couples of foreign tourists settled down, well-dressed and well-groomed, the sort that didn’t come often to Café Papaya. They seemed to be travellers on their way to the opposite island, Thassos, and as they were waiting for the ferry, they had decided to have a break and freshen up.

‘Hi. What would you like, please?’

Two frappes, two fresh orange juices.

Served.

Pavlo was glad that these blond travellers stopped at the café where he was working. From here, they could see so many nice things. The fishermen who were scattered all along the harborside, sitting cross-legged in front of the caiques, mending nets. They could see the hill with the Old Town, its fort and walls and aqueduct, the roofs of the Imaret—left behind by Byzantines, Venetians, Ottomans. Lots of history. Maybe they liked history. Pavlo didn’t know who built what, he would be embarrassed if they asked him, he hoped they didn’t. The sky was blue and the sea was bluer and the island opposite was dark dark green. The blond travellers had all that to take in and they had good coffee to keep their eyes alert and nice thick shadows from the lemon trees to keep them cool.

That was what Pavlo was thinking, sitting on the barstool by himself, smiling to no-one, when an old man appeared. A tall, skinny, drunk old man with a fishermen’s hat and a white beard that shimmered under the hot sun. Ah, this old man used to be a kind fisherman, Pavlo imagined, who had taught the wood of his boat to be friends with the sea. Pavlo imagined that the old man had weakened over the years and one day the sea-worm inside him died, and he turned to wine, and drank and drank to mix some red in all that dead blue.

Anyway. The old fisherman walked slowly between tables, grabbing onto the backs of chairs to keep steady. He took his time walking and finally stopped in front of Zaho Castrioti’s table and muttered something.

Zaho ignored him and the old man stood there, looking at Zaho with his drunk old eyes. Zaho never looked at him, he only looked annoyed. The old man muttered again. Zaho, without looking at him, said, ‘Go away.’

From the corner of the terrace, Zaramarouq’s voice was heard: ‘Leave the grandpa alone, you hear me?’

Zaho turned his head slowly and stared at Zaramarouq. Five seconds. He looked away.

The old man closed his eyes, he wiped spittle from his mouth and the hairs around it, and dried his palm on his trousers. He muttered away. Zaho looked straight ahead and took a deep breath and the old man kept on trying to tell him something, and Zaho snapped: ‘GET THE HELL OUT OF HERE AND GO AND FUCK YOURSELF,’ and all of a sudden Zaramarouq shot off like a cannonball towards Zaho Castrioti: ‘I TOLD YOU TO LEAVE THE GRANDPA ALONE.’ A heavy glass ashtray was hanging from Zaramarouq’s fingers, it glistened as he was bull-running through the terrace, forcing his way straight ahead, no need to manoeuvre between tables: tables and chairs that stood in his way took a tumble, ashtrays twirled, menus shot away, everything making way for Zaramarouq to attack, everything half-frightened and half-excited to see him in action.

Zaho hadn’t got time to move from his chair. Zaramarouq smashed the ashtray into Zaho’s balding head and now the two giants charged each other, brow to brow, eye to eye, a mutual headlock.

Pavlo eyed-up Zaho’s companions. They didn’t move. He eyed-up Zaramarouq’s companions. They didn’t move. Eyed-up the travellers. They didn’t move either.

Pavlo moved. He jumped up from his barstool and ran towards the giants. He didn’t know what he would do once he got there, he just ran, and, when he got close enough, he took a leap and smashed a shoulder against Zaho’s body.

He found himself on the floor, and the last thing he saw before everything turned dark was Zaramarouq, kneeling over him, absorbing Zaho’s boots and punches from behind.

When his vision returned, the tiles around him were sprayed with dried blood. He looked up. Zaramarouq wasn’t there. Zaho’s companions weren’t there. The old man wasn’t there. Pavlo thought that Zaho Castrioti wasn’t there either, but then he saw Zaho on the floor, between tables and chairs. The two Greek fishermen in their fifties sliced open a cigarette and put wisps of tobacco on the cuts on his head, they poured water on his bloody face.

The young waiter got up. Got a broom and a shovel and brushed away broken glass and mugs and ashtrays. He put tables and chairs back up the right way, brought replacement ashtrays, wiped the menus clean and slid them under the ashtrays. Café Papaya looked all right again.

A police car pulled up in front of the café.

One of the fishermen helped Zaho away.

Two policemen took Pavlo to one side. Questions were asked, answers given: ‘Yeah, there was a fight. No, don’t really know them. A blond fisherman, bald really, and someone else. Um… It was the blond’s fault.’

The other Greek fisherman approached. ‘It was no-one’s fault. The guys will sort it out between themselves.’

The policemen looked up at him.

‘In a peaceful way,’ the fisherman added.

The policemen left.

The fisherman left.

Only the blond travellers remained.

And Pavlo looked at the travellers, smiled at them. Then he went inside to wash the blood away. It wasn’t his blood. He found a black t-shirt, took off his white, stained shirt, and changed it. When he came back out the travellers had gone. He took his tray and went over to clear their table. In between the empty cups and glasses, there was a small pile of coins. A tip.

A few days later, Pavlo heard that Zaho Castrioti had been coming down to the harbour every night, carrying a gun with him, searching all caiques, looking for Zaramarouq to kill. But Pavlo wasn’t worried about Zaramarouq. Zaramarouq could beat up Zaho anytime, even if Zaho had a gun, because, for Pavlo, Zaramarouq was a legend.

Weeks passed by, months, and Zaramarouq came less and less to the café, until he stopped coming at all. Mid-September Pavlo went back to school and worked in Café Papaya for only a few hours on weekends. Sometimes, on Saturday afternoons, he saw Zaramarouq on his red motorbike, riding slowly in front of the café and turning his head to give a wave. Other times, when Pavlo strolled around the harbour, he saw Zaramarouq on a caique, sitting cross-legged on a corner of the deck, working on the nets with his back against the town. His back was always turned against the town. ‘Why is your back always turned against the town?’ he wanted to ask, but didn’t. Because he knew that Zaramarouq was a legend, and that’s what legends do, they have their backs against whole towns, and hold a needle and a piece of net, and when they feel like it, they look up and gaze out to sea.

And as years passed by, Pavlo almost forgot about Zaramarouq. He came to know other Egyptians, most of the hundred or so who worked on the caiques. The locals looked down on them, but Pavlo took a liking to these Egyptians, they were easy going and didn’t moan or complain when the café was busy and he was slow to serve them. Word had spread in their community that when he was a boy he had defended the big Egyptian, and on his harbour strolls they would come over to talk with him, and he felt their admiration.

It was on one of these strolls, a hot afternoon down at the port-authorities place, where the fishermen were getting ready to go on their voyage, unloading ice from trucks into the caiques, that Pavlo heard Zaramarouq calling his name. The big man was leaning against a wooden pillar, half-hidden under the shadow of the wheel-house.

Pavlo stepped closer to the caique.

Zaramarouq’s voice cut him short: ‘What you think about life in the harbour, Pavlo? You think it’s like the old days?’

‘I guess so,’ Pavlo shouted. Pavlo had to shout. Zaramarouq just spoke.

‘No, it’s not like the old days, Pavlo. And you know why? Because now the only thing everyone cares about is money. You got money? Everyone’s your friend. No money? Go and fuck yourself.’

Now, this was how ordinary people talked, Pavlo thought. If it wasn’t for Zaramarouq, he would say yeah yeah, just to get on with it. The world was full of ordinary people, but Zaramarouq was Zaramarouq, so Pavlo said, ‘No, that’s not what I think.’

‘I can’t hear you, Pavlo. What did you say?’

Pavlo shouted: ‘That’s not what I think. That’s what you think.’

Zaramarouq stepped out of the shadow. He looked angry. But then, a small group of Egyptians approached Pavlo and cut Zaramarouq’s step short. A group of Egyptians who had returned a few days ago from Ezbit El Burg and had presents for him, presents from Al Qahirah. They exchanged three kisses, Egyptian style, and Pavlo went on with his stroll, leaving Zaramarouq behind, feeling a bit of a legend himself.

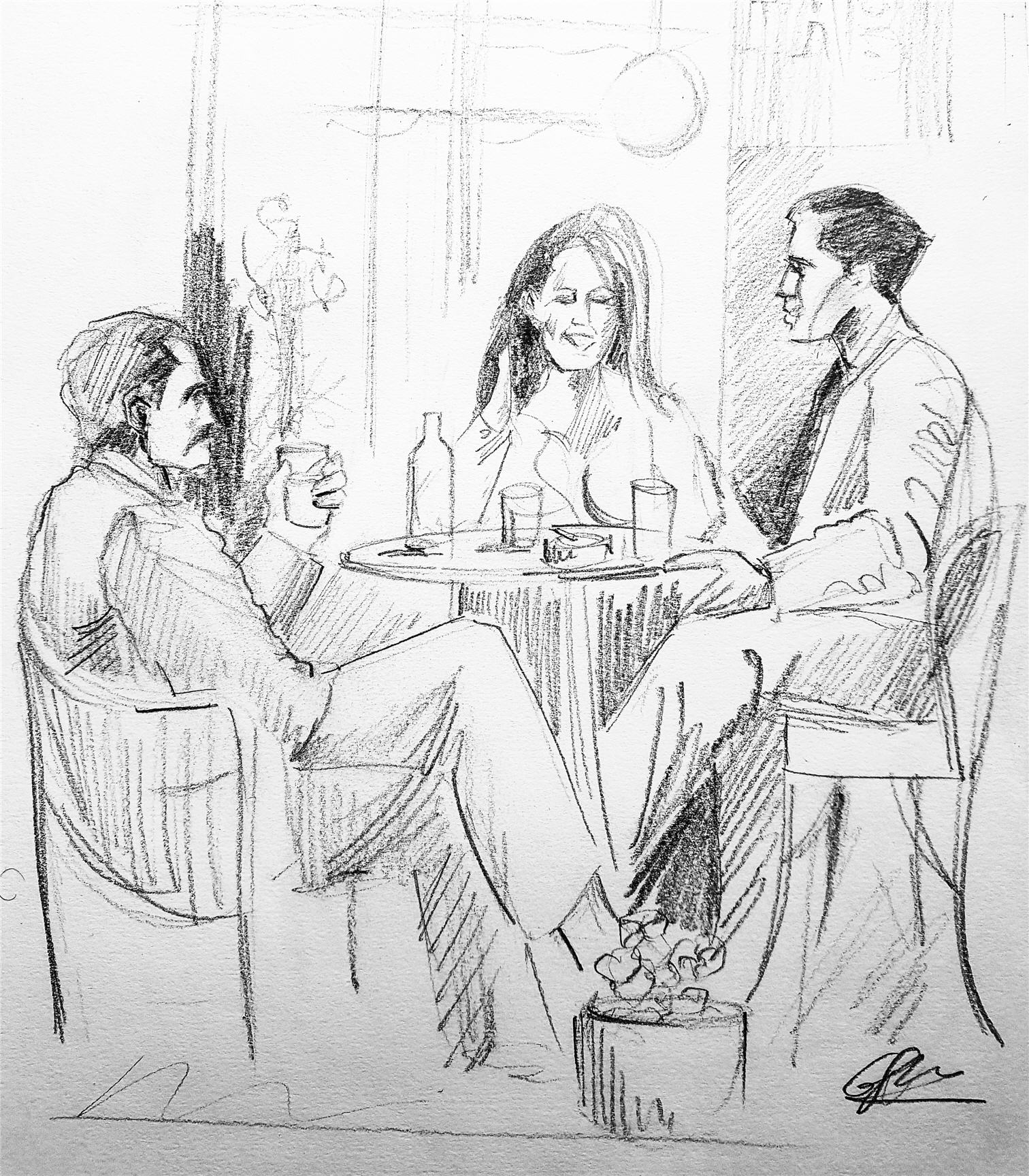

Pavlo was a man when his old friend came to the café again. That was the first time he had seen Zaramarouq for years. He came with his wife, Soula. It was a late summer evening and Pavlo wasn’t on duty, he was just hanging around. He liked just hanging around. The three of them sat at a table out on the terrace. Introductions were made. Then:

‘But his name is Yiorgo Ahmoud. Don’t tell me that you didn’t know it? God, why didn’t you tell him, Yiorgo? Of course, how would you know if no-one had told you? Zara-however you called him wasn’t even his Egyptian name. That’s no name at all, never heard it before. Yes, Yiorgo is the name he adopted when we got married. You didn’t know he was married? Now now…’

Soula was Greek and Soula liked talking and so Soula talked: they had been married for twenty years; her husband came to Greece twenty-seven years ago; they would go back to Egypt sometimes for holidays; they had a son; their son was Pavlo’s age; and then on and on and on.

Pavlo caught the attention of Angie the waitress. Nodded. She came over, flashed a smile. ‘What can I get you guys?’

Soula and Zaramarouq wanted hot chocolate.

‘And you, Pavlo?’ Angie flashed another smile.

‘Nah. I’m all right, cheers.’

Angie left.

Soula went on. ‘Ah, yes, when I got married to Yiorgo…’

Zaramarouq hadn’t changed much. Big and strong with mad hair and all. But he didn’t talk a great deal, and, when he did talk, he seemed to be controlling his voice, trying to keep it down.

Hot chocolate was served.

‘You sure you don’t want anything, Pavlo?’ Angie asked.

Yes, he was sure.

Soula kept on talking, Zaramarouq listening passively, Pavlo thinking about how much he had admired this man when he was a boy, and saying to himself that his only purpose at that table now, his only purpose, was to bring back the legend of Zaramarouq. But he shouldn’t push things. He had to take it easy. Be patient.

Lighters were stroked, paper and tobacco burned, silver plumes of smoke rose in the dark cool evening, and Soula went on to talk about the big stories on the news those days, the wild behaviour of the tourists, especially those from Britain. The TV reported incidents of men going around dressed as women, nuns usually; of young females pulling up their tops and flashing their breasts to locals. Soula’s cheeks turned pink as she talked, and she lowered her eyes down on her own breasts. She had large breasts. Pavlo looked at her breasts and Zaramarouq looked at her breasts and Soula saw them looking at her breasts. Then she asked why those foreign tourists behave like that. Neither Zaramarouq nor Pavlo answered, so Soula decided to provide her own explanation:

‘You see, these poor girls are away from home, that’s why they do these things. They feel like doing something wild. Do you think our girls are any better? The other night—oh my God, Pavlo—we went with Yiorgo to this new beach-bar on the other side of town—have you ever been to that one, Pavlo?—and we were scandalized!’

Pavlo leaned forward. ‘Oh yeah?’

‘Yes, Pavlo. Hahaha. Goodness me!’

Pavlo kept his eyes on Soula: ‘What happened in that beach-bar?’

‘Well…’ she re-adjusted her bum on the seat. ‘We were sitting by a small table right on the sand and from the darkness near us, behind the rocks, we heard… we heard…’ she paused and looked at her husband.

Pavlo sat back. Eyed Zaramarouq. He was looking at his wife, they were smiling at each other. Pavlo turned to Soula. ‘So what did you hear from the darkness?’

‘We heard: “Ah yes, yes, ah more, yes, yes, more…” Haha! My dear Pavlo, it was one girl and three men! One girl and three men. And the telly shows the English girls. Why? Are our girls any better? She took all three of them together, my dear Pavlo. Together. And she kept moaning. Haha…’

Pavlo and Zaramarouq laughed. Pavlo’s laughter was stronger.

Soula sighed. Sipped her drink. Went on: ‘Ah, Pavlo, Pavlo. Now you’re in the best period of your life. Whatever you’ve got to do, you’ll do it now. Once you grow up, forget everything. You’ll get married and the wildest thing to do is come to Café Papaya and drink hot chocolate. You’ll have kids, commitments. I got married and enslaved myself. What did I get out of it?’

‘Oi! Bitch!’ Zaramarouq snapped in such a loud and quirky voice that it made Pavlo sit back and laugh. ‘Are you saying now that I don’t take you out? It’s you who wants to stay home. I keep telling you to go to places, but you don’t like this, you don’t like that–’

‘No, my sweetheart, no. I’m not complaining. It’s something else that I’m trying to say to Pavlo.’

Pavlo stubbed out his cigarette and had a good look at Soula. She was plump. Curvy plump. Jelly, bouncy, rubbery plump. Not hanging-down plump. He had noticed before that she had a nice, big round bum. Her skin was tanned and smooth and shiny, and her eyes big and green and almond-shaped. And as he kept staring at her, he saw those big green eyes giving a sidelong glance to her husband, he saw how her lips bent and formed a smile, how slowly those lips parted: ‘If they come here, why don’t we go to England?’ Her cheeks turned pink again.

The couple looked at each other. She said: ‘Would you take me there? Would you take me to London?’

‘I would take you to London.’ Then, to Pavlo. ‘But I can’t really take her to London. My passport has been seized.’

‘How come?’

‘Did some bullshit back in Egypt.’

‘Oh… And your Greek passport?’

‘Haven’t got a Greek passport. They won’t give me one.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because they keep playing with their little willies, that’s why not.’

‘Yes, Pavlo,’ Soula snapped. ‘After twenty-seven years here and married to a Greek, they won’t give him a passport. Every year I’ve got to sign papers so that he won’t be deported.’

‘Bollocks to that,’ said Pavlo.

‘Exactly, Pavlo. Bollocks,’ said Zaramarouq. ‘If I wanted to, I could get Greek citizenship. I could have proper papers and everything. You know how many times they told me to go down to Athens and get a passport? But you know what else they said? They said that I’ll have to get it through a window, Pavlo, not through the door. And I don’t like getting in through windows. Me, Pavlo, if I ever get in, I’ll get in through the door.’

Pavlo smiled. Zaramarouq didn’t.

But Pavlo kept on smiling because he knew now that Zaramarouq was still a great man. He decided that now was the time to pull out the greatness of Zaramarouq, to turn him, once again, into a legend. He had no idea how he would do that. He only knew where to begin. They would talk about something that they had never talked about before, maybe that would help. But hot chocolate? A night like that, with stars and lemon trees and sea and legends and a cheerful woman, and they were having hot chocolate? They needed a drink first.

‘I’ll buy you a beer,’ Pavlo said. ‘Can I buy you a beer?’

The couple looked at each other. Smiled. ‘Of course you can.’

Pavlo glanced at Angie. She was busy at the bar preparing an order. He went over and brought beers and glasses, and, while beers were poured and cigarettes lit, Pavlo looked at Zaramarouq and said, ‘You remember when–’

‘Yeah I remember,’ said Zaramarouq. ‘You want to talk about the fight with Zaho Castrioti, don’t you?’

Pavlo and Zaramarouq had a few good gulps of beer. It was nice, cool beer, and they were warm inside.

Soula looked at them, had a sip.

Zaramarouq went on.

‘Of course I remember.’ He took a drag. ‘HAHA!’ It was a giant’s haha. ‘HA! I remember well.’ More beer downed. ‘You should stay out of these things. You could get hurt.’ Plumes of smoke lingered around the table, and behind the silver smoke, Soula’s big green eyes had something new as she looked at her husband who talked with passion. ‘Did you see the others? No-one had moved.’ Her eyes shot towards Pavlo. ‘Yes, I remember that fight with the arsehole. But Zaho Castrioti was an arsehole and that’s it. I remember that fight and I remember many more fights with other arseholes, but there’s a fight I can’t forget.’

‘What fight?’

Zaramarouq put the glass down: ‘The fight with Dino.’

‘Ah!’ Soula jumped up and clapped her hands. ‘Ah yes yes! Dino! The fight with Dino!’

‘You know Dino, the boxing champion?’

‘Heard the name before.’

‘Well,’ said Zaramarouq. ‘Listen now.’

Pavlo and Soula leaned forward, and Zaramarouq began:

‘I knew Dino and Dino knew me. He used to drink a lot at that period. He owned a tiny bar and his wife was the only barwoman. So one night I go to his bar and drink my whisky and Dino is already pissed. After a while he turns to me and says: “Oi! Leave my wife alone!” I say, “What’re you talking about, Dino? I’ve done nothing.” “You grabbed her arse! I SAW YOU GRABBING HER ARSE!” I tell him that I didn’t grab her arse, but he’s really angry. “You grabbed her arse, YOU DARK BASTARD.” He leaps at me. I push him away. He throws a couple of punches, but it’s easy to block him, he’s drunk. ‘You fake Muslim,’ he says, ‘you married a Christian, you drink alcohol, you changed your name, you fake Muslim.’ Fake Muslim? I’m losing it. I hit him and he falls. I beat the shit out of him and leave him unconscious.

‘One morning he finds me in the harbour and tells me to watch my step. He says nothing else.

‘Some time passes and I go to another friend’s tiny bar, again for a whisky. While I have my drink, I see Dino coming in, sober. I say to myself, “That’s it. I must say my prayers now and fight the champion.” That’s what I said to myself, Pavlo. “How am I going to get through this one?”

‘HA!

‘He grabs a stool and smashes it against my face, and I fight blind for a while. I feel the blows coming in quick and I can’t breathe. I manage to get in two or three punches. When I regain my vision, I break his nose. He had me after that, he cornered me and turned my face into mince. Into MINCE he turned my face. I left the bar and my whole face was a wound. Mince and blood. Here, ask Soula. When I went home, she couldn’t recognise me.’

Zaramarouq reached for his beer and finished it. ‘Pavlo, Pavlo. I was beaten, Pavlo. Beaten.’

Pavlo caught the attention of Angie the waitress. Nodded.

Soula put her hand over her husband’s hand. Her fingers ran through his great big knuckles. ‘Let’s forget it, Yiorgo.’

Angie flashed a smile. ‘What can I get you guys?’

‘Beer,’ said Zaramarouq.