Whistling Shade

Winter 2010

Poetry

Marshland Dusk - John Philip Johnson

The Wedding Room - Shanan Ballam

Fiction

Angle Side Angle - Mary Lynn Reed

There Is Always More Work to be Done - Dave Barrett

The Relief Printer - Jessica Rae Hahn

Reviews

The Nine Scoundrels by Deanna Reiter

Whistling Shade's Literary Cafe Review

Memoir

My Meeting with Mengele - Maryla Neuman

Essay

Eating Your Words in a Prague Cafe - John-Ivan Palmer

John Dos Passos, a View from Left Field - Hugh Mahoney

Lost Writers of Minnesota: Clifford D. Simak - Joel Van Valin

Columns

Shading Dealings - Race-based Literary Journals

Fun Patrol

I Never Promised You a Shit Garden

Justin Teerlinck

The bus dropped us off in a remote border area between Guatemala and Honduras. A small, three-legged dog and a cab driver with a toothpick in between toothless gums awaited us. With no other transportation in sight, we gingerly climbed into his dirty, dilapidated Pinto.

"Hey," he said. "Me llamo es Francisco. Do you need any cocaina? Want to see some ruinas?"

Darcy said, "I thought this town we were going to was Copan Ruinas, not Cocaine Ruinas."

"No shit," said Laura.

"How about it man?" I said in Spanish. "Do you know any rooms where to spend the nights for us?"

"Si," he countered. "You want to be a real campesino? Work the farm? For 400 Lempira you live with my sister, Blanca, and my son, Jose will teach you to farming. He has a large brain, with the college. He have a...a place called...uh...what you say it? Ah! `Much Broken Bird Now Flying.' Many gringos go and teach the children or make the farming. You know," he said, "like burro." Francisco then pretended to make donkey ears and said "ooooo-eeeeee! Ha!"

"Hey...." said Laura. "Keep your eyes on the road! We're in the mountains! Are you trying to kill us?"

"I cannot kill you," Francisco retorted philosophically. "Only the Big Mr. Above will take you in His time."

"Have you taken liquor drunk?" I asked in Spanish. Francisco's breath seemed to greet us in midair. He made no sign that he heard my remark, but began to sing loudly and off-key and the tiny, beat up Pinto careened around gravelly hairpin turns. I leaned over and looked at my companions. The back seat of a cab driven by a religious drunk over mountain passes seemed like the best place to make a quick, if not the best informed, decision. The girls shrugged their shoulders.

"Why not?" said Darcy. "We talked about volunteering. Maybe Blanca will feed us too." Laura nodded her approval.

Blanca Rosa invited us into her life as though we'd always been her children. More than a host, she was our mother. She fed us three gigantic meals a day and gave us "lunches" to take with us into the cool reaches of the nearby mountains that were so large they ended up feeding half the village. We watched her enrapt as her thick arms and vine-like tendons slapped tortilla dough back and forth. One day she explained how to do it. With practice, Laura and Darcy's efforts yielded perfect tortillas. Blanca giggled and covered her face as my asymmetrical, uneven creations turned into the misshapen offspring of maize, water and untrainable hands.

"Julio," she said. "You should learn Spanish. I think you would be better at that than tortilla making."

We lived in a hotel which was also Blanca's house. She cooked and we ate with her at her table with her alcoholic husband and youngest child, a precocious eight-year-old named Perla, who clomped around in oversized cowboy boots with our Spanish-English dictionary, trying to absorb all she could. The next day, we got up at six o'clock and piled in the back of a small Nissan pickup for our journey to the mountains. The driver leaned out the window.

"I am Jose," he said. "I run Much Broken Bird Now Flying. You will pay 600 Lempira and then you will work. Do you want to be teachers or farmers?" Could it really be that simple? Weren't there going to be questions about what qualified us for either position? Wasn't there an interview? No, this was Honduras.

It took an hour for the tiny truck to claw its way up the rutted 4x4 dirt track to the small school. Darcy, Laura and I squatted as best we could along with three teachers, two children, a hoe, pick-axe, shovel, machete and a chicken or two. Arms and legs hung off the sides. We tried to point the sharp edges of tools away from ourselves. Nobody made eye contact, a futile attempt at maintaining Western industrialized standards of personal space while we sat smooshed against each other, flesh to flesh like cans of fresh, pickled gringo. In many ways the best part was the morning ride to the school. At several overpasses, we watched the sun rise over other green mountains, sending clouds of mist and fog rolling off their tips, to tumble lazily down toward the valley. We smelled the diesel exhaust mixed with the jungle odors and listened to the roar of the motor as the driver pushed his oversized load over precariously unbalanced ruts in the muddy road.

The teachers were British, one a middle-aged stout woman who looked and talked like one of the nanny ladies on Nanny 911. "Oh dear! Oh my!" she was always saying when the truck bounced up and down. The other one was a shy, young, beautiful girl with red, tightly ponytailed hair who barely spoke, and burst out in nervous giggles whenever I said anything. They both looked like members of the Royal Family. They were brought to the jungle school on a pre-planned program they signed up for back home. Neither one was a teacher or training to be one. They spoke less Spanish than we did. Every time we saw them they seemed exhausted, strung out but amused. But they were smart, and they were willing to go with the flow. Like many other Western travelers we met, we seemed to have nothing in common with them, but somehow bonded in the face of the universal feeling of overwhelming disorientation we confronted every day in Central America.

After we got out of the truck, another one pulled up behind us. It was Jose's assistant. Jose handed us several bags of seeds. "This one is cilantro," he said. "This one is parsley. This one is the tomatoes. This one-how you say it-ah, the cu-cumbers. You will dig the holes. You will plant the seeds."

"Are you going to teach us farming now?" asked Darcy.

"I just did," he said. "I will take you to Roberto. He will show you where to dig."

"That's it?" Laura asked. "How will we know what to do?"

"Roberto, he will show you. Is mas facil, very easy, even for a gringa. After this day you will not see me. Please work hard because these people need the help. I will now take you to Roberto."

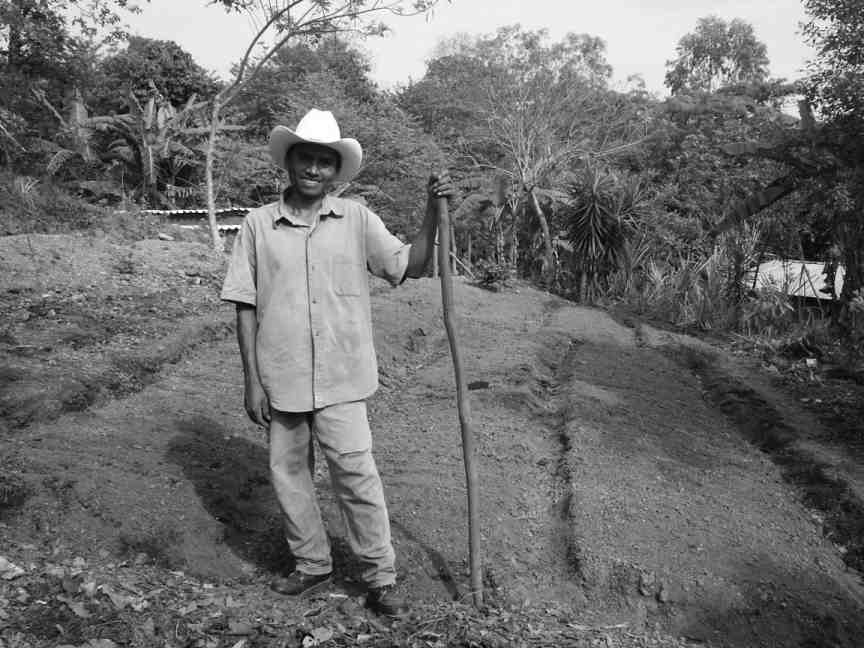

I had assumed that we would be working more or less where the truck dropped us off, but it was another mile and a half hike further up the road into higher elevations, then down into a steep valley on a tiny trail hacked through the jungle, to Roberto's house. We wended our way through a jungle thicket and found a small, acre-wide clearing. There stood a tiny, windowless shack, a clothesline tied to a tree, several steel buckets and pails. There were loose dogs, chickens and living fence posts sprouting moss and leaves, strung together with barbed wire. We smelled a cooking fire and saw smoke emanating from the house. A man emerged wearing dirty white trousers and a white cowboy hat. The man smiled a wide, shy grin. He shook our hands. "Hola. Me llamo Roberto," he said. We introduced ourselves and Jose and Roberto talked in Spanish to the side. Jose gestured toward us and Roberto nodded, unable to hide a smirk. Jose touched Roberto's shoulder and kept talking. Jose kept saying the word "work" and "very good" and pointing to us. It sounded like he was trying to convince Roberto to do something. Finally, Roberto tipped his hat a little and nodded his head. "Okay," he said.

"What did he say?" I asked Jose.

"He says Darcy is very skinny. He is worried that you are too...delicado? Sensitive? For this. He says if you die he doesn't want to get into trouble."

"Why would we die," Laura asked, irritated. "Just because we're women?"

"Tell him we'll be fiiiiiiine," Darcy said, smiling. "I was raised on a farm. We had tons of Mexicans. We did this all the time." She gave Roberto a thumbs up and he smiled. A woman peered out from inside the shack. She was stirring a pot or something. She sighed and looked at us and said something in an irritated tone of voice to Roberto. It was clear that we were not fully welcome here, or trusted.

Roberto just smiled a mellow smile, shrugged his shoulders and laughed. "Okay," he said. "Es okay."

"Muy bien," said Jose. "Gracias. I will now leave you here. Can you find your way back? Good. Let me know if there are any problems. Please work hard here. Good luck." With that, Jose walked back into the jungle and we stood awkwardly, leaning on our pick axe, hoe and shovel in the company of people we could barely communicate with. I instinctively realized that this was as close as I would ever come to the sense of vulnerability, humility and shock that every cultural anthropologist must feel when they embark on their first ethnographic assignment.

When Jose was gone Roberto pointed to a patch of ground filled with trees and rocks next to the house. "El jardìn nuevò," he said. Our faces dropped slightly. We thought we would be helping plow up old fields and re-planting, not breaking new earth in the mountainous jungle. Without further instruction, we began digging, hitting and flinging away at the earth as though we were trying to kill it. Immediately, Roberto started laughing. He laughed so hard that he bent over at the waist and touched his toes. Then he fell to one knee. There were tears in his eyes.

"Are we doing it wrong?" Darcy said in English.

Roberto dismissed the question with a wave of his hand. "Muy bien, muy bien."

After we turned up the soil I took the pick axe and started swinging away at a stump. I raised the heavy handled thing over my shoulder again and again, crashing it into the stump for what seemed like an hour. Sweat poured from my brow in a steady drizzle, watering the disturbed soil at my feet. I would show this motherfucker who was a lazy gringo! Roberto shook his head. Finally he came over and gave me a few pointers. "No, like this," he said, holding the axe a certain way. I began to hit the stump in the way he showed me while he hacked away at it with a machete. In about ten minutes we were both hauling the massive, rotting chunk of wood out of the ground, along with several thousand fire ants and their nest, which immediately began to swarm over my forearms while leaving Roberto alone. I dropped the stump and started slapping myself and hollering really loud. Just then a gaggle of local women walked by on the trail, carrying loads of laundry in baskets. They all began laughing and pointing, as if we were some sort of traveling freak show.

Laura ran over and tried to brush the ants off my arms. "Just calm down buddy. It's okay," she said. Then the ants began attacking her. Her tone suddenly changed. "Get these goddamn things off of me!" she yelled.

"Just relax," said Darcy, moving her arms slowly. "It will be fiiiiiiiiine."

"Ahhhhhhhhh!," Laura yelled. We were both jumping up and down. Roberto seemed to have disappeared. He came back after a few minutes, hobbling quickly with a bucket in each hand. First he ran up to Laura, splashed her with thick, black sludge from the bucket. Then he doused me as well. He made a motion for us to slather the sludge all over ourselves. It felt like cigarettes were burning me and electric shocks were coursing across my skin. The sludge offered cool, moist, instant relief. The remaining ants began to depart from our arms, biting once or twice more to let us know what was what. After we cooled off and began to regain our composure, it was Darcy who noticed first.

"You guys smell like shit," she said.

"Shit? No, this is just mud. It's just mud," I repeated, trying to will the shit into just mud. But if it was mud, it was a very fecal smelling mud. Deep down inside my heart I knew it: it was shit. I was covered in shit. It was on my face, my arms, my chest, my legs. I was literally shit faced. So was Laura.

"I think she's right," I said to Laura. "We're covered in shit."

Laura began to cry, and her tears cleared small rivulets of peach colored skin in the vast field of poop on her face. "This sucks," she said. "I wish we were teachers."

The truck ride back down the mountain was mildly uncomfortable, more for our teacher friends than for us. Somehow we always seemed to have more people with us on the way down than on the way up. On that day there were ten or twelve. I was smooshed up against the red headed one. There was no water at the school to wash ourselves with. The school children pointed, more confused than amused. "So how was your lesson today?" I asked.

"Oh it was awful. One of them threw a book at me. We have forty kids that we're supposed to control. They can be such little shits sometimes-er, I mean..."

"It's okay," I said. "There are no secrets in the back of this truck."

"I know," she said, scrunching up her face a little.

We walked back to Blanca's and found two American girls sitting in the open courtyard that all the hotel rooms faced. They were putting on make-up. "Do I look too slutty?" one asked

"No," said the other. "Enrique will like that. All the women here put on too much make-up."

"What about Jorge?"

"I don't know, he said he was going out with Isabel tonight." She pouted. We sat down and read our Spanish-English dicionarios and they acted as though we were not there. "Do we have any coke left?"

"Enough for three or four lines." They looked young and sad to me, like girls trying to be women, playing dress up as adults.

I thought of asking one of them if they knew anything about shit gardening, but they didn't seem to be here for that. At least, that was not the vibe I got. We would see them come and go a few more times while we stayed with Blanca, each time looking progressively more strung out and desperate. Seeing people that had to be ten years younger than me looking strung out was hard to get my head around. Shouldn't I be closer to being a burnout than a couple of twenty-year-old girls?

As I sat lounging in the courtyard listening to the American girls talk about their coke and boyfriend supplies, Blanca came up to me. "Julio," she said and wrinkled her nose. I caught, "barn," and "cow" and "oh my." I raised my shoulders sheepishly and tried to use mime to communicate how ants bit me and shit was thrown on me. I made a pinching gesture with my thumb and forefinger on my arms and made a sound like, "Dah! Dah, dah, dah!" Blanca rolled her eyes and smiled. She must have smelled us before we came in. She started wiping down my face like a child. "Julio, pobrecito! What has happened? Did you fall in a toilet?"

"No Blanca, I don't know. It is bad today, very bad." That was all I knew how to say. Then she made cooing, motherly noises and then she started talking about how Jesus and the blood of Jesus is the answer to everything. I could understand "blood," and "Christ" and "virgin." Down here in these parts, they often referred to Jesus as El Señor Arriba-the Big Mr. Up Above. After we cleaned up, Blanca fed us twenty pounds of food, massive plates of rice and beans and homemade tortillas and four and five whole hard boiled eggs apiece. She clearly thought the gringos in her midst were starving to death, especially if we were skinnier than the folks here but came from a country one hundred times as rich. She invited us to go to church with her, and we said we'd think about it. Blanca was Pentecostal and I explained to Darcy and Laura that this meant speaking in tongues and a lot of crying and yelling and singing and we might get singled out for some extra attention, being foreigners, unsaved, unwashed and ignorant.

Instead of church we ambled into the zocalo and bought beer while watching itinerant hippies juggle burning torches while dropping them on the ground. A crowd was gathered and a bunch of loose babies were trying to pick one up off the ground. The torch dropped again and a pregnant, three legged dog ambled up and licked at the torch. It uttered a strangled, "urp!" as its tongue got singed. The people laughed. The children wanted to see it again. After about ten more minutes of dropping torches, the crowd dispersed and the dogs and babies followed behind snuffing and pawing at the trails of discarded, half-eaten kabobs, tortillas and corn in foil wrappers. The hippies walked around collecting coins from people, and Darcy looked at their chests with her mouth open.

We walked to a liquor store and bought some overpriced, crappy Honduran beer. We returned to the zocalo and started working on it immediately, for the minute it turned warm we would not be able to keep drinking. A homeless man in a ripped shirt and pants came up to us. He appeared to have splotches of dried vomit all over his shirt. His dirty feet were unclad. "Womens!" he said, by way of greeting. "You girls want cocaína? Horsey rides? Cheap, cheap, cheap!" We said no and he continued to pester us. Soon, he was joined by a one-eyed dwarf who wanted to show me where he had the cocaine and the horses.

"Both together?"

"Si, señor. And if you no like your womans, I have womans. Very young and cheap!"

"I'm more interested in the cocaine," I said.

Laura looked at me in disbelief. "What the hell are you talking about? If you buy that shit we'll all go to prison."

"I just want to try it once. Nobody cares around here."

The dwarf jumped up excited. He leaned toward me, his one eye popping out. "Once yes! One time good! You try once! Try one time, solamente! But if you like, maybe try again?"

"Okay, I understand. Thank you. I'll find you later."

"You no want to see the horses and the cocaína now?"

"No, later."

"Later. Okay, later good." He smiled lasciviously and winked, but since he could only wink with one eye, it looked ridiculous to me. He finally seemed to get it. "Okay, how about now? My village is very close. We take cocaína, ride horseys back here. You see the womans too."

"I already have womans," I said. "Really now, we have to go. We have very important business."

"And what is that?"

"Business," I said.

Laura was pulling my arm. "What are you doing? Leave this turd here. Let's just go. Come on."

Meanwhile, the shoeless guy was propositioning Darcy. Along with the usual horses and cocaína, he also said, "Sexo, conmigo?" He pointed to himself, then to Darcy, then he made his thumb and forefinger into a circle and made a crude in-out/in-out gesture while laughing maniacally. I silently wondered if he was a glue sniffing causality. He seemed utterly deranged. Darcy responded to these courtship gestures by waving her arms slowly. "No thannnnks," she said. "No sexo with you! I'm fiiiiiine." The man kept giggling and making the in-out gesture. The dwarf was tugging on my shirt sleeve while Laura was dragging me away.

"Señor? Señor? I must please ask you something? About cocaína?"

"Come! On!" said Laura, and my feet started moving.

"Well, guys this has been very intellectually stimulating, but we have to go now."

They followed us through the center of a zocalo. Through one of the side arches I could see a group of elementary-school-aged children sharing a joint in the humid darkness. Behind the next arch, a man was pissing and taking a long pull off his beer simultaneously. The homeless guys saw another group of foreign females and began gravitating toward them and we continued down a side street, back to the hotel. I thought I heard the vomit-stained, barefoot dude ask, "Sexo?" as we rounded a corner. Then they were gone.

"I hope they get beaten," Laura said.

I felt bloated and mildly tipsy and we staggered back to the hotel in the dark, our flip-flops click-clacking on the flagstone streets that our guidebook had hailed as adding to the "colonial old-world charm" here. When we got inside the courtyard and closed the gate, we tried to tip-toe back to our rooms, but our sneaky footsteps were interrupted by low but pronounced weeping coming from around the corner: it was Blanca. Our mom was crying. "Should we go and find out what's wrong?" Darcy whispered.

"Maybe just one of us should," I said. "I'll go." I tip-toed around the corner as the girls went off to bed and found poor Blanca with her head in her hands. I got down on my knees and she put her hand on my arm.

"Julio," she said. "You're a good boy, even though you have La Marca."

"La Marca?"

"Si!" she said, and pointed to the buffalo skull tattoo on my left upper forearm. "The Big Mr. Above, he doesn't like it."

"I'm sorry. I did not intend the bad thing," was about all I could muster.

Blanca laughed, as though amused by the antics of an innocent child or a village idiot. To her I think I may have seemed like a basically good egg who did not know any better about these things. "You have bigger problems," she said patting me on the shoulder. "You have many girlfriends with many babies, don't you Julio?" she was teasing me, but there was a look of utter despair in her eyes.

"What's bad with you?" I asked

"My children don't believe. My husband hits me. He also does not believe." It was a lot to take in. She was a lonely Evangelical Christian whose family didn't share her beliefs, whose husband beat her, whose supermom kindness to dirty gringos was not repaid by going to church with her, but by going to the zocalo to drink with homeless men peddling horses and cocaine. A wave of sympathy and shame came over me. I never imagined I would ever feel anything like compassion toward a fundamentalist Christian. Here was one before me who lived her beliefs, who was filled with nothing but nurture, kindness and goodwill for everybody. Somebody who fed us twenty times a day, killed spiders in our room at three in the morning, and did our laundry and folded our clothes. No one had ever done my laundry for me since I was ten.

I patted Blanca on the shoulder, then leaned over to hug her. "It's okay," I said. "Sorry, no church. Sorry, the beer. I know I bad man. You're good mom."

"Julio!" she said. "You're not bad. I wish you could come to be with the Big Mr. Above and me. That is why I'm sad."

"No more sad, Mama Blanca. Have happy. You good, good mom."

Blanca sighed, wiped her eyes and laughed. "Yes Julio, `supermom' that's me. You should learn Spanish Julio, and accept Mr. Jesus."

"Okay I try," I said, and Blanca laughed even harder.

One week later we were high in the mountains again. Roberto's plot was only fifty by fifty feet, but we had cleared and terraced the land. We were ready to plant cilantro, cucumbers and tomatoes. We began dropping seeds in the ground, when Roberto stopped us. "One more thing we need to do," he said. He trotted back to the doorless outhouse and came back with a bucket. He emptied the bucket with a plop in the middle of the field as we stood with our mouths open. Then he went back four more times. He waved his arms around, indicating we should spread the buckets of human feces around in the field.

I wanted to tell him: you saw me dig out the stump. I never complained, not even about the fire ants. You laughed while we dug. We're not lazy gringos, but we don't dig in shit.

"For real?" Darcy said. "No waaaaaay! I almost gagged when I smelled you guys last time."

"This is sick," said Laura. "I can't do this anymore. I'll puke."

"How do we say `dig', guys?" I asked. "How do we say, `no dig in shit'?"

Nobody knew. Our phrasebooks were not able to anticipate this reality. The chapter entitled "At the Market" came closest, but it only covered purchasing produce, not fecal gardening. All I could say was, "No shit, Roberto. Sorry."

Roberto looked confused. He shrugged his shoulders. "Aqui y aqui," he said, pointing at the shit. He made a shoveling motion. "Everywhere shit," he said. "See?"

I folded my arms, "No." Roberto cast me an annoyed glance. "You no understand, sir," I said. "No shit. No shit for us."

Roberto rubbed his chin thoughtfully and looked up at the sky. It was slowly dawning on him that it was not a lack of feces for gardening that we were lamenting, but rather that the gringos did not want to garden with it. Suddenly he threw up his arms in exasperation.

"Why not!" he said.

"Dirty. Sick. Yuck," was our answer.

"You are not farmers at all!" he spat. "Muy delicado! So sensitive! Ptuh! I knew it all along! Lazy dogs!"

We took this as our thanks and goodbye. With the better part of a day left to go, we picked up our tools and hiked a mile back down the mountain toward the schoolhouse. The British women saw us and waved. "Ding dong! You Yanks don't smell funny today."

We told them what had happened, and they expressed sympathy that Roberto was angry. "Well, we never promised him a shit garden," I said.

Justin Teerlinck is a raconteur, confidence man, trickster and Third World adventurer. He currently resides in a bungalow in St. Paul, where he writes restroom reviews for restroomratings.com.